28 DIY Uses for Old Wood Palettes

Companies often throw out old wooden palettes and other similar materials. If you take the time to find a good source for them, you can build all kinds of amazing things yourself. Not only can you build rugged outdoor furniture that will last a lifetime, you can give it some extra finishing and make some …

How One Commitment Can Change Your Life

Welcome to The Academy Full disclosure- I didn’t join Superhero Academy through the normal means. The instructor, Marc Angelo Coppola, held my interest for other reasons, but I’ll get into those later. Regardless, now that I’m in it, I wouldn’t have changed this part of my life for any other option. Ultimately, what got me …

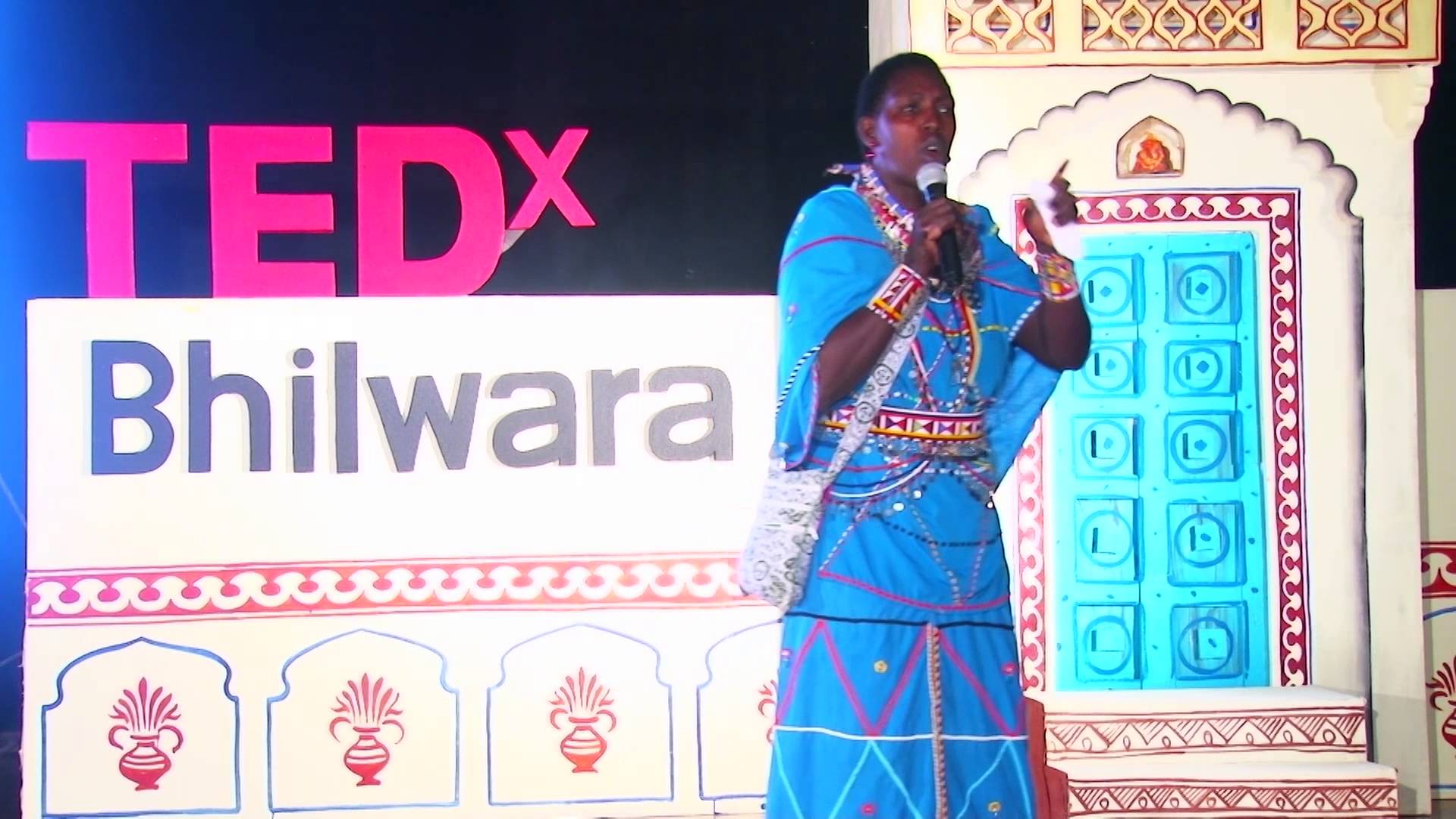

Can A Grandmother From A Hunter Gathering Tribe Become A Solar Engineer?

We’re all looking for stories of hope – that the world can be changed, that we are not limited by our culture, our backgrounds, our histories – and few stories are as inspirational as that of Lucy Naipanoi, a grandmother of Maasai, one of the last hunter gatherer tribes left on the planet. With the …

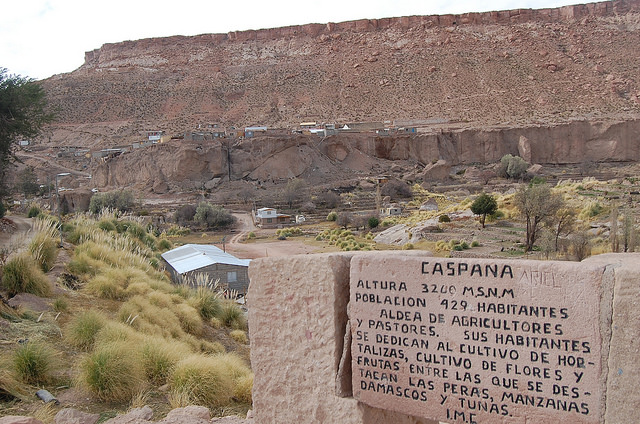

Two Indigenous Solar Engineers Changed Their Village in Chile

Liliana and Luisa Terán, two indigenous women from northern Chile who travelled to India for training in installing solar panels, have not only changed their own future but that of Caspana, their remote village nestled in a stunning valley in the Atacama desert.

“It was hard for people to accept what we learned in India,” Liliana Terán told IPS. “At first they rejected it, because we’re women. But they gradually got excited about, and now they respect us.”

Her cousin, Luisa, said that before they travelled to Asia, there were more than 200 people interested in solar energy in the village. But when they found out that it was Liliana and Luisa who would install and maintain the solar panels and batteries, the list of people plunged to 30.

“In this village there is a council of elders that makes the decisions. It’s a group which I will never belong to,” said Luisa, with a sigh that reflected that her decision to never join them guarantees her freedom.

Luisa, 43, practices sports and is a single mother of an adopted daughter. She has a small farm and is a craftswoman, making replicas of rock paintings. After graduating from secondary school in Calama, the capital of the municipality, 85 km from her village, she took several courses, including a few in pedagogy.

Liliana, 45, is a married mother of four and a grandmother of four. She works on her family farm and cleans the village shelter. She also completed secondary school and has taken courses on tourism because she believes it is an activity complementary to agriculture that will help stanch the exodus of people from the village.

But these soft-spoken indigenous women with skin weathered from the desert sun and a life of sacrifice are in charge of giving Caspana at least part of the energy autonomy that the village needs in order to survive.

Caspana – meaning “children of the hollow” in the Kunza tongue, which disappeared in the late 19th century – is located 3,300 metres above sea level in the El Alto Loa valley. It officially has 400 inhabitants, although only 150 of them are here all week, while the others return on the weekends, Luisa explained.

They belong to the Atacameño people, also known as Atacama, Kunza or Apatama, who today live in northern Chile and northwest Argentina.

“Every year, around 10 families leave Caspana, mainly so their children can study or so that young people can get jobs,” she said.

Up to 2013, the village only had one electric generator that gave each household two and a half hours of power in the evening. When the generator broke down, a frequent occurrence, the village went dark.

Today the generator is only a back-up system for the 127 houses that have an autonomous supply of three hours a day of electricity, thanks to the solar panels installed by the two cousins.

Each home has a 12 volt solar panel, a 12 volt battery, a four amp LED lamp, and an eight amp control box.

The equipment was donated in March 2013 by the Italian company Enel Green Power. It was also responsible, along with the National Women’s Service (SERNAM) and the Energy Ministry’s regional office, for the training received by the two women at the Barefoot College in India.

On its website, the Barefoot College describes itself as “a non-governmental organisation that has been providing basic services and solutions to problems in rural communities for more than 40 years, with the objective of making them self-sufficient and sustainable.”

So far, 700 women from 49 countries of Asia, Africa and Latin America – as well as thousands of women from India – have taken the course to become “Barefoot solar engineers”.

They are responsible for the installation, repair and maintenance of solar panels in their villages for a minimum of five years. Another task they assume is to open a rural electronics workshop, where they keep the spare parts they need and make repairs, and which operates as a mini power plant with a potential of 320 watts per hour.

In March 2012 the two cousins travelled to the village of Tilonia in the northwest Indian state of Rajasthan, where the Barefoot College is located.

They did not go alone. Travelling with them were Elena Achú and Elvira Urrelo, who belong to the Quechua indigenous community, and Nicolasa Yufla, an Aymara Indian. They all live in other villages of the Atacama desert, in the northern Chilean region of Antofagasta.

“We saw an ad that said they were looking for women between the ages of 35 and 40 to receive training in India. I was really interested, but when they told me it was for six months, I hesitated. That was a long time to be away from my family!” Luisa said.

Encouraged by her sister, who took care of her daughter, she decided to undertake the journey, but without telling anyone what she was going to do.

The conditions they found in Tilonia were not what they had been led to expect, they said. They slept on thin mattresses on hard wooden beds, the bedrooms were full of bugs, they couldn’t heat water to wash themselves, and the food was completely different from what they were used to.

“I knew what I was getting into, but it took me three months anyway to adapt, mainly to the food and the intense heat,” she said.

She remembered, laughing, that she had stomach problems much of the time. “It was too much fried food,” she said. “I lost a lot of weight because for the entire six months I basically only ate rice.”

Looking at Liliana, she burst into laughter, saying “She also only ate rice, but she put on weight!”

Liliana said that when she got back to Chile her family welcomed her with an ‘asado’ (barbecue), ’empanadas’ (meat and vegetable patties or pies) and ‘sopaipillas’ (fried pockets of dough).

“But I only wanted to sit down and eat ‘cazuela’ (traditional stew made with meat, potatoes and pumpkin) and steak,” she said.

On their return, they both began to implement what they had learned. Charging a small sum of 45 dollars, they installed the solar panel kit in homes in the village, which are made of stone with mud roofs.

The community now pays them some 75 dollars each a month for maintenance, every two months, of the 127 panels that they have installed in the village.

“We take this seriously,” said Luisa. “For example, we asked Enel not to just give us the most basic materials, but to provide us with everything necessary for proper installation.”

“Some of the batteries were bad, more than 10 of them, and we asked them to change them. But they said no, that that was the extent of their involvement in this,” she said. The company made them sign a document stating that their working agreement was completed.

“So now there are over 40 homes waiting for solar power,” she added. “We wanted to increase the capacity of the batteries, so the panels could be used to power a refrigerator, for example. But the most urgent thing now is to install panels in the 40 homes that still need them.”

But, she said, there are people in this village who cannot afford to buy a solar kit, which means they will have to be donations.

Despite the challenges, they say they are happy, that they now know they play an important role in the village. And they say that despite the difficulties, and the extreme poverty they saw in India, they would do it again.

“I’m really satisfied and content, people appreciate us, they appreciate what we do,” said Liliana.

“Many of the elders had to see the first panel installed before they were convinced that this worked, that it can help us and that it was worth it. And today you can see the results: there’s a waiting list,” she added.

Luisa believes that she and her cousin have helped changed the way people see women in Caspana, because the “patriarchs” of the council of elders themselves have admitted that few men would have dared to travel so far to learn something to help the community. “We helped somewhat to boost respect for women,” she said.

And after seeing their work, the local government of Calama, the municipality of which Caspana forms a part, responded to their request for support in installing solar panels to provide public lighting, and now the basic public services, such as the health post, have solar energy.

“When I’m painting, sometimes a neighbour comes to sit with me. And after a while, they ask me about our trip. And I relive it, I tell them all about it. I know this experience will stay with me for the rest of my life,” said Luisa.

This reporting series was conceived in collaboration with Ecosocialist Horizons. Edited by Estrella Gutiérrez/Translated by Stephanie Wildes

Costa Rica Is Shutting Down All Zoos And Freeing Every Animal In Captivity

Costa Rica has announced that it will be the first country in the world to shut down its zoos and free the captive animals they hold. Costa Rica is an especially biodiverse country, holding about 4% of the world’s known species. Sadly, the country is contractually obligated to keep two of its zoos open for another decade. Still, after that, they plan to shut it down in favor of a cage-free habitat for the animals to live in.

Treehugger reports that the nation, which also recently banned hunting for sport, will close the last two zoos in the next 10 years and give the animals a more natural habitat in which to exist. They want to convey to the world that they respect and care for wild animals.

Environmental Minister René Castro says, “We are getting rid of the cages and reinforcing the idea of interacting with biodiversity in botanical parks in a natural way.”

We don’t want animals in captivity or enclosed in any way unless it is to rescue or save them.”

Any animals currently in captivity that would not survive in the wild will be cared for in rescue centers and wildlife sanctuaries. No new zoos will be opened.

Internet Connection In Amazon Will Connect Villagers to Environmentalists

The Valhalla Movement takes very seriously the sensitivity involved in “charity” and make a large effort to detect an organization’s altruism before participating. We have personally been introduced to ACT, a team that partners with indigenous folks to protect the Amazon Rainforest. Their members are effective change-makers in line with our mission and we vouch for them.

In August 2015, a groundbreaking event took place in the village of Ulupuene in the Brazilian Amazon: internet connectivity arrived.

Through a collaborative partnership between the Amazon Conservation Team (ACT), Associação Indígena Ulupuene (AIU), and the nonprofit Synbio Consultoria em Meio Ambiente, the Waurá indigenous people of Ulupuene now have access to the web and can reach like-minded communities and organizations around the world to enlist support for the protection of the community’s rainforests and ancestral lands. The project was fully funded by ACT.

Though installation planning commenced in 2013, the village’s remote location in the Xingu Indigenous Reserve protracted the process, with coordination of logistics with outside actors constituting the greatest source of delay.

Numerous providers were consulted, including those offering radio transmission-prohibitive because of the necessity of building a 60-meter radio tower-and government-provided service, for which a very lengthy waiting list exists. Ultimately, satellite-mediated internet was deemed most viable.

Because configuration and registration required preexisting phone and internet connections, the equipment was set up in the neighboring town of Canarana. After technical adjustments, the satellite antenna travelled 250 miles in Synbio’s truck to Ulupuene where the Waurá, in anticipation, had already built a traditional communal “office”. Several community members already owned tablets and smartphones and were eager to receive news from beyond the reserve.

Kumehin is now able to access the internet via her tablet.

Kumehin is now able to access the internet via her tablet.

Fittingly, upon inauguration, ACT co-founder Liliana Madrigal congratulated village chief Eleokar Waurá via the web, sending her best wishes to the community and emphasizing the many ways that the technology can be used for the benefit of the village and the protection of the forest. Eleokar thanked the partner institutions and expressed how the arrival of this tool had inspired his community.

Young Bloggers Become Guerrilla Gardening Gangsters

Guerrilla Gardening : The act of impromptu gardening in public spaces for the purpose of beautifying our community. /ɡəˈrilə ˈɡärd(ə)niNG / In this video stars our two phenomenal Web Developers and Coders, Greg and Jordan. The Shady character is Marty, our Networking Specialist and behind the cameras are Germ, Marc and yours truly. This video has been sleeping in …

By Asking One Simple Question, This Teen Saved A Man’s Life

Sometimes it’s the simplest and most humbling moments that matter most.

While it’s easy to get excited about innovative developments in technology, sometimes the simple things in life are what deserve applause and attention.

In the case of a teenager named Jamie Harrington, taking a moment to ask a man if he was okay was enough to prevent him from committing suicide.

As shared on the Humans of Dublin Facebook page, Harrington recalled his encounter one evening with a stranger who was sitting on a bridge:

“I was just on my way to the American sweet shop to buy some Gatorade, when I saw this guy in his 30s sitting on the ledge of the bridge,” Harrington says in his interview. “I stopped and asked him if he was okay … I pleaded with him for a while to come down and sit on the steps, and eventually he did.”

In a brilliant gesture of human kindness and empathy, Harrington talked to the man about his life and why he felt driven to commit suicide. The teen then insisted the man go to St. James Hospital, and called an ambulance. To ensure he could check up on the man later, Jamie also got the man’s number.

That’s not where the positive news ends, however.

“About three months ago, he texted me that his wife is pregnant, they’re having a boy, and they’re naming him after me,” Harrington said. “Can you believe that? They’re going to name their child after me … He said in that moment that I approached him, he was just about to jump, and those few words saved his life. That they’re still ringing in his head every day. ‘Are you okay?'”

This incredible news is hope for anyone in a down place, and inspiration for those seeking to make a difference in the world. Truly, all thoughts and actions matter.

Share this story and uplift someone else’s day. Comment your thoughts below.

The world is getting better all the time, in 11 maps and charts

by Zack Beauchamp on July 13, 2015

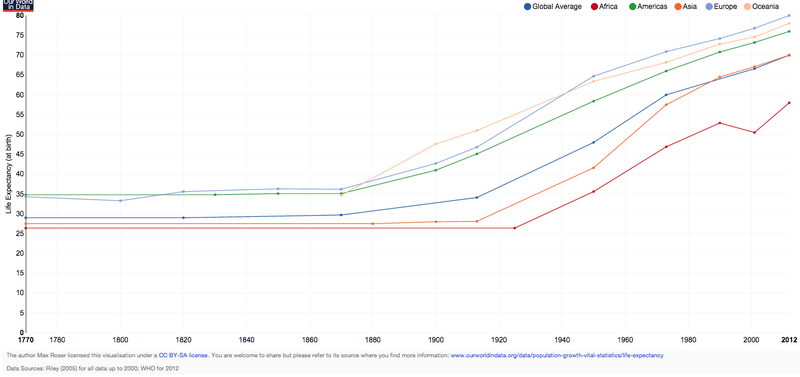

Reading the news, it sometimes feels like the world is falling apart: that everything is going to hell in a handbasket and we’re on the verge of a total collapse. In fact, we’re living through what is, by objective metrics, the best time in human history. People have never lived longer, better, safer, or richer lives than they do now. And these 11 charts and maps – which draw on centuries of data, as well as a brand new UN report that focuses on the past 25 years – prove it.

For most of human history, our lives were nasty, brutish, and pretty damn short. Only in the past 200 years or so, as this chart shows, have people started living lives that even come close to what we see as normal today. In 1770, the world’s average life expectancy was just 29 years old (a lot of people died really young). Today, it’s 70. That staggering jump represents the greatest accomplishment in human history: our victory over historical killers like disease, poverty, and war. Everything else in the post is, to a certain extent, an explanation of this one extraordinary fact.

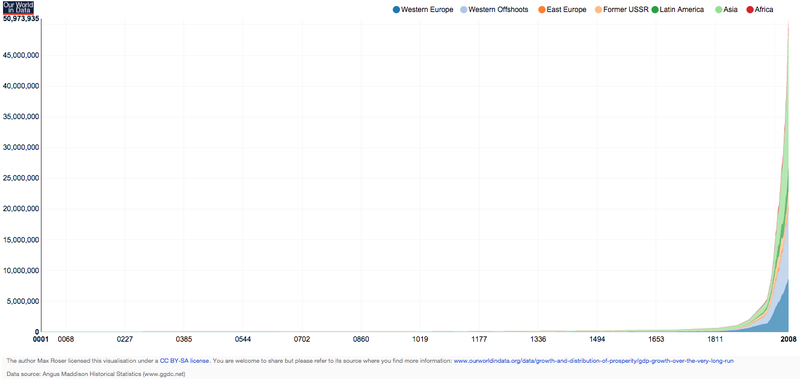

For most of human existence, our species was dirt poor. But that has changed rapidly since the 19th century: The world’s gross domestic product has spiked in a way that’s simply unprecedented in human history. The key factors here are the Scientific Revolution, the Enlightenment, the Industrial Revolution, and capitalism. These four transformations created and spread new ideas and technologies — modern medicine and electricity, for example — that allowed humanity to grow rich and healthy in a way that our distant ancestors simply couldn’t dream of.

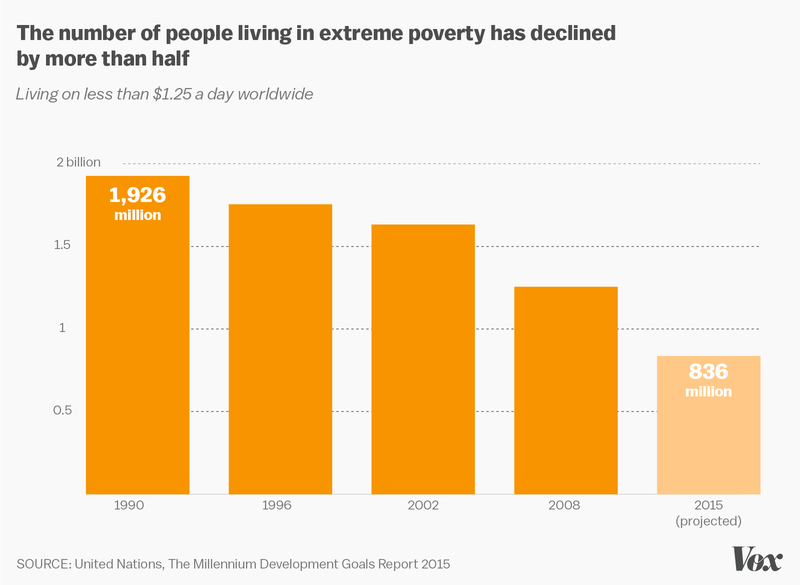

Economic growth hasn’t just benefited wealthy countries. Between 1990 and 2015, about 1.1 billion people have been lifted out of extreme poverty (defined as living on $1.25 a day). That means that in just the past 25 years, a full seventh of humanity has been saved from terrible want. A lot of that came from India and especially China, huge countries that experienced rapid growth in the past several decades. Much of sub-Saharan Africa is still mired in serious poverty. But the fact that the worldwide gains are concentrated in a few places doesn’t make them any less worthy of celebration. If what we care about is minimizing suffering in the world, then it shouldn’t matter what country the billion-plus people saved from poverty come from.

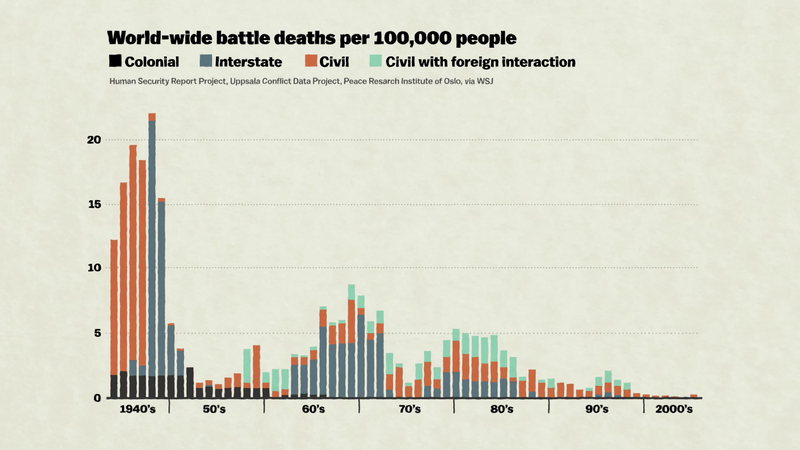

The modern world also birthed horrors — specifically, industrialized killing in the two world wars. But a wonderful thing has happened since then: Deaths from war have been in free fall. The percentage of the global population killed in wars has declined tremendously, owing in large part to the fact that major nuclear armed powers (like the US and Russia) have refrained from going to war. War isn’t over, obviously, but we’ve managed to contain it — safeguarding humanity’s gains from economic growth and scientific innovation.

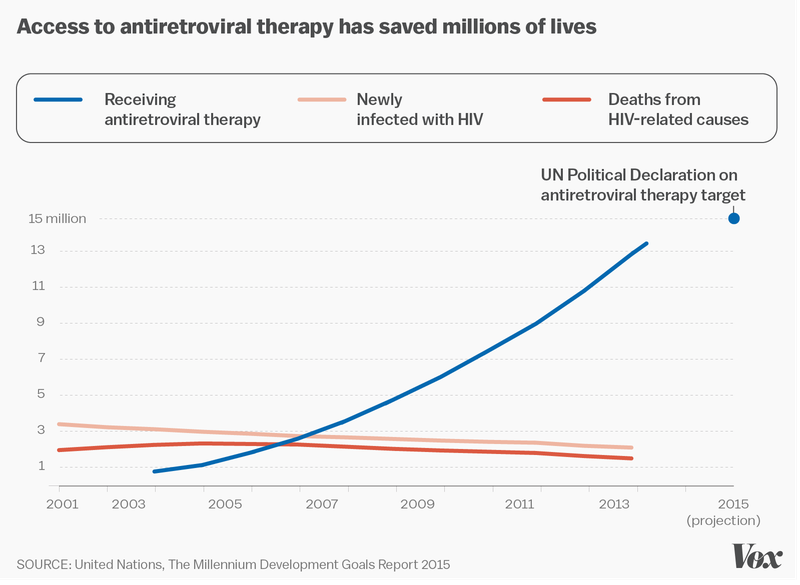

In the past 15 years, we’ve made serious progress in the fight against the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Between 2000 and 2013, documented new cases of HIV infection fell by 40 percent, and deaths from AIDS-related causes fell by 35 percent (from a peak in 2005). That’s in large part because there’s been a concerted global effort to spread the medication necessary to combat the plague. Programs like the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) have done an extraordinary job of getting impoverished people the treatment and assistance they need.

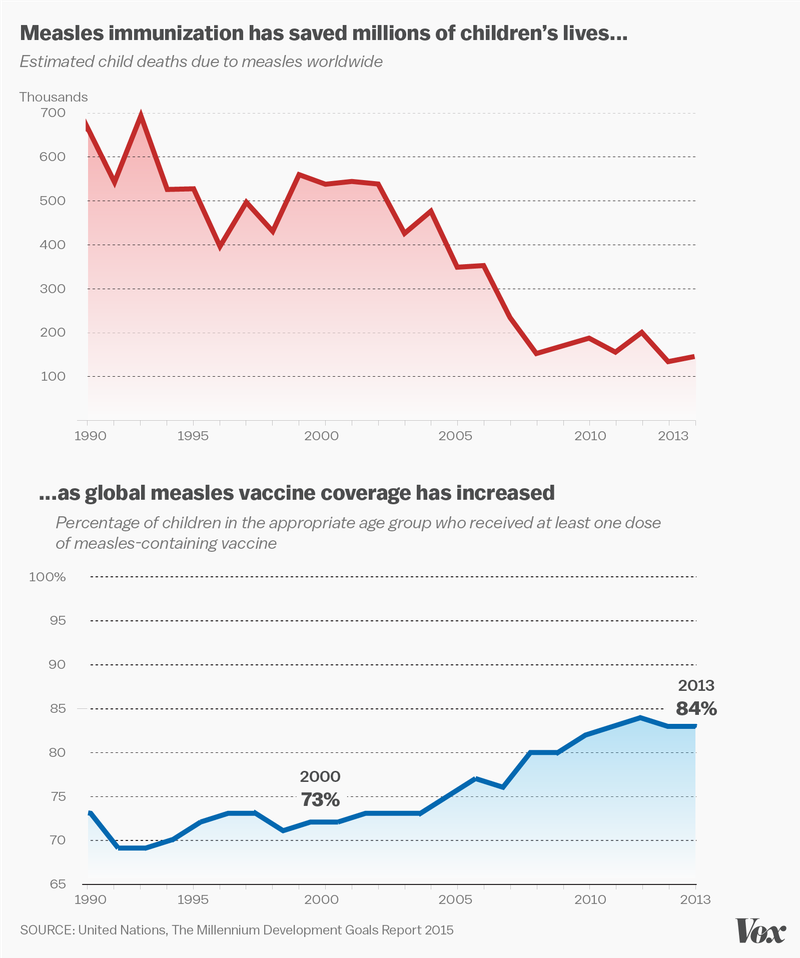

HIV/AIDS isn’t the only disease being beaten back. As the above chart shows, the global measles immunization campaign has been extraordinarily effective — saving the lives of an estimated 15.6 million people between 2000 and 2015. Deaths from malaria declined by 58 percent globally during the same period. Tuberculosis mortality has fallen by 43 percent since 1990. These diseases, all major killers in the developing world, are on the retreat — due to both local and international efforts to combat them.

The spread of democracy is a critical part of this whole story. The American and French Revolutions marked the beginning of its global rise, but it wasn’t until the Cold War ended that democracy became the most popular form of government on Earth. The ramifications of democracy’s spread have been enormous: Democratic governments have never (or almost never) gone to war with each other, and are significantly less likely to slaughter their own people. Democracy has also put pressure on political leaders to keep their citizens happy, helping spread the gains from economic growth and technology from the wealthy to most of the world’s population. And that’s to say nothing of democracy’s inherent benefits (like giving people the right to choose their own governments).

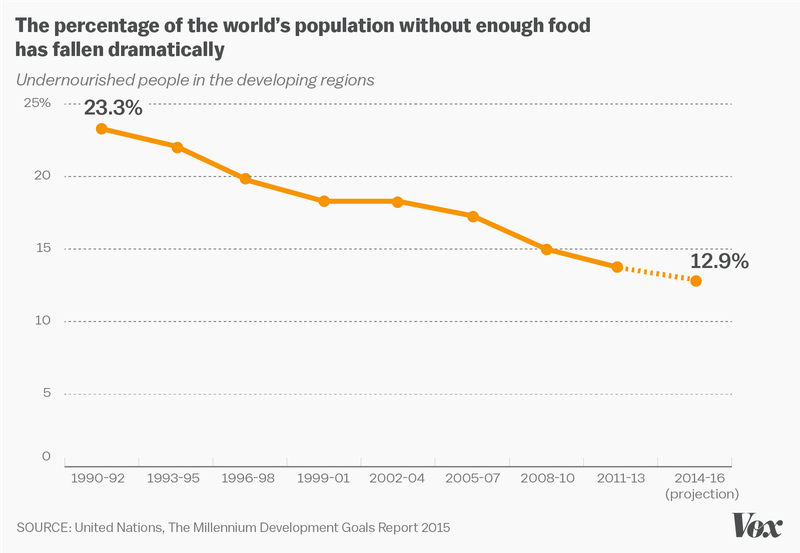

One of the benefits of the world’s growing wealth is that more people can afford food. From 1990 to 1992, 991 million people in the developing world were undernourished — meaning food-deprived — by the UN’s numbers. Today, that figure is 780 million. That’s a decline of more than 20 percent in the parts of the world where, in the past centuries, people have suffered the most from want of adequate food.

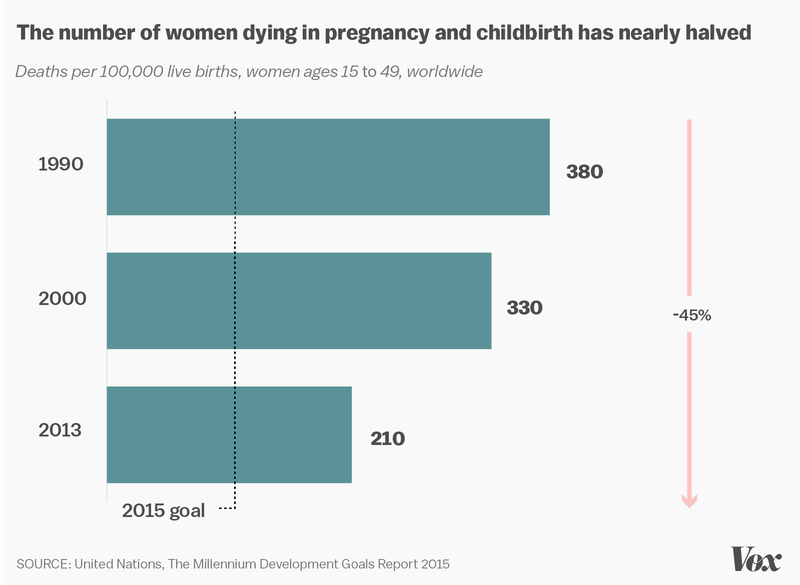

Until the advent of modern medicine, shocking percentages of women died in pregnancy and childbirth. The spread of techniques to address leading maternal killers, like hemorrhage and infection, has done wonders: Since 1990, the global rate of maternal mortality (death of a mother during pregnancy or within 42 days of its end) has gone down by a staggering 45 percent.

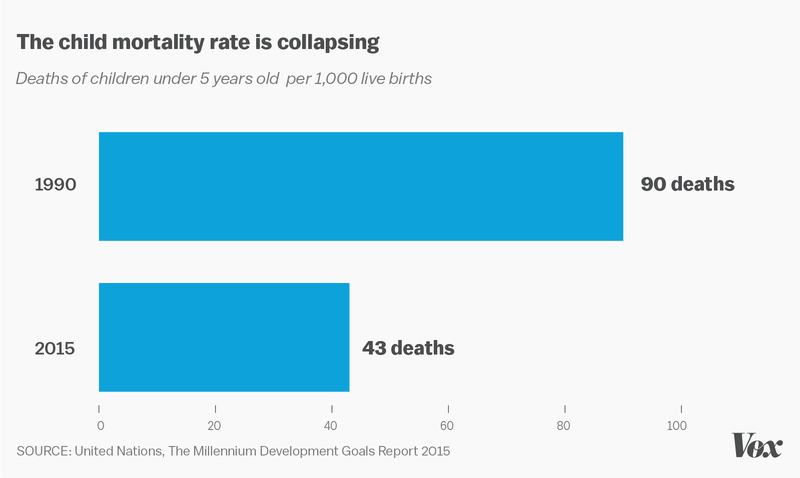

If you were born 400 years ago, the odds of you living past age 5 were terrifyingly low. Nowadays, the incidence of child mortality has plummeted, owing largely to improved access to health care and food. This is one of the key reasons life expectancy is so much higher than it used to be: The fewer deaths there are at a young age, the higher the average length of a human life from birth will be.

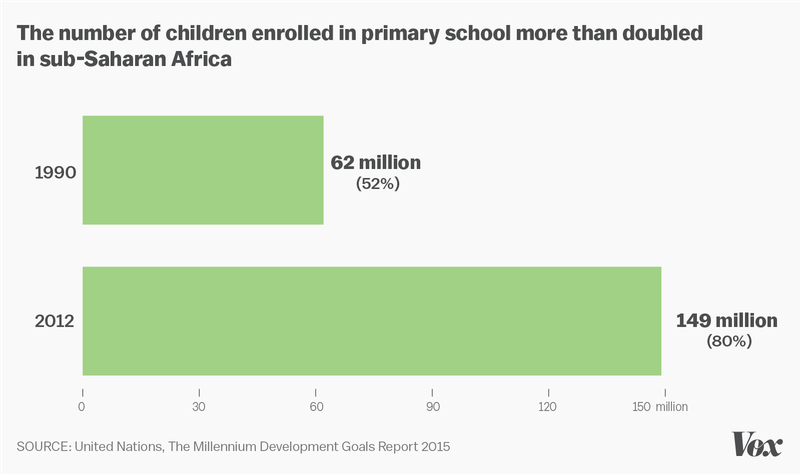

At the same time that more children are living to be old enough to get an education, opportunities for schooling have never been greater. Ninety-one percent of primary school-age kids worldwide are enrolled. Even in sub-Saharan Africa, the region with by far the worst primary school enrollment numbers, recent improvements have been nothing short of astonishing. In 1990, 52 percent of school-age kids in the region were enrolled. By 2012, that number had jumped to 80 percent.