by Zack Beauchamp on July 13, 2015

Reading the news, it sometimes feels like the world is falling apart: that everything is going to hell in a handbasket and we’re on the verge of a total collapse. In fact, we’re living through what is, by objective metrics, the best time in human history. People have never lived longer, better, safer, or richer lives than they do now. And these 11 charts and maps – which draw on centuries of data, as well as a brand new UN report that focuses on the past 25 years – prove it.

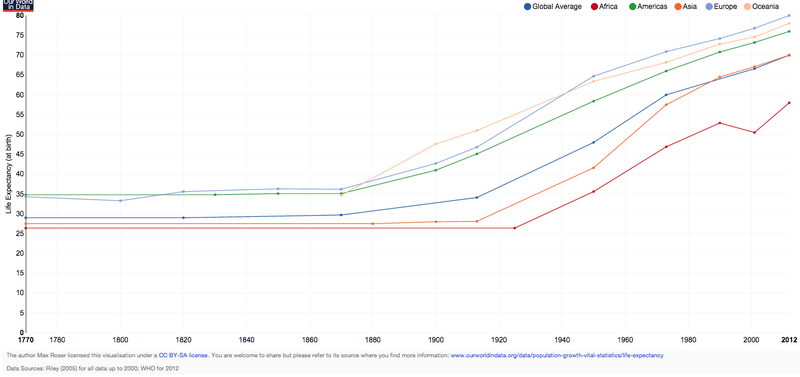

For most of human history, our lives were nasty, brutish, and pretty damn short. Only in the past 200 years or so, as this chart shows, have people started living lives that even come close to what we see as normal today. In 1770, the world’s average life expectancy was just 29 years old (a lot of people died really young). Today, it’s 70. That staggering jump represents the greatest accomplishment in human history: our victory over historical killers like disease, poverty, and war. Everything else in the post is, to a certain extent, an explanation of this one extraordinary fact.

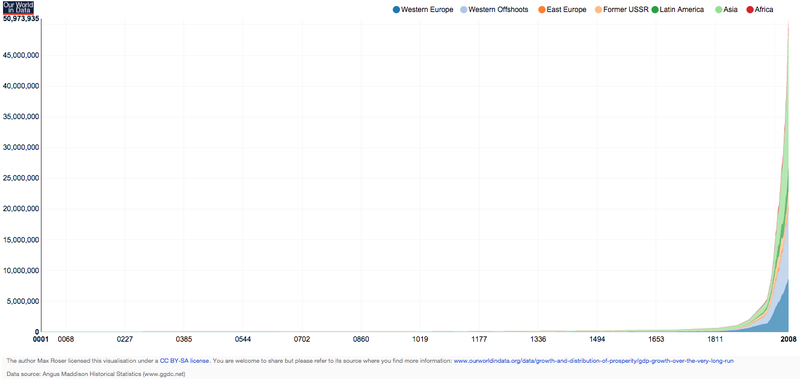

For most of human existence, our species was dirt poor. But that has changed rapidly since the 19th century: The world’s gross domestic product has spiked in a way that’s simply unprecedented in human history. The key factors here are the Scientific Revolution, the Enlightenment, the Industrial Revolution, and capitalism. These four transformations created and spread new ideas and technologies — modern medicine and electricity, for example — that allowed humanity to grow rich and healthy in a way that our distant ancestors simply couldn’t dream of.

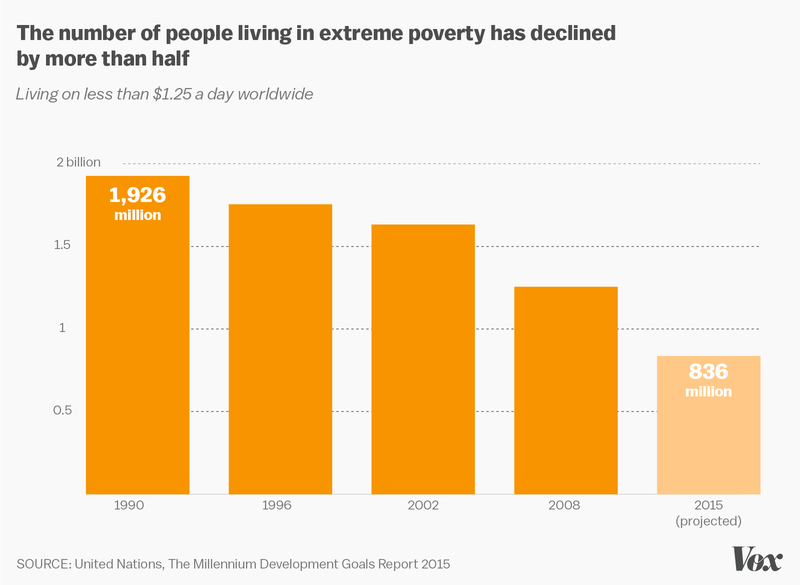

Economic growth hasn’t just benefited wealthy countries. Between 1990 and 2015, about 1.1 billion people have been lifted out of extreme poverty (defined as living on $1.25 a day). That means that in just the past 25 years, a full seventh of humanity has been saved from terrible want. A lot of that came from India and especially China, huge countries that experienced rapid growth in the past several decades. Much of sub-Saharan Africa is still mired in serious poverty. But the fact that the worldwide gains are concentrated in a few places doesn’t make them any less worthy of celebration. If what we care about is minimizing suffering in the world, then it shouldn’t matter what country the billion-plus people saved from poverty come from.

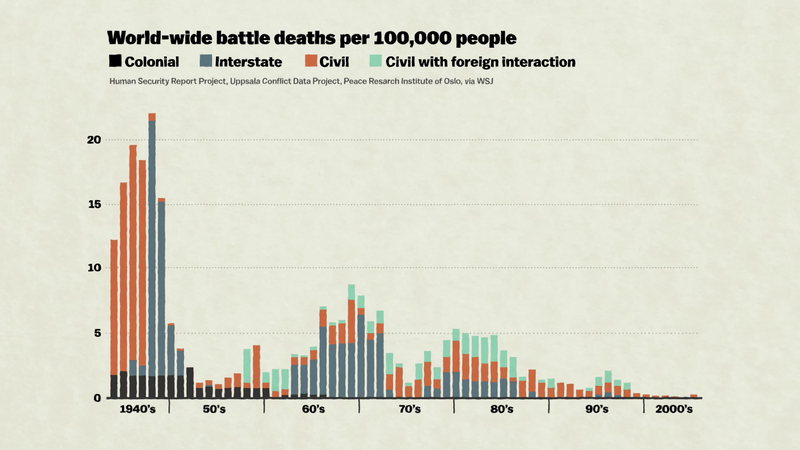

The modern world also birthed horrors — specifically, industrialized killing in the two world wars. But a wonderful thing has happened since then: Deaths from war have been in free fall. The percentage of the global population killed in wars has declined tremendously, owing in large part to the fact that major nuclear armed powers (like the US and Russia) have refrained from going to war. War isn’t over, obviously, but we’ve managed to contain it — safeguarding humanity’s gains from economic growth and scientific innovation.

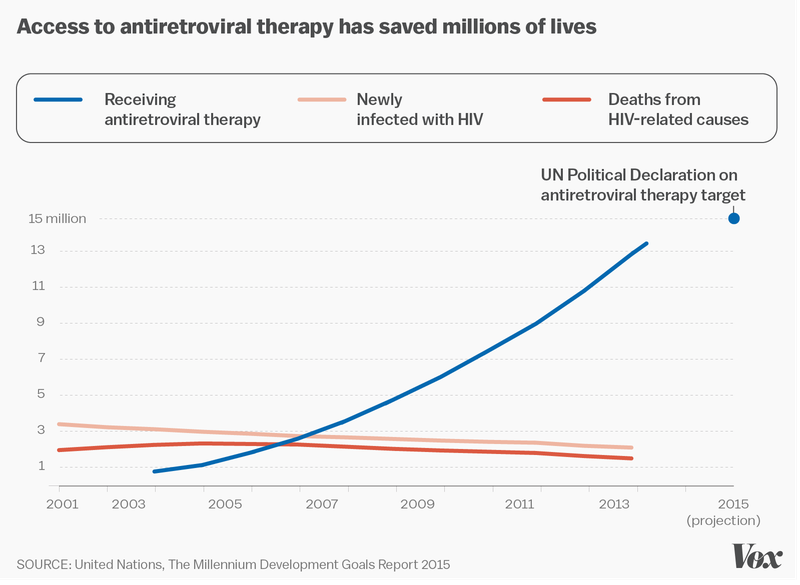

In the past 15 years, we’ve made serious progress in the fight against the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Between 2000 and 2013, documented new cases of HIV infection fell by 40 percent, and deaths from AIDS-related causes fell by 35 percent (from a peak in 2005). That’s in large part because there’s been a concerted global effort to spread the medication necessary to combat the plague. Programs like the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) have done an extraordinary job of getting impoverished people the treatment and assistance they need.

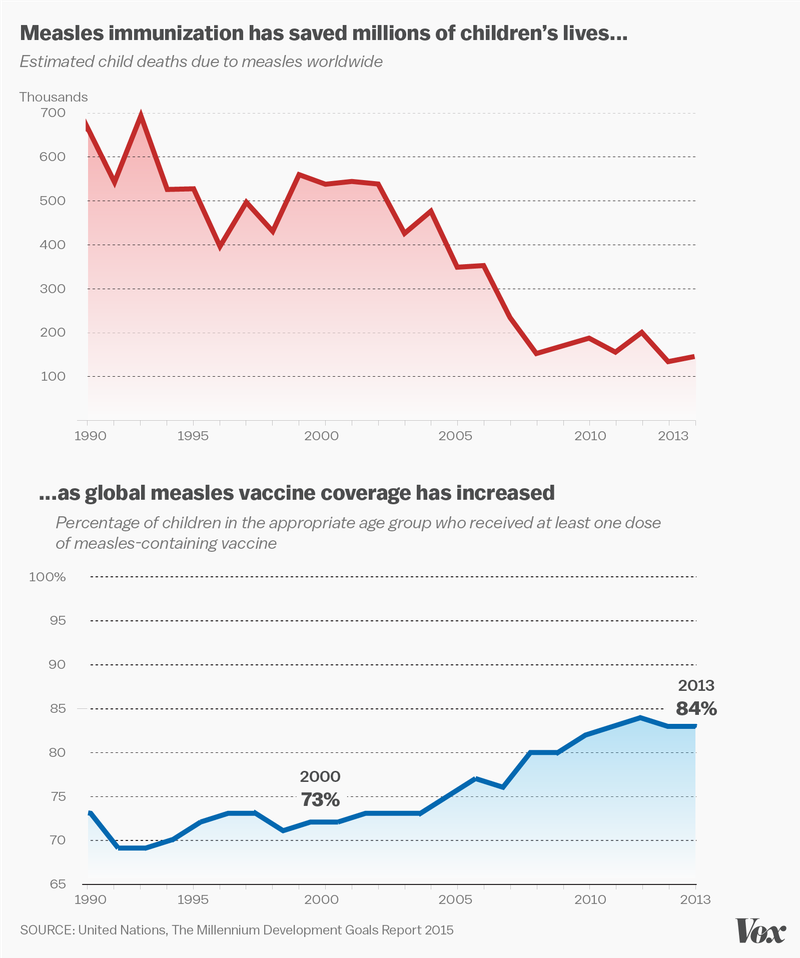

HIV/AIDS isn’t the only disease being beaten back. As the above chart shows, the global measles immunization campaign has been extraordinarily effective — saving the lives of an estimated 15.6 million people between 2000 and 2015. Deaths from malaria declined by 58 percent globally during the same period. Tuberculosis mortality has fallen by 43 percent since 1990. These diseases, all major killers in the developing world, are on the retreat — due to both local and international efforts to combat them.

The spread of democracy is a critical part of this whole story. The American and French Revolutions marked the beginning of its global rise, but it wasn’t until the Cold War ended that democracy became the most popular form of government on Earth. The ramifications of democracy’s spread have been enormous: Democratic governments have never (or almost never) gone to war with each other, and are significantly less likely to slaughter their own people. Democracy has also put pressure on political leaders to keep their citizens happy, helping spread the gains from economic growth and technology from the wealthy to most of the world’s population. And that’s to say nothing of democracy’s inherent benefits (like giving people the right to choose their own governments).

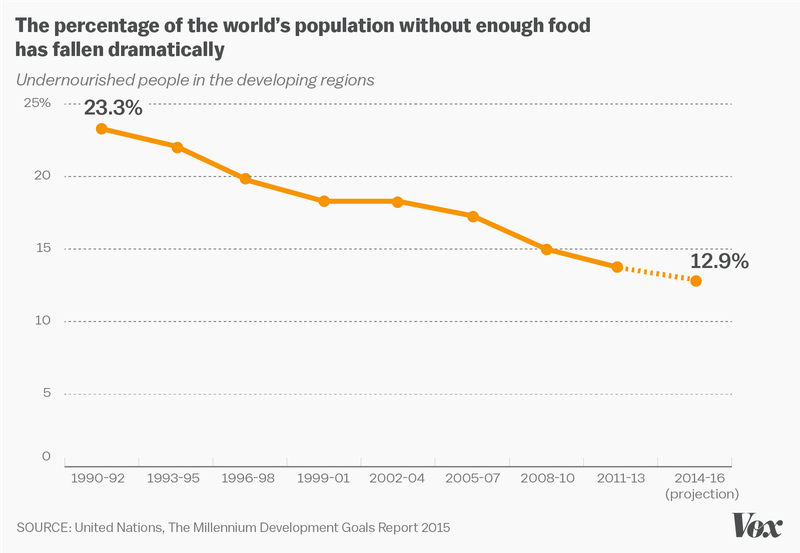

One of the benefits of the world’s growing wealth is that more people can afford food. From 1990 to 1992, 991 million people in the developing world were undernourished — meaning food-deprived — by the UN’s numbers. Today, that figure is 780 million. That’s a decline of more than 20 percent in the parts of the world where, in the past centuries, people have suffered the most from want of adequate food.

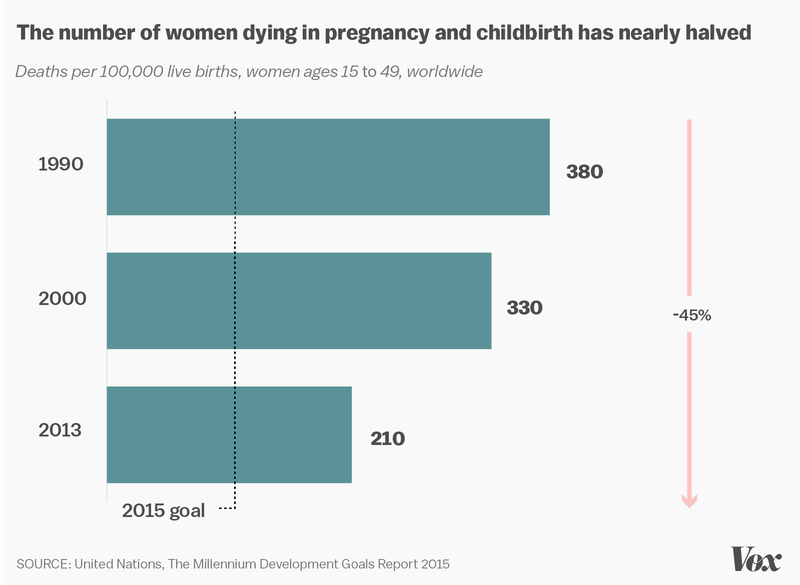

Until the advent of modern medicine, shocking percentages of women died in pregnancy and childbirth. The spread of techniques to address leading maternal killers, like hemorrhage and infection, has done wonders: Since 1990, the global rate of maternal mortality (death of a mother during pregnancy or within 42 days of its end) has gone down by a staggering 45 percent.

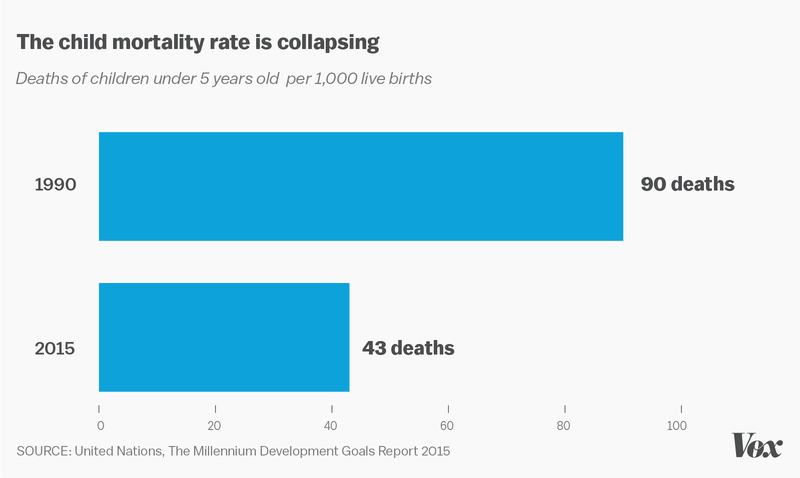

If you were born 400 years ago, the odds of you living past age 5 were terrifyingly low. Nowadays, the incidence of child mortality has plummeted, owing largely to improved access to health care and food. This is one of the key reasons life expectancy is so much higher than it used to be: The fewer deaths there are at a young age, the higher the average length of a human life from birth will be.

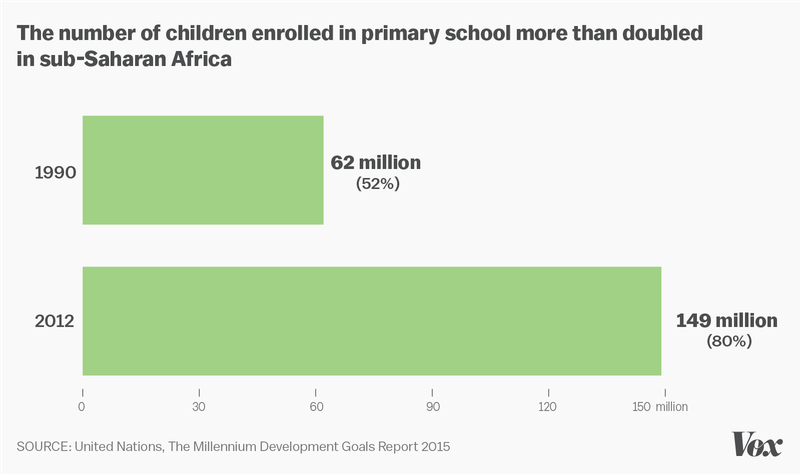

At the same time that more children are living to be old enough to get an education, opportunities for schooling have never been greater. Ninety-one percent of primary school-age kids worldwide are enrolled. Even in sub-Saharan Africa, the region with by far the worst primary school enrollment numbers, recent improvements have been nothing short of astonishing. In 1990, 52 percent of school-age kids in the region were enrolled. By 2012, that number had jumped to 80 percent.