When Dennis and Danielle McClung bought a foreclosed home in Mesa, Ariz., in 2009, their new yard featured a broken, empty swimming pool. Instead of spending a small fortune to repair and fill it, Dennis had a far more prescient idea: He built a plastic cap over it and started growing things inside.

Thus, with help from family and friends and a ton of internet research, Garden Pool was born. What was once a yawning cement hole was transformed into an incredibly prolific closed-loop ecosystem, growing everything from broccoli and sweet potatoes to sorghum and wheat, with chickens, tilapia, algae, and duckweed all interacting symbiotically to provide enough food to feed a family of five.

Within a year, Garden Pool had slashed up to three-quarters of the McClungs’ monthly grocery bill (they still buy things like cooking oil and coffee and, well, one can’t eat tilapia every day). Within five years, it’d spawned an active community of Garden Pool advocates – and Garden Pools – across the country and the world.

What began as a family experiment and blog is now a 501(c)3 nonprofit with a small staff. Garden Pool has been voted the Best Backyard Farm in Phoenix, gotten press from National Geographic TV and Wired and Make, and formed a Phoenix-area Meetup group that has nearly a thousand members. It’s attracted hundreds of local volunteers, students, and gardeners who’ve helped build a dozen more Garden Pool systems in and around Phoenix.

Scientists and engineers from Cornell University, Arizona State University, and even the space industry have all visited Garden Pool. This spring, “GP” volunteers paired up with Naturopaths Without Borders to travel to Haiti and build a Garden Pool there. Plus, Dennis says, “we’ve helped maybe three dozen being built across the country” through email and phone consultations, “from Florida to Toledo to Palm Springs.”

At first, McClung just wanted his own family to live more sustainably. Now that he’s seen the all the traction these ideas are getting, and how awesomely productive a Garden Pool can be, he says, “I want everyone else to build great systems.”

And these systems are pretty great. Instead of soil, the Garden Pool’s plants grow on clay pellets or coconut coir. Excess moisture drips into the pond below, and that, plus a rain catchment system, means that the whole thing requires a tiny fraction of the water used in a conventional garden. This is especially crucial in a place like Mesa, which gets just a little over nine inches of rain per year.

Instead of commercial fertilizer, chicken droppings fall through wire mesh strung across the pool’s deep end, nourishing the algae and duckweed in the pond below. The tilapia eat the pond plants, release their own nitrogen-rich excrement, and the fish water then gets funneled (using a solar-powered electric pump) into the hydroponics system that grows the family produce.

The McClungs have added pygmy goats and a bunch of fruit and nut trees to the backyard mix, so their mini farm is starting to look a lot like a very hopeful – and very delicious – urban future.

Dennis says building your own Garden Pool is not as labor-intensive and complex as it sounds. In addition to free online tutorials like “Getting Started in Barrelponics” and “Growing Duckweed,” McClung teaches GP certification courses; so far, he’s certified about 20 “GP” enthusiasts in Arizona and about 12 more during the trip to Haiti this spring. He plans to help a few recent grads start their own Meetup groups in Los Angeles and New York.

He also just released the second edition of Garden Pool’s extensive how-to book, featuring 117 pages of detailed instructions, illustrations, photos, and QR codes that link to video tutorials. His goal is to encourage aspiring Garden Poolers to build and maintain their own aquaponics greenhouses, whether or not they’ve done anything remotely like it before, and whether or not they even have a pool. (One of Garden Pool’s main taglines is “use an old pool or just dig a pond!”)

Thanks to endless experimentation with new crops and filters and catchment systems, McClung claims his backyard is now “basically a Frankenstein laboratory” and not quite as pretty as the sparkling Garden Pool replicas and spinoffs he’s helped build around town. Various experiments have met with varying degrees of success (blueberries and amaranth didn’t do as well as eggplant and asparagus, for instance), but the list of things that grow like weeds in Garden Pool is long (McClung advises you to check out page 96 of his book).

He manages pest control by doing things like adding ladybugs for the aphids and selecting plants like marigolds and garlic, which repel whiteflies and spider mites, respectively. Since the system is closed and controlled, it’s a pretty fantastic way to experiment with organic gardening methods.

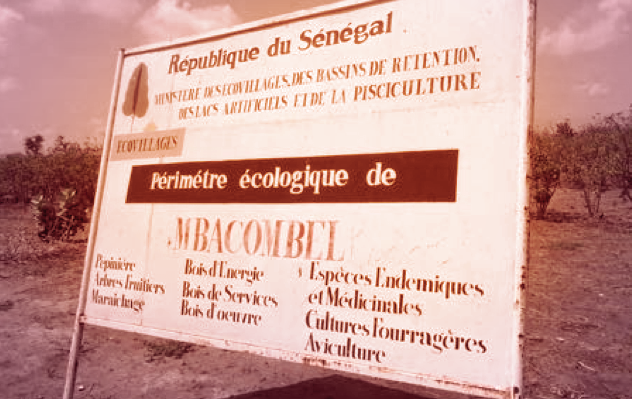

As far as they’ve come in the past five years, though, Dennis says they’re just rolling up their sleeves. Now that all the nonprofit paperwork is settled, Garden Pool staff can apply for grants, and, he hopes, “hop from place to place and make stuff happen.” He’d like to help build more Garden Pools in Haiti, Africa, South America, and across the globe, and eventually become something of an international hub for closed-loop system research.

Although Garden Pool is Dennis’s full-time occupation and has been for some years now, “it’s not a job yet,” he insists. “I love it. I dream about it. What inspires me is watching families’ lives being changed, watching communities change, observing the change.”