Why aren’t more cities using it?

By Scott Carrier | Tuesday Feb. 17, 2015 06:00 AM | Photos by Jim McAuley

By Scott Carrier | Tuesday Feb. 17, 2015 06:00 AM | Photos by Jim McAuley

It’s early December, 10:30 in the morning, and Rene Zepeda is driving a Volunteers of America minivan around Salt Lake City, looking for reclusive homeless people, those camping out next to the railroad tracks or down by the river or up in the foothills. The winter has been unseasonably warm so far-it’s 60 degrees today-but the cold weather is coming and the van is stacked with sleeping bags, warm coats, thermal underwear, socks, boots, hats, hand warmers, protein bars, nutrition drinks, canned goods. By the end of the day, Rene says, it will all be gone.

These supplies make life a little easier for people who live outside, but Rene’s main goal is to develop a relationship of trust with them, and act as a bridge to get them off the street. “I want to get them into homes,” Rene says. “I tell them, ‘I’m working for you. I want to get you out of the homeless situation.'”

And he does. He and all the other people who work with the homeless here have perhaps the best track record in the country. In the past nine years, Utah has decreased the number of homeless by 72 percent-largely by finding and building apartments where they can live, permanently, with no strings attached. It’s a program, or more accurately a philosophy, called Housing First.

One of the two phones on the dash starts ringing. “Outreach, this is Rene.” He’s upbeat, the voice you want to hear if you’re in trouble. “Do you want to meet at the motel? Or the 7-Eleven?” he asks. “Okay, we’ll be there in five minutes.”

Five days ago, William Miller, 63, was diagnosed with liver cancer at St. Mary’s Hospital in Reno, Nevada. The next day a friend put him on the train to Salt Lake City, hoping the Latter Day Saints Hospital might help. For the past two nights he’s been sleeping under a freeway viaduct. He vomits when he wakes up in the morning and has gone through two sets of clothes due to diarrhea. Yesterday he went to the LDS Hospital for a checkup and slept for five and a half hours in a bathroom. Now he’s sitting on the back of the van in a motel parking lot. A friend staying at the motel let him take a shower in his room, but then William started feeling weak, so he called Rene.

“I’m one that rarely gets sick,” he says. “It takes a lot to get me down, but I’m all out of everything.”

He has bushy sideburns and a lot of hair sticking out from a beanie and looks as if he was once much bigger than he is now, like he’s shrinking inside oversized clothes.

“I had two cups of Jell-O yesterday. My buddy got me a cup of coffee and a couple of doughnuts, but I’m gagging and throwing up everything. I’m nodding out talking to people, and that’s not good.”

Rene helps William get in the passenger seat and drives him to the Fourth Street Clinic, which provides free care for the homeless and is where Rene used to work as an AmeriCorps volunteer. He knows the system and trusts the doctors and nurses. William gets out of the van and walks inside very slowly and sits down in the waiting room. Rene checks him in. “I’m a tough old bird,” William says to me. “I ain’t never had something like this. I’m just weak as all get out, and in a lot of pain.”

Then he nods off.

The next stop is at a camp next to the railroad tracks. A 57-year-old man and a 41-year-old woman are living in a three-man dome tent covered with plastic tarps. Patrick says he’s doing okay, even though he’s had two strokes this year and has two tumors on his left lung and walks with a cane.

“My legs are going out. I’m sure it’s from camping out. We were living in the hills for two years,” he says. “My girlfriend, Charmaine, is talking about killing herself she’s in so much pain.” Charmaine is a heroin addict who suffers from diabetes, grand mal seizures, cirrhosis, and heart attacks. “When we lived in the foothills we both got bit by poisonous spiders,” she says, showing me a three-inch scar above her swollen right ankle. “The doctor tried to cut out the infection, but he accidently cut my calf muscle.”

She walks slowly, with a limp. As Rene is getting Charmaine in the van, Patrick takes him aside and asks if maybe Rene could get her into one of the subsidized apartments for chronically homeless people.

“If she comes back here she’ll die,” he says. “Especially with the cold weather coming.”

Rene tells him he’ll look into it.

On the way to the Fourth Street Clinic, I ask Charmaine how many times she’s been to an emergency room or clinic this year.

“More times than I can count,” she says.

By the end of the day, Rene has met with 12 homeless people, all with drug and alcohol problems, many requiring medical help, all needing the sleeping bags, warm clothes, food, and supplies that he hands out. As the sun sets we head back to the office with an empty van.

“I do it for the money and glamour,” he says, laughing. “No, I mean you cross a line and you really can’t go back, ’cause you just know this is out here.”

We could, as a country, look at the root causes of homelessness and try to fix them. One of the main causes is that a lot of people can’t afford a place to live. They don’t have enough money to pay rent, even for the cheapest dives available. Prices are rising, inventory is extremely tight, and the upshot is, as a new report by the Urban Institute finds, that there’s only 29 affordable units available for every 100 extremely low-income households.So we could create more jobs, redistribute the wealth, improve education, socialize health carebasically redesign our political and economic systems to make sure everybody can afford a roof over their heads.

Instead of this, we do one of two things: We stick our heads in the sand or try to find bandages for the symptoms. This story is about how Utah has found a third way.

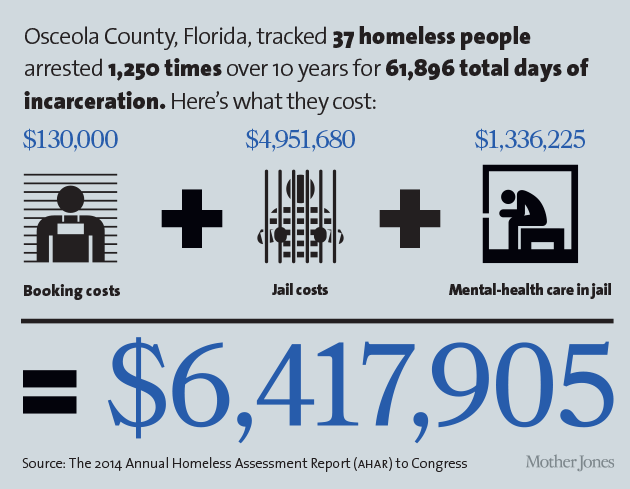

To understand how the state did that it helps to know that homeless-service advocates roughly divide their clients into two groups: those who will be homeless for only a few weeks or a couple of months, and those who are “chronically homeless,” meaning they have been without a place to live for more than a year, and have other problems-mental illness or substance abuse or other debilitating damage. The vast majority, 85 percent, of the nation’s estimated 580,000 homeless are of the temporary variety, mainly men but also women and whole families who spend relatively short periods of time sleeping in shelters or cars, then get their lives together and, despite an economy increasingly stacked against them, find a place to live, somehow. However, the remaining 15 percent, the chronically homeless, fill up the shelters night after night and spend a lot of time in emergency rooms and jails. This is expensive-costing between $30,000 and $50,000 per person per year according to the Interagency Council on Homelessness. And there are a few people in every city, like Reno’s infamous “Million-Dollar Murray,” who really bust the bank. So in recent years, both local and federal efforts to solve the homelessness epidemic have concentrated on the chronic population, currently about 84,000 nationwide.

In 2005, approximately 2,000 of these chronically homeless people lived in the state of Utah, mainly in and around Salt Lake City. Many different agencies and groups-governmental and nonprofit, charitable and religious-worked to get them back on their feet and off the streets. But the numbers and costs just kept going up.

The model for dealing with the chronically homeless at that time, both here and in most places across the nation, was to get them “ready” for housing by guiding them through drug rehabilitation programs or mental-health counseling, or both. If and when they stopped drinking or doing drugs or acting crazy, they were given heavily subsidized housing on the condition that they stay clean and relatively sane. This model, sometimes called “linear residential treatment” or “continuum of care,” seemed to be a good idea, but it didn’t work very well because relatively few chronically homeless people ever completed the work required to become “ready,” and those who did often could not stay clean or stop having mental episodes, so they lost their apartments and became homeless again.

In 1992, a psychologist at New York University named Sam Tsemberis decided to test a new model. His idea was to just give the chronically homeless a place to live, on a permanent basis, without making them pass any tests or attend any programs or fill out any forms.

“Okay,” Tsemberis recalls thinking, “they’re schizophrenic, alcoholic, traumatized, brain damaged. What if we don’t make them pass any tests or fill out any forms? They aren’t any good at that stuff. Inability to pass tests and fill out forms was a large part of how they ended up homeless in the first place. Why not just give them a place to live and offer them free counseling and therapy, health care, and let them decide if they want to participate? Why not treat chronically homeless people as human beings and members of our community who have a basic right to housing and health care?”

Tsemberis and his associates, a group called Pathways to Housing, ran a large test in which they provided apartments to 242 chronically homeless individuals, no questions asked. In their apartments they could drink, take drugs, and suffer mental breakdowns, as long as they didn’t hurt anyone or bother their neighbors. If they needed and wanted to go to rehab or detox, these services were provided. If they needed and wanted medical care, it was also provided. But it was up to the client to decide what services and care to participate in.

The results were remarkable. After five years, 88 percent of the clients were still in their apartments, and the cost of caring for them in their own homes was a little less than what it would have cost to take care of them on the street. A subsequent study of 4,679 New York City homeless with severe mental illness found that each cost an average of $40,449 a year in emergency room, shelter, and other expenses to the system, and that getting those individuals in supportive housing saved an average of $16,282. Soon other cities such as Seattle and Portland, Maine, as well as states like Rhode Island and Illinois, ran their own tests with similar results. Denver found that emergency-service costs alone went down 73 percent for people put in Housing First, for a savings of $31,545 per person; detox visits went down 82 percent, for an additional savings of $8,732. By 2003, Housing First had been embraced by the Bush administration.

Still, the new paradigm was slow to catch on. Old practices are sometimes hard to give up, even when they don’t work. When Housing First was initially proposed in Salt Lake City, some homeless advocates thought the new model would be a disaster. Also, it would be hard to sell the ultra-conservative Utah Legislature on giving free homes to drug addicts and alcoholics. And the Legislature would have to back the idea because even though most of the funding for new construction would come from the federal government, the state would have to pick up the balance and find ways to plan, build, and manage the new units. And where are you going to put them? Not in my backyard.

This is when two men who’d worked with the homeless in Utah for many years-Matt Minkevitch, executive director of the largest shelter in Salt Lake City, and Kerry Bate, executive director of the Housing Authority of the County of Salt Lake-started scheming.

“We got together and decided we needed Lloyd Pendleton,” Minkevitch said.

Pendleton was then an executive manager for the LDS Church Welfare Department, and he had a reputation for solving difficult managerial problems both in the United States and overseas. He’d also been involved in helping out with homeless projects in Salt Lake City, organizing volunteers, and donating food from the Bishop’s Storehouse. Dedicated to providing emergency and disaster assistance around the world as well as supplying basic material necessities to church members in need of assistance, the Church Welfare Department is like a large corporation in itself. It has 52 farms, 13 food-processing plants, and 135 storehouses. It also makes furniture like mattresses, tables, and dressers. If you’re a member of the church and you lose your job, your house, and all your money, you can go to your bishop and he’ll give you a place to live, some food, some money, and set you up with a job…no questions asked. All you have to do in return is some community service and try to follow the teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith. A system very much like Housing First-give them what they need, then work on their problems.

Minkevitch and Bate believed if they could get Pendleton to come on as the director of Utah’s Task Force on Homelessness he could mobilize the LDS, unite the different homeless-service providers, and sell the Housing First paradigm to the Legislature. Minkevitch’s agency had a close relationship with LDS leaders; the church had been a big donor for his shelter, The Road Home. Bate had worked with Lt. Gov. Olene Walker, who had just ascended to the governorship when Mike Leavitt was appointed to lead the Environmental Protection Agency. He asked her to write a letter to LDS elders, requesting that they “loan” Pendleton to the state. She did, and the church leaders said yes. It was a perfect marriage between church and state.

“The old model was well intentioned but misinformed. You actually need housing to achieve sobriety and stability, not the other way around.”

Once Pendleton took over the task force, he traveled to other cities to study their homeless programs. But he didn’t see anything he thought would work, at least in Utah. “I wasn’t willing to go to the Legislature until we could tell them we had a new goal and a new vision,” he said.

Then, in 2005, after a conference in Las Vegas, Pendleton shared an airport shuttle ride with Tsemberis and got a firsthand account of the Housing First trial. Tsemberis bore his testimony, as the Mormons would say, about the transformative power of giving someone a home.

“Going from homelessness into a home changes a person’s psychological identity from outcast to member of the community,” Tsemberis says. The old model “was well intentioned but misinformed. It is a long stairway that required sobriety and required stability in order to get into housing. So many people could never achieve that while on the street. You actually need housing to achieve sobriety and stability, not the other way around. But that was the system that was there. Some people called it a housing readiness industry, because all these programs were in business to improve people to get them ready for housing. Improve their character, improve their behavior, improve their moral standing. There is also this attitude about poor people, like somehow they brought this upon themselves by not behaving right.” By contrast, he adds, “Housing First provides a new sense of belonging that is reinforced in every interaction with new neighbors and other community members. We operate with the belief that housing is a basic right. Everyone on the streets deserves a home. He or she should not have to earn it, or prove they are ready or worthy.”

When I asked Pendleton if that struck a chord because Housing First seemed akin to the LDS Church Welfare Department, he was careful to insist that “the Mormon church is no different than other Christian churches in this way.” Whatever, he was sold.

Lloyd Pendleton is 74 years old, fit and spry with silver hair and pale-blue eyes that have the penetrating and somewhat mesmerizing stare of a border collie. He grew up relatively poor on a dairy farm and cattle ranch in a remote desert of western Utah and maybe has some cow dog in him.

“As a kid,” he says, “I was expected to do everything on the farm, from building fences to chopping wood to milking the cows. Every year I was given a new pair of work boots and a new pair of Levi’s. That was all my family could afford.”

He earned an MBA from Brigham Young University and was hired straight out of school by the Ford Motor Company in Dearborn, Michigan. “I remember my first day on the job, sitting at a table in the corporate headquarters, looking around and realizing everyone else had gone to Harvard or Yale, and I was just a country hick from Utah. It was intimidating, for sure, but I thought, ‘No one here can outwork me.'”

At Ford, Pendleton began to hone what he calls the “champion method” for getting results. Champions, according to Pendleton, have stamina, enthusiasm, a sense of humor, and they focus on solutions rather than process. Getting stuff done is more important than having meetings. A perfect meeting for Pendleton amounts to him clasping his hands and saying, “Let’s get going and not waste any more time.”

Pendleton asked Tsemberis to come speak to the state task force, which he did, twice. Then Pendleton called a meeting of “all the dogs in the fight” and announced that they were going to run a Housing First trial in Salt Lake City. He told them to come up with the names of 25 chronically homeless people, “the worst of the worst,” and they were going to give them apartments scattered around the city, no questions asked. If it worked for them, it would work for everybody.

“I didn’t want any ‘creaming,'” Pendleton said. “We needed to be able to trust the results.”

Many of the people in the room were uncomfortable with Pendleton’s idea. They were case managers and shelter directors and city housing officials who worked with “the worst of the worst” every day and knew they had serious personal problems-terrible alcoholism, dementia, paranoid schizophrenia. Something bad was sure to happen. There could be lawsuits. And who would be responsible? No, they thought, it will not work.

Pendleton, however, did not want to hear complaints. This was a small-scale trial, and he only wanted them to answer one question: “What do you need to get this done?”

So they did it. They ended up with 17 people and gave them apartments, health care, and services. They took people without a home and made them part of a neighborhood. And it worked, surprisingly well. After nearly two years, 14 were still in their apartments (the other three died), and they are still there today. They haven’t caused problems for themselves or their neighbors, Pendleton says.

Utah found that giving people supportive housing cost the system about half as much as leaving the homeless to live on the street.

The cost of housing and caring for the 17 people, over the first two years, was more than expected because many needed serious medical care and spent some time in hospitals. They were, however, the worst of the worst. Pendleton felt confident that, averaged out over the whole homeless population and over a period of years, they were looking at a break-even proposition or better-it would cost no more to house the homeless and treat them in their homes than it would to cover the cost of shelter stays, jail time, and emergency room visits if they were left on the street. And those “cashable” savings wouldn’t even include less quantifiable benefits for the rest of the state’s residents: reduced wait times at ERs, faster police response times, cleaner streets.

This is when Pendleton announced a 10-year plan to end chronic homelessness in Utah by 2015. But finding scattered-site housing wasn’t going to cut it. To house 2,000 chronically homeless people, they would build five new apartment complexes. Around 90 percent of the construction money would come from the Federal Low Income Housing Tax Credit program, which gives tax credits to large financial corporations that provide financing for housing authorities or nonprofits to build low-income housing-an average 6 percent profit on their investment. It’s a rather complicated and circuitous route, but it’s politically easier than getting lawmakers to allocate billions for poor people. The remaining 10 percent of construction costs would come from state taxes and charitable organizations. Most of the rent and maintenance on the units would come from federal Section 8 housing subsidies-and, at the time, Utah was fortunate enough not to have a long waiting list. On-site services, such as counseling, would largely be paid for by state and county general-fund dollars.

It took the task force only four years to build five new apartment buildings with units for 1,000 individuals and families. That, and an additional 500 scattered-site units, reduced the number of chronically homeless by almost three-quarters. And nine years into the 10-year plan to end chronic homelessness, Pendleton estimates that Utah’s Housing First program cost between $10,000 and $12,000 per person, about half of the $20,000 it cost to treat and care for homeless people on the street.

As anyone who’s followed social services can tell you, however, cheery annual reports can hide a world of dysfunction. So I go to see for myself.

Sunrise Metro was the first apartment complex built following the 2005 pilot study. It has 100 one-bedroom units for single residents, many of whom are veterans. Mark Eugene Hudgins is 58 years old and has brain damage. When I first start talking to him, I wonder if he’s been drinking.

“I always get hassled because I sound a little drunk,” he says. “My brain works a little slow. They drilled a hole in it.”

He had a motorcycle accident in Santa Ana, California, the year after graduating from high school. After that he spent 22 months in the Navy, then worked as a groundskeeper for the aerial field photography office of the Department of Agriculture for 13 or 14 years. He says he was homeless for five years before he came here, but he’s not sure: “My memory is a little fuzzy.”

“This is a nice place to live,” he says. “I put up with them and they put up with me, and it’s a good deal. I like it here.”

While we talk, two other residents come up to listen. One is in a wheelchair. His name is John Dahlsrud, 63, and he says he’s had MS for 45 years. The other guy looks like a weary Santa Claus-Paul Stephenson, 62, a Navy vet who lived for three years in the bushes behind a car dealership.

“The caseworkers are good,” Paul says. “They take us bowling on Saturdays. The apartment pays for one game, we pay for the second game.”

“They let you do what you want,” John adds, “as long as you keep things down to a minimum and don’t run up and down the halls naked.”

“Utilities are included, except for cable,” Paul says. “They gave everybody a free cellphone with 250 minutes a month. We get a pool table, a pingpong table, 60-inch television, eight recliner rockers. They give us food boxes once a month. I got 22 cans of tuna fish last month. There’s nothing to complain about.”

They each receive about $800 a month in Supplemental Security Income, and pay a third of that toward their rent. (The balance is paid via federal vouchers, along with some Utah funds.)

Over at Grace Mary Manor, I am given a tour by the county housing authority’s Kerry Bate-one of the men who helped persuade the LDS church to loan Pendleton to the task force. Grace Mary Manor is home to 84 formerly homeless individuals with disabling conditions such as brain damage, cancer, and dementia. You have to have a swipe card or get buzzed in at the front door, and there’s a front desk manager during the day and an off-duty sheriff at night. Bate explains that one of the biggest problems in giving homeless people a place to live is that they often want to bring their friends in off the street-they feel guilty. So there are rules to limit such visitations.

“It gives the people who live here a way out,” Bate says. “They can blame it on us.”

Tom Pinkerton, 67, from Red River, South Dakota, has cancer of the esophagus. He needs to have surgery, but first has to gain 10 to 20 pounds to make it through the anesthesia. (He has since passed away.) Howard Kelly, 44, from Denton, Texas, has brain damage from falling out of a car when he was a kid. David Simmons, 39, from Texas, was living under a bridge before coming here. I’m no doctor, but I’d guess he has some mental-health problems. Lorraine Levi says she’s “over 50.” Her boyfriend beat her up and broke her back. She needs surgery and is on strong doses of pain meds.

“The average person at Grace Mary was homeless for eight years before coming here, so their health condition is really poor,” Bate says.

On the third floor there’s a library with big leather chairs, nice wooden tables, and a portrait of Grace Mary Gallivan hanging above the fireplace. She died in 2000. Her father was a manager of a silver mine in Park City, and her husband was publisher of the Salt Lake Tribune. Her family foundation put up $600,000 for the construction of the apartment complex, matched by the foundation of the heirs to Utah’s first multimillionaire, David Eccles, who built one of the biggest banks in the West. From a window in the library you can look outside and see a gazebo for picnics and a volleyball court with evenly raked sand.

Bate introduces me to Steven Roach and Kay Luther, young caseworkers who check in on their clients every day to see what they need. They take them to the Fourth Street Clinic and Valley Mental Health, bring food from the food banks-pretty much anything they can do to help.

“The point is to have a service person on-site,” Bate says. “So if Sally Jo is having a crisis, we got somebody here who can help. Their goal isn’t to take everybody off the street and repair them and turn them into middle-class America. Their goal is to make sure they stay housed.”

“We have a guy who goes out to sleep in the park every month, and we have to go get him, talk him into coming back,” Roach says.

“There’s no mandate for participation in substance abuse or mental-health care, but we can certainly encourage it,” Luther says. “We had one guy who got completely clean from heroin and is off working in a furniture store.”

Bate shows me an empty apartment, a fairly spartan studio with linoleum floors, new sheets on the bed, the kitchen stocked with canned food, silverware, plates, etc.

“The church donated all of this,” Bate says. “Before we opened up, volunteers from the local Mormon ward came over and assembled all the furniture. It was overwhelming. For the first several years we were open, the LDS church made weekly food deliveries-everything from meat to butter and cheese. It wasn’t just dried beans-it was good stuff.” (The Utah Food Bank now makes weekly deliveries.)

I ask him if this is why the programs work so well in Utah-because of church donations.

“If the LDS church was not into it, the money would be missed, for sure,” he says, “but it’s church leadership that’s immensely important. If the word gets out that the church is behind something, it removes a lot of barriers.”

“Why do you think they do it?” I ask.

“Oh,” he says, “I think they believe all that stuff in the New Testament about helping the poor. That’s kind of crazy for a religion, I know, but I think they take it quite seriously.”

“Do you think you can meet the goal of eliminating chronic homelessness in Utah by 2015?” I ask.

“Yes,” Bate says, “we have a little less than 272 remaining unhoused, and that’s a number you can wrap your head around. Not like California and other places.”

“So do you think your success can be duplicated in other places?”

“I think it can be duplicated,” he replies. “San Francisco has Silicon Valley. Seattle has Bill Gates. Almost all of our larger cities have local philanthropic organizations that can help a lot with funding and building community support.”

And that’s the question, isn’t it? Can Housing First scale to areas where land and services are expensive, where NIMBYs are accordingly more powerful, places where the full organizational zeal and experience of the LDS church aren’t in evidence, and where data about the benefits of offering the homeless a permanent residence might not withstand the whims of politicians? In New York City, former Mayor Michael Bloomberg rolled out a well-regarded Housing First program focusing on mentally ill individuals. But he then gutted housing subsidies for the general homeless population, including families, after saying he thought they promoted passivity instead of “client responsibility.” Today, homelessness is the highest since the Great Depression, with 60,000 New Yorkers-including 26,000 children-on the streets, in the subway tunnels, and in the city’s sprawling network of 255 shelters, conveniently located far from the playgrounds of the 1 percent. “Every month I get a paper from Welfare saying how much they just paid for me and my two kids to stay in our one room in this shelter. $3,444! Every month!” one exasperated mom told The New Yorker. “Give me $900 and I’ll find me and my kids an apartment, I promise you.” The new mayor, Bill de Blasio, has pledged to reinvest in supportive and affordable housing, but 1 in 5 residents now live below the poverty line, and demand is high.

Former Mayor Michael Bloomberg slashed housing subsidies after saying he thought they promoted passivity instead of “client responsibility.” Today, 60,000 New Yorkers are homeless.

But the real test case might be California, where 20 percent of the nation’s homeless live. Los Angeles has 34,393 homeless people, more than a quarter of whom are chronically so. San Francisco has 6,408 homeless, Santa Clara County-home to San Jose and the greater Silicon Valley-has 7,567, and housing costs are among the highest in the nation. It takes three minimum-wage jobs to pay for an average one-bedroom apartment there. Tax credits for construction and Section 8 vouchers for rent don’t come close to the actual costs.

That’s the dilemma facing Jennifer Loving, the executive director of Destination: Home, a public-private partnership spearheading Santa Clara’s Housing First program. As in Utah, the leaders of Santa Clara’s initiative were able to marshal different agencies, nonprofits, and private groups, unifying their vision and goals to house the chronically homeless. “At first, it was tough to move out of the shelter way of doing things. It was new to all sit around the same table and change the way the system responds to homelessness,” Loving says.

Like Pendleton, they addressed the chronically homeless cases first. In 2011, in conjunction with a national effort called 100,000 Homes, they began a trial to house 1,000 people who’d been homeless for an average of 18 years and estimated to cost the system upward of $60,000 a year. “Our motto was, ‘Whatever it takes,'” Loving says. “We built the plane as we were flying it.” That meant lots of innovation along the way, such as creating a $100,000 flex fund to do things like pay off small dings on people’s credit, so they could qualify for vouchers and establish rental history: “So if Bob has an eight-year-old violation on his credit history, we’d just pay that off,” Loving says.

By the end of 2014, they had housed 840 people in apartments scattered around the county. The remaining 100 or so have rental subsidies but can’t find a place to live due to exceptionally high occupancy rates. Still, the trial was considered a big success-in part because supported housing only cost an estimated $25,000 per person-and Santa Clara County has now officially adopted the Housing First model. “We made a system out of nothing, and we used it like an assembly line to house people,” Loving says. “And the only thing in our way is the high cost of housing stock.”

So now they’re embarking on a five-year plan to house the county’s remaining 6,000 homeless. First, they’ve launched an extensive study on exactly how much homelessness actually costs taxpayers. Those costs are very hard to determine: There are so many agencies involved-hospitals, jails, police, detox centers, mental-health clinics, shelters, service providers-and they all keep separate records, separate sets of data used for separate purposes, all run on separate pieces of software. “Each department has an information system and a team that looks at the data,” says Ky Le, director of the Office of Supportive Housing for Santa Clara. “They have small teams who know their data best, how it’s configured and why, what’s accurate and what’s not.” Ky says that merging datasets has been “a tremendous effort,” but by integrating and analyzing it, Santa Clara hopes to better understand who’s already a “frequent flier” of clinics and jails, and, more tantalizingly, to develop an early warning system for who is likely to become one, and how they can be housed and cared for in the most cost-effective manner.

New housing needs to be found, or built, but with the market so tight, finding housing-any housing-is a huge challenge, one made worse when Gov. Jerry Brown slashed all $1.7 billion of the state’s redevelopment funds during the 2011 budget crisis. (Those funds have not rematerialized now that California has a huge budget surplus.) So they’re getting creative-“tiny homes, pod housing, stackable-we’re looking at it all,” Loving says. And they’re employing creative financing efforts, like “pay-for-success” bonds, in which investors (mostly foundations) would stake the construction funds and get a small return if the savings materialize for the county.

Advocates estimate it could take up to a billion dollars, half from grants and philanthropy, the other half in the form of county land and services. “The work we’re going to be doing in the next year,” Loving says, “is determining where and how to create new units and how much they are going to cost and where we can get the resources from-whether it’s private or public money. The money is all here. We have eBay, Adobe, Applied Materials, Google.” The hope is that the emphasis on quantified efficiency will persuade tech firms and billionaires obsessed with metrics that Housing First is a solid civic investment. “It’s fascinating because we have this problem we could totally solve if we wanted to,” Loving says. “We solve complicated problems all the time, right? Silicon Valley is an example of solving complicated problems all the time.”

If places as different-economically, demographically, politically-as Salt Lake City and Santa Clara County can make Housing First work, is there any place that can’t? To be sure, the return on investment will vary, depending on how you count the various benefits of fewer people living in the streets, clogging emergency rooms, and crowding jails. But the overall equation is clear: “Ironically, ending homelessness is actually cheaper than continuing to treat the problem. This would not only benefit the people who are homeless; it would be healing for the rest of us to live in a more compassionate and just nation,” Tsemberis says. “It’s not a matter of whether we know how to fix the problem. Homelessness is not a disease like cancer or Alzheimer’s where we don’t yet have a cure. We have the cure for homelessness-it’s housing. What we lack is political will.”

Gathering Interest

Gathering Interest Possibilities for Expansion

Possibilities for Expansion

Leo.

Leo.