Meditation for Beginners: 20 Practical Tips for Quieting the Mind : zen habits

Editor’s note: This is a guest post from Todd Goldfarb at the We The Change blog.

Meditation is the art of focusing 100% of your attention in one area. The practice comes with a myriad of well-publicized health benefits including increased concentration, decreased anxiety, and a general feeling of happiness.

Although a great number of people try meditation at some point in their lives, a small percentage actually stick with it for the long-term. This is unfortunate, and a possible reason is that many beginners do not begin with a mindset needed to make the practice sustainable.

The purpose of this article is to provide 20 practical recommendations to help beginners get past the initial hurdles and integrate meditation over the long term:

1) Make it a formal practice. You will only get to the next level in meditation by setting aside specific time (preferably two times a day) to be still.

2) Start with the breath. Breathing deep slows the heart rate, relaxes the muscles, focuses the mind and is an ideal way to begin practice.

3) Stretch first. Stretching loosens the muscles and tendons allowing you to sit (or lie) more comfortably. Additionally, stretching starts the process of “going inward” and brings added attention to the body.

4) Meditate with Purpose. Beginners must understand that meditation is an ACTIVE process. The art of focusing your attention to a single point is hard work, and you have to be purposefully engaged!

5) Notice frustration creep up on you. This is very common for beginners as we think “hey, what am I doing here” or “why can’t I just quiet my damn mind already”. When this happens, really focus in on your breath and let the frustrated feelings go.

6) Experiment. Although many of us think of effective meditation as a Yogi sitting cross-legged beneath a Bonzi tree, beginners should be more experimental and try different types of meditation. Try sitting, lying, eyes open, eyes closed, etc.

7) Feel your body parts. A great practice for beginning meditators is to take notice of the body when a meditative state starts to take hold. Once the mind quiets, put all your attention to the feet and then slowly move your way up the body (include your internal organs). This is very healthy and an indicator that you are on the right path.

8) Pick a specific room in your home to meditate. Make sure it is not the same room where you do work, exercise, or sleep. Place candles and other spiritual paraphernalia in the room to help you feel at ease.

9) Read a book (or two) on meditation. Preferably an instructional guide AND one that describes the benefits of deep meditative states. This will get you motivated. John Kabat-Zinn’s Wherever You Go, There You Are is terrific for beginners.

10) Commit for the long haul. Meditation is a life-long practice, and you will benefit most by NOT examining the results of your daily practice. Just do the best you can every day, and then let it go!

11) Listen to instructional tapes and CDs.

12) Generate moments of awareness during the day. Finding your breath and “being present” while not in formal practice is a wonderful way to evolve your meditation habits.

13) Make sure you will not be disturbed. One of the biggest mistakes beginners make is not insuring peaceful practice conditions. If you have it in the back of your mind that the phone might ring, your kids might wake, or your coffee pot might whistle than you will not be able to attain a state of deep relaxation.

14) Notice small adjustments. For beginning meditators, the slightest physical movements can transform a meditative practice from one of frustration to one of renewal. These adjustments may be barely noticeable to an observer, but they can mean everything for your practice.

15) Use a candle. Meditating with eyes closed can be challenging for a beginner. Lighting a candle and using it as your point of focus allows you to strengthen your attention with a visual cue. This can be very powerful.

16) Do NOT Stress. This may be the most important tip for beginners, and the hardest to implement. No matter what happens during your meditation practice, do not stress about it. This includes being nervous before meditating and angry afterwards. Meditation is what it is, and just do the best you can at the time.

17) Do it together. Meditating with a partner or loved one can have many wonderful benefits, and can improve your practice. However, it is necessary to make sure that you set agreed-upon ground rules before you begin!

18) Meditate early in the morning. Without a doubt, early morning is an ideal

time to practice: it is quieter, your mind is not filled with the usual clutter, and there is less chance you will be disturbed. Make it a habit to get up half an hour earlier to meditate.

19) Be Grateful at the end. Once your practice is through, spend 2-3 minutes feeling appreciative of the opportunity to practice and your mind’s ability to focus.

20) Notice when your interest in meditation begins to wane. Meditation is

hard work, and you will inevitably come to a point where it seemingly does not fit into the picture anymore. THIS is when you need your practice the most and I recommend you go back to the book(s) or the CD’s you listened to and become re-invigorated with the practice. Chances are that losing the ability to focus on meditation is parallel with your inability to focus in other areas of your life!

Meditation is an absolutely wonderful practice, but can be very difficult in the beginning. Use the tips described in this article to get your practice to the next level!

Read more about personal development from Todd Goldfarb on his blog, We The Change.

How India Wants To Use Coal To Expand Solar Power

CREDIT: AP Photo/Rajanish Kakade

How could the world’s third-largest coal consumer use coal to get more solar power?

India’s government is ordering its state-owned utility, NTPC, to sell electricity from solar power along with electricity from coal-fired power in order to boost solar’s position in the country. The decision, dating back to the middle of July but first reported by Bloomberg, mandates that the utility sell currently-cheaper coal power bundled into one unit with solar power, which is currently more expensive.

This could have the effect of expanding the production and usage of solar power, making it less expensive for distribution companies to bring it to customers. India’s power distribution companies are also run by the government, and had been losing money when buying more expensive electricity and selling it at a lower price.

The other effect, of course, will be the continued use of quarter-century-old coal plants that will get their power output bundled with newer solar plants coming online. This helps guarantee the coal plants’ operation, as well as their carbon emissions.

“These plants are already 25 years old,” Rupesh Agarwal, a partner at BDO India LLP, told Bloomberg. “Will they function for that many more years? Do we need to extend the lives of these plants to bundle with solar energy when solar on a stand-alone basis is becoming competitive?”

NTPC will construct 15 gigawatts of solar over the next four years as a part of this deal.

Coal India, the largest coal company in the world, has seen the value of solar for years – the company has installed solar panels at mine installations across the country.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi committed to 100 gigawatts of solar capacity in the next seven years, which will be a large increase from the current 4.5 gigawatts. This capacity will be an almost even split between distributed rooftop installations (about 40 gigawatts) and larger grid-connected solar farms.

Boosting solar capacity to 100 gigawatts would be hard, as the Indian consulting firm Bridge to India recently estimated the country was on track to install 31 gigawatts over the next four years.

CREDIT: Courtesy of Bridge To India

Should they achieve it, this will help achieve the other major energy goal put forth by the government: bringing electricity to the 400 million households that currently do not have it. This means more power, from everywhere. Renewable prices – especially solar – are dropping, which helps those trying to limit the growth of India’s carbon emissions. At the same time, India has become more and more dependent upon imported fossil fuels – including coal despite significant domestic reserves. Recent reports have predicted that India will outpace China in coal imports in the near future.

“Despite its significant coal reserves, India has experienced increasing supply shortages as a result of a lack of competition among producers, insufficient investment, and systemic problems with its mining industry,” according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. “Although production has increased by about 4% per year since 2007, producers have failed to reach the government’s production targets.”

China has committed to slowing and reversing its coal usage due to climate and air quality concerns. A recent study found that over 17 percent of all deaths in China are related to high pollution levels. Yet Indian cities have to struggle with some of the worst air pollution in the world.

It’s not just solar that has a lot of potential in India. A study released last week found that India’s wind energy capacity is much higher than originally anticipated – 302 gigawatts for turbines with hubs reaching 100 meters, compared with the 100 gigawatts previously thought.

The government is also trying to keep energy demand low – last month, Energy Minister Piyush Goyal committed India to replace all conventional streetlights with LEDs within two years. This will cut demand almost to almost a third of current levels – 3,400 megawatts to 1,400 megawatts. Fortunately for them, LED streetlight prices have dropped almost by half in the last year.

Results Driven Land-Use Planning – Spacing National

In North America, cities are increasingly burdened with a growing list of required infrastructure maintenance and replacements. With few options for generating tax revenue, these obligations are stretching municipal budgets thin, leading to uncertain and lengthy conversations with higher levels of government about funding. This process delays the critical infrastructure upgrades that we need today rather than tomorrow.

Rather than seeking ways to maximize the return on existing infrastructure, North America is obsessed with building newer and bigger infrastructure, which does not match current demand. According to Strong Towns, this new-infrastructure fetish is literally bankrupting our cities. For example, in Vancouver, Canada the B.C. Liberal provincial government has replaced the Port Mann bridge with one of the world’s largest bridges, based on impractical automobile growth predictions. The bridge has consistently fallen short of the predicted traffic projections and its debt continues to grow with little or no returns on billions of public dollars. The B.C. Liberal provincial government is in the midst of repeating the same mistake again by replacing the George Massey tunnel with an overbuilt and overcapacity billion dollar bridge that will never be able to pay for itself.

This approach to development can be seen in many cities across North America and fails to deliver the results we need today. In many cases, cities opt for expensive and grand projects that take years to reach fruition. So what’s the alternative? At Slow Streets, we believe that Amsterdam provides a great development model that delivers short-term results efficiently and effectively. This article provides a quick case study of the Amsterdam approach to development.

Lay the Bones for Complete Neighbourhoods to Achieve Results-Driven City Building

Clearly the best solution is to prevent overbuilding infrastructure from the start. This is where Amsterdam comes in. Amsterdam often plans its new neighborhoods and infrastructure requirements to match existing demand. In North America, cities often build the residential uses first and then eventually build community amenities and commercial uses. This is an absurd way to build our urban landscapes, as incomplete neighbourhoods force residents to commute elsewhere in the city. This also places an unnecessary, unpredictable strain on already overburdened public services like roads and schools. Parents often move into these new neighborhoods with the promise of playgrounds, schools, or community centres that never come.

Amsterdam has understood this, so when the demand for more housing or public services requires them to revitalize an existing neighborhood or build a new one, they will often ensure there is transit route servicing the area first. While it may seem to make little sense to provide transit to nowhere, it ensures that the bones are in place to support a healthy and complete neighborhood right from the start. Thinking about transit right away will help ensure successful transit geometries. Reliable transit services will minimize the need for automobiles and the associated congestion, pollution, and dangers to our children and family members they bring.

Next, the city will usually then proceed to invest in a public facility such as a library, community centre, museum or school. This will serve two purposes: first it will ensure that the new public service amenity will closely match pent up demand, relieving pressure from other overcapacity public services. Secondly, it will create predictable demands in the area and spur spill-over demands such as a coffee shop, a neighborhood drinking hole or other commercial uses. Based on the demand that grows around the public amenity, the government can then more accurately gauge the need for other public services in the area and incrementally build out the appropriate mix of residential and commercial uses.

Taking the demand based public service amenity city building approach ensures that we closely match the infrastructure demands with residential requirements like schools, transportation and public services. As a result, one maximizes the return on investment from public dollars. Furthermore, one avoids overbuilding too much infrastructure that is not operating at an efficient capacity and minimize the need for more taxes. While this approach will take significant leadership and cohesive civic staff culture, Amsterdam provides several other examples for short-term urban land use corrections to meet unfulfilled demands now.

Adaptive Reuse

In terms of balancing the infrastructure deficit, the best solution is often the one that is already built. In Canada, our heritage buildings are treated with little value. For example, in Edmonton several of the historic buildings and infrastructure built in the growth boom of the early 1900’s – such as the Rossdale Power Plant, the Walterdale Bridge or the McDougall United Church – are requiring repairs. Incredulously, the conversations often results in demolition.

While these 100 year old buildings may no longer be able to serve their original purpose, they were built in a time when things were built to last (as proven by their existence still today). Modern buildings today are often only built to last twenty years. Therefore, it is in our best interest to set aside a little bit of maintenance funding and to be flexible with tolerated uses within these precious historic buildings. These buildings not only create economic value for the surrounding area, but create cultural value by connecting us to our shared past. Additionally, as community landmarks, they play a critical role in wayfinding and creating a sense of place.

Amsterdam has examples of this creative reuse of infrastructure in spades: whether it is a radio tower rig converted into a restaurant, a former industrial crane converted into a hot-tub, an old water tower converted into a flexible development show room, a tram storage facility converted into a shopping and food court facility, warehouses converted into bars or event centres, oil tanks or historic storage buildings are converted into community centres….the list goes on. Amsterdam understands the savings and value generation for the public that come from maintaining and repurposing historic infrastructure.

Part of the reason for this prolific reuse of infrastructure is mixed-use zoning which establishes the tools needed right from the start, in order to ensure that a neighbourhood is complete. The Amsterdam planning department does not blindly follow rigid guidelines dictating what uses can go where. Rather they use sound, case-by-case judgment to determine whether specific land uses are appropriate in relation to their context. However, as a rule, one notices that the repurposing of structures ensures that the new buildings meet a high level of architectural standard. This is critical for ensuring that the building creates value in its context.

If the cost is prohibitive to reuse a building in a specific way, first try to change the regulations. If that fails, find a more cost effective way to use the building. Even if the municipality donates the space for free (more on this later), this can serve to generate more value from new business taxes or the public life new inhabitants create. In the end, the reuse of historic buildings serves to create an interesting, adaptable and resilient city. I mean, a hot-tub at the top of a crane, how cool is that?

Lighter, Quicker, Cost Effective

Finally, we need the flexibility to build critical infrastructure now, not two to three years from now. Often, our current regulations structure delay the building of the critical infrastructure that we need today. At Slow Streets, we believe that we should change them or treat them more as guidelines. Common sense should prevail before requiring lengthy and capital intensive studies or reviews. Often any solution is better than waiting years for the funding of the perfect solution. Not only can light, quick and temporary solutions be built to the high standards of permanent solutions, but they can also be adapted easier.

To demonstrate: What if more office space or student housing is required now and capital is scarce? In Amsterdam they would build temporary, but attractive housing using recycled shipping containers, until funding can be acquired to replace them with brick and mortar residences.

Another example is the NDSM – an artist work centre inhabiting a repurposed, abandoned ship building warehouse. To quickly build working quarters, the City opted to reuse shipping containers. The result is a vibrant, multipurpose and dynamic space for people to experiment with art and other entrepreneurial endeavors.

In another case, there was an empty industrial land that the city of Amsterdam wanted to convert into an office park called De Ceuvel. The only problem is that the land is contaminated with industrial chemicals. Most municipalities are faced with the choice of expensive excavation and soil replacement or letting the chemicals naturally breakdown (which takes several years). If you live in North America, you can probably recall at least one property – such as a decommissioned gas station – which has sat empty with a cheap chain-link fence around it, serving as an eyesore and contributing little in the way of fostering new businesses or generating tax revenues. In Canada, such properties exist ironically on some of the most productive properties on popular retail streets such as Whyte Avenue in Edmonton or Denman Street in Vancouver.

Amsterdam decided to go with the latter letting the chemicals breakdown, however they did not want the land to sit empty. As a solution, Amsterdam leased the land commercially at no cost to young entrepreneurs for a period of 10 years. There was still the sticking point of the contaminated ground, but as always, the Dutch are very practical with their solutions.

Dutch regulations require that decommissioned boats must be disposed of properly. This can come at a high cost. The City decided that several of these boats would be diverted from the waste system and be repurposed as offices. Finally, an elevated boardwalk was installed to keep people off the contaminated ground. Nearby a restaurant and bar has been built and, in the end, an interesting office park with a stunning view of Amsterdam and the IJ river is available for budding enterprises (at no cost) while adding to the tax revenues. All of this while cleaning up contaminated land and reusing materials.

Conclusion

In these days of limited municipal budgets and growing infrastructure requirements, it is a blatant abdication of our responsibilities for our cities to not invest in results now. We do not need the perfect solution, we need something that will maximize benefits for today until a suitable replacement can be made. Ensuring that we start new neighbourhoods with the necessary tools and public amenities to create a healthy and complete community, will ensure that cities can recapture the value created from public investments. Utilizing our existing stock of infrastructure more efficiently will save all of us money down the line, and at the same time, generate more economic and community value. Finally, changing our government structure and culture will payoff in spades down the road by better matching the infrastructure demands with the citizen requirements.

***

Slow Streets is a Vancouver based Urban Design and Planning

group providing original evidence for people oriented streets.

Music as Medicine? The Sexy Idea with a Non-Sexy Timeline.

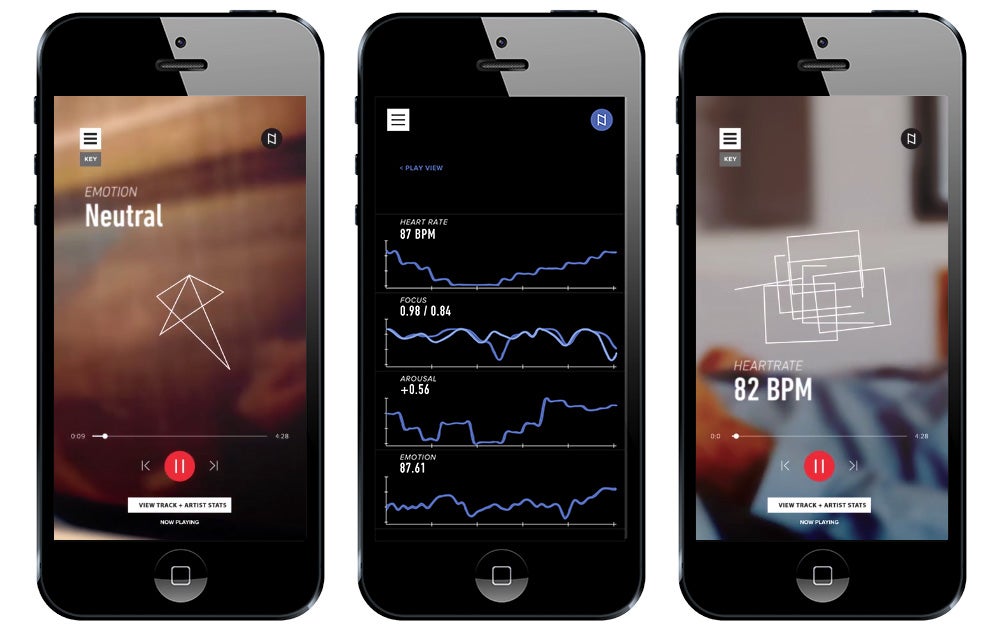

Festival-goers at this year’s SXSW saw their share of product demos, including one for The Sync Project. The venture, backed by Boston-based startup creator PureTech,overlays biometric data and predictive technology to better understand music’s impact on the body and the brain. Through wearables, the technology acts as a sort of FitBit / Spotify hybrid, tracking everything from arousal to heartbeat to focus.

By decoding how songs influence our brains and bodies, The Sync Project’s goal is to harness music to improve health. Music can be a science, as formulaic pop hits demonstrate. And with songs already pumping us up at the gym or soothing us after a bad day, it’s not a stretch to envision a world where artists like Taylor Swift or One Direction craft tunes to treat Alzheimer’s, anxiety or even autism. “We want to scientifically design therapies for different conditions,” says Alex Kopikis, one of the company’s co-founders.

But while the next Snapchat can arrive overnight, biotech companies must cycle through rounds of clinical trials and navigate rigorous regulatory landmines. So, despite its March unveiling, The Sync Project’s solutions are still likely years away. Unpredictable timeframes highlight the challenges facing biotech companies competing for buzz alongside traditional tech startups, and the creative ways they are maintaining momentum.

Listening as medicine

The Sync Project believes song data could shape users’ physiology and mood, by anticipating how listeners’ bodies and brains respond to musical elements. “Every note has information in it,” says Tristan Jehan, an advisor to The Sync Project. His audio fingerprinting service was acquired by Spotify last year and builds recommendation algorithms to decipher the similarities between genres, artists and songs.

Image Credit: The Sync Project

But for companies looking to harness that data, a lot remains unproven. “The problem with music and medicine is that everyone wishes that music is beneficial and that it is an easy fix,” says Nadine Gaab, an assistant professor of pediatrics at the Boston Children’s Hospital /Harvard Medical School. “If you really go hardcore down to the evidence, there isn’t much.”

Related: Researchers Are Using Yelp to Predict When a Restaurant Will Shut Down

While a large body of research ties music to physiological benefits like boosting cognition in dementia patients or improving verbal abilities in autistic children, some experts believe most of these studies would not withstand rigorous evaluation. Many studies linking music and health “are not completely well-designed,” says Ketki Karanam, a Harvard-educated biologist and a co-founder at The Sync Project.

Not all music therapists are trained for experimental work and studies often suffer from small sample sizes, mismanaged control groups and a reliance on subjective feedback. “It’s pretty sad how few of these studies are well executed, controlled randomized trials,” says Gaab.

“People have a tendency to oversimplify things,” adds Robert Zatorre, a neurologist at McGill University and a scientific advisor to the company. It’s natural for us to be drawn to “a sexy story,” he explains, even if the reality is less immediate.

Competing for dollars and buzz

Biotech offers its own challenges to innovators. While software solutions can launch in days or months, proper scientific testing can push biotech launches far into the distance. Alkili, another PureTech venture, was announced in 2012 but might not come to market until 2016 or later. Says Eddie Martucci, Akili’s co-founder, its progress rate still beats most scientific advances. “Usually when you hear about an innovation in the medical world, you hope that your kids can tap into that. So if the timeline is a couple years? That’s amazing.”

Unpredictable timing can dampen funding, however. Venture capital backing for biotech and pharma dropped 50 percent between 2010 and 2015, according to PitchBook, a Seattle-based data provider on private markets. This drop came, PitchBook says, because biotech projects can “take longer to successfully build, hurting returns.”

Related: Google to Break Ground on Life-Prolonging Research Facility

Investors familiar with health and biotech see long timelines as a protective barrier against competition, says Sam Sia, a faculty member in biomedical engineering at Columbia University and the founder of Harlem Biospace, a biotech incubator in New York City. Still, traditional tech investors new to the space “may be discouraged that the process takes longer than they’d hoped.”

Biotech also competes for attention with companies that don’t need scientific backing. Recently more than 70 prominent psychologists, cognitive scientists and neuroscientists wrote an open letter to companies making certain brain training software that the researchers felt exploited seniors’ anxieties about cognitive declines and made “exaggerated and misleading claims.”

“There are a lot of companies marketing products, making claims that we wouldn’t be comfortable with,” says Daphne Zohar, PureTech’s founder, CEO and managing partner. “Before putting a product on the market, Pure Tech’s strategy is to first put it through rigorous testing, the same process if this was a medical device or a drug.”

This summer PureTech raised $171 million in its initial public offering on the London stock exchange. That money, along with the $100 million the company raised in funding earlier this year, will be reinvested into its portfolio of individual companies, allowing them to launch at their own pace, says Zohar.

While many of Pure Tech’s investors focus on healthcare, and are familiar with the often long road to clinical validation, a large percentage are traditional tech investors. Which makes sense, as Pure Tech straddles both sectors. “This is a new industry, so it’s not going to be exactly like tech and it’s not going to be exactly like traditional biotech,” says Zohar. “The timelines to market will be shorter than traditional biotech, but the things we are doing take longer than just putting a product out on the market.”

Walking the line

Leading a buzzy, disruptive biotech company without running afoul of the FDA means walking a tricky tightrope. When personal genomics service 23andMe launched in 2008, it blazed trails and helped merge the tech and biotech world, says Sia.

Related: Meet Color Genomics, the Startup That Wants to Make Genetic Testing Less Expensive

But the FDA shut down much of its testing operation in 2013. And so the company was forced to split its strategy to focus mostly on ancestry reports, a consumer product that made no medical claims, while it worked with regulators. The approach, while slow-going, got results. It received approval for a Bloom syndrome test this past February.

Companies like The Sync Project will need to strike a similar balance. Until its full launch, the company is strengthening its role as a thought leader in music and tech, leveraging the expertise of its advisors from MIT and Spotify. In July, the company hosted a workshop in Montreal at McGill University, inviting researchers in music, neuroscience, psychology and medicine to discuss the state of technology in current research on music’s impact on the mind and body. A new partnership with Berklee College of Music in Boston will include collaborative research efforts, joint-course development, and an internship program for music therapy students between the school and The Sync Project.

In the meantime, the company is building a special research platform to facilitate rigorous, well-designed clinical trials, run by independent researchers, to determine whether or not music has a palliative effect on a host of conditions and diseases. Most of the data the company collects will be accessible to researchers, says Ahtisaari, although the company is still developing a system in which this information can be shared.

These trials, which use The Sync Project’s app, are slated to begin this month. In addition, the company wants to conduct large-scale, open studies, in which anyone who wants to participate can download the app, track how songs impact their biometric data and answer a few survey questions, says Marko Ahtisaari , The Sync Project’s recently appointed CEO and former head of design at Nokia. This hybrid approach — collecting large amounts data in conjunction with smaller data sets from clinical trials — will not only facilitate a more diverse and rigorous test sample, but also likely accelerate the app’s time to market, says Ahtisaari.

“Our key motivation is to enable researchers to design and carry out better studies that will identify music’s potential,” says Karanam.

While such measures aren’t perfect, they’re a start. “These things do take quite a bit of time,” says Zatorre. “You have to do things carefully.”

Related: Are You an Empathetic or Analytical Thinker? Your Music Playlist May Hold the Answer.

Ways to Help Syrian Refugees

Originally Written by Tumblr User rrrrnessa.

That Syrian child whose picture is being shared had a name, his name was Aylan Kurdi and he was 3 years old. He had a brother name Galip who was 5 years old who died as well, along with their mother. He had a family and would have had a bright future had the International community done anything to stop the attrocities, had the International community done anything to make seeking reguge easier and more humane. When you share his picture as some nameless person in order to spark outrage, in order to pat yourself on the back for doing *something* or for likes and shares you engage in the dehumanization of a 3 year old child. He had a name, Aylan.

And instead of sharing such a triggering, dehumanizing, and disgusting image to make yourself feel good you could donate money to the many organizations that are attempting to help refugees find shelter, that are attempting to feed them, you could start petitions, you could share the history of the war (words not just pictures), you could write letters to legislators that represent you to help put the pressure on them to act regarding the refugee crisis. When enough people actually DO something…things get done. But when you share a disturbing picture which further fuels our desensitization to violence you’re not doing anything other than appeasing your own ego.

So here are some ways to *actually* help:

1. Doctors Without Borders is providing medical aid in and around Syria. If you call this number you can ensure your funds go directly to Syrian refugees 1-888-392-0392.

2. World Visions works in Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan to provide clean and sanitizing water. You can donate by calling 1-800-562-4453.

3. CARE operates multiple refugee centers in Syria, Jordan and Lebanon and you can donate to them by calling 1-800-521-CARE

4. World Food Program will provide food to Syrians and other refugees…you can donate at wfp.org

5. Islamic Relief USA is also providing food, water, and shelter and you can donate to them by visitinghttp://www.irusa.org/emergencies/syrian-humanitarian-relief/

6. You can also donate to SavetheChildren.org which provides things such as diapers, clothing, and food.

7. You can donate to the U.N refugee agency here: http://donate.unhcr.org/gbr/general/

8. You can purchase items on an Amazon wishlist specifically for the refugees stranded in Calais.https://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/aw/ls?lid=1P2RJO27Q6N2T&tag=independen058-21&ty=wishlist

9. You can sign the following petition to have more asylum seekers accepted in the U.Khttps://petition.parliament.uk/petitions/105991

10. You can donate here to help the refugees stuck in the Balkans get shelterhttps://www.indiegogo.com/projects/help-us-give-them-shelter-on-their-way-to-refuge–2#/

But you can also do more, get involved in grassroots organizations locally, fundraise with your church/mosque/temple. Write and start new petitions. Protest in front of embassies or other places of governance.

Really, there are many ways to help and sharing a picture of a young child…a BABY without his name, his story, anything is not one of them.

Limits to Growth was right. New research shows we’re nearing collapse | Cathy Alexander and Graham Turner

The 1972 book Limits to Growth, which predicted our civilisation would probably collapse some time this century, has been criticised as doomsday fantasy since it was published. Back in 2002, self-styled environmental expert Bjorn Lomborg consigned it to the “dustbin of history”.

It doesn’t belong there. Research from the University of Melbourne has found the book’s forecasts are accurate, 40 years on. If we continue to track in line with the book’s scenario, expect the early stages of global collapse to start appearing soon.

Limits to Growth was commissioned by a think tank called the Club of Rome. Researchers working out of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, including husband-and-wife team Donella and Dennis Meadows, built a computer model to track the world’s economy and environment. Called World3, this computer model was cutting edge.

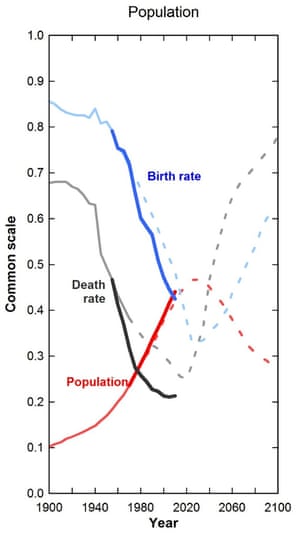

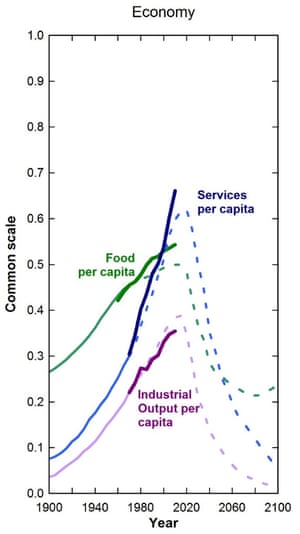

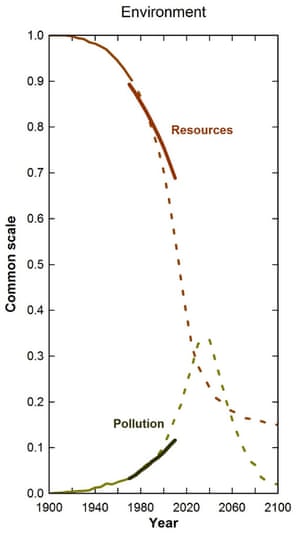

The task was very ambitious. The team tracked industrialisation, population, food, use of resources, and pollution. They modelled data up to 1970, then developed a range of scenarios out to 2100, depending on whether humanity took serious action on environmental and resource issues. If that didn’t happen, the model predicted “overshoot and collapse” – in the economy, environment and population – before 2070. This was called the “business-as-usual” scenario.

The book’s central point, much criticised since, is that “the earth is finite” and the quest for unlimited growth in population, material goods etc would eventually lead to a crash.

So were they right? We decided to check in with those scenarios after 40 years. Dr Graham Turner gathered data from the UN (its department of economic and social affairs, Unesco, the food and agriculture organisation, and the UN statistics yearbook). He also checked in with the US national oceanic and atmospheric administration, the BP statistical review, and elsewhere. That data was plotted alongside the Limits to Growth scenarios.

The results show that the world is tracking pretty closely to the Limits to Growth “business-as-usual” scenario. The data doesn’t match up with other scenarios.

These graphs show real-world data (first from the MIT work, then from our research), plotted in a solid line. The dotted line shows the Limits to Growth “business-as-usual” scenario out to 2100. Up to 2010, the data is strikingly similar to the book’s forecasts.

As the MIT researchers explained in 1972, under the scenario, growing population and demands for material wealth would lead to more industrial output and pollution. The graphs show this is indeed happening. Resources are being used up at a rapid rate, pollution is rising, industrial output and food per capita is rising. The population is rising quickly.

So far, Limits to Growth checks out with reality. So what happens next?

According to the book, to feed the continued growth in industrial output there must be ever-increasing use of resources. But resources become more expensive to obtain as they are used up. As more and more capital goes towards resource extraction, industrial output per capita starts to fall – in the book, from about 2015.

As pollution mounts and industrial input into agriculture falls, food production per capita falls. Health and education services are cut back, and that combines to bring about a rise in the death rate from about 2020. Global population begins to fall from about 2030, by about half a billion people per decade. Living conditions fall to levels similar to the early 1900s.

It’s essentially resource constraints that bring about global collapse in the book. However, Limits to Growth does factor in the fallout from increasing pollution, including climate change. The book warned carbon dioxide emissions would have a “climatological effect” via “warming the atmosphere”.

As the graphs show, the University of Melbourne research has not found proof of collapse as of 2010 (although growth has already stalled in some areas). But in Limits to Growth those effects only start to bite around 2015-2030.

The first stages of decline may already have started. The Global Financial Crisis of 2007-08 and ongoing economic malaise may be a harbinger of the fallout from resource constraints. The pursuit of material wealth contributed to unsustainable levels of debt, with suddenly higher prices for food and oil contributing to defaults – and the GFC.

The issue of peak oil is critical. Many independent researchers conclude that “easy” conventional oil production has already peaked. Even the conservative International Energy Agency has warned about peak oil.

Peak oil could be the catalyst for global collapse. Some see new fossil fuel sources like shale oil, tar sands and coal seam gas as saviours, but the issue is how fast these resources can be extracted, for how long, and at what cost. If they soak up too much capital to extract the fallout would be widespread.

Our research does not indicate that collapse of the world economy, environment and population is a certainty. Nor do we claim the future will unfold exactly as the MIT researchers predicted back in 1972. Wars could break out; so could genuine global environmental leadership. Either could dramatically affect the trajectory.

But our findings should sound an alarm bell. It seems unlikely that the quest for ever-increasing growth can continue unchecked to 2100 without causing serious negative effects – and those effects might come sooner than we think.

It may be too late to convince the world’s politicians and wealthy elites to chart a different course. So to the rest of us, maybe it’s time to think about how we protect ourselves as we head into an uncertain future.

As Limits to Growth concluded in 1972:

If the present growth trends in world population, industrialisation, pollution, food production, and resource depletion continue unchanged, the limits to growth on this planet will be reached sometime within the next one hundred years. The most probable result will be a rather sudden and uncontrollable decline in both population and industrial capacity.

So far, there’s little to indicate they got that wrong.

The shockingly simple, surprisingly cost-effective way to end homelessness

Why aren’t more cities using it?

By Scott Carrier | Tuesday Feb. 17, 2015 06:00 AM | Photos by Jim McAuley

By Scott Carrier | Tuesday Feb. 17, 2015 06:00 AM | Photos by Jim McAuley

It’s early December, 10:30 in the morning, and Rene Zepeda is driving a Volunteers of America minivan around Salt Lake City, looking for reclusive homeless people, those camping out next to the railroad tracks or down by the river or up in the foothills. The winter has been unseasonably warm so far-it’s 60 degrees today-but the cold weather is coming and the van is stacked with sleeping bags, warm coats, thermal underwear, socks, boots, hats, hand warmers, protein bars, nutrition drinks, canned goods. By the end of the day, Rene says, it will all be gone.

These supplies make life a little easier for people who live outside, but Rene’s main goal is to develop a relationship of trust with them, and act as a bridge to get them off the street. “I want to get them into homes,” Rene says. “I tell them, ‘I’m working for you. I want to get you out of the homeless situation.'”

And he does. He and all the other people who work with the homeless here have perhaps the best track record in the country. In the past nine years, Utah has decreased the number of homeless by 72 percent-largely by finding and building apartments where they can live, permanently, with no strings attached. It’s a program, or more accurately a philosophy, called Housing First.

One of the two phones on the dash starts ringing. “Outreach, this is Rene.” He’s upbeat, the voice you want to hear if you’re in trouble. “Do you want to meet at the motel? Or the 7-Eleven?” he asks. “Okay, we’ll be there in five minutes.”

Five days ago, William Miller, 63, was diagnosed with liver cancer at St. Mary’s Hospital in Reno, Nevada. The next day a friend put him on the train to Salt Lake City, hoping the Latter Day Saints Hospital might help. For the past two nights he’s been sleeping under a freeway viaduct. He vomits when he wakes up in the morning and has gone through two sets of clothes due to diarrhea. Yesterday he went to the LDS Hospital for a checkup and slept for five and a half hours in a bathroom. Now he’s sitting on the back of the van in a motel parking lot. A friend staying at the motel let him take a shower in his room, but then William started feeling weak, so he called Rene.

“I’m one that rarely gets sick,” he says. “It takes a lot to get me down, but I’m all out of everything.”

He has bushy sideburns and a lot of hair sticking out from a beanie and looks as if he was once much bigger than he is now, like he’s shrinking inside oversized clothes.

“I had two cups of Jell-O yesterday. My buddy got me a cup of coffee and a couple of doughnuts, but I’m gagging and throwing up everything. I’m nodding out talking to people, and that’s not good.”

Rene helps William get in the passenger seat and drives him to the Fourth Street Clinic, which provides free care for the homeless and is where Rene used to work as an AmeriCorps volunteer. He knows the system and trusts the doctors and nurses. William gets out of the van and walks inside very slowly and sits down in the waiting room. Rene checks him in. “I’m a tough old bird,” William says to me. “I ain’t never had something like this. I’m just weak as all get out, and in a lot of pain.”

Then he nods off.

The next stop is at a camp next to the railroad tracks. A 57-year-old man and a 41-year-old woman are living in a three-man dome tent covered with plastic tarps. Patrick says he’s doing okay, even though he’s had two strokes this year and has two tumors on his left lung and walks with a cane.

“My legs are going out. I’m sure it’s from camping out. We were living in the hills for two years,” he says. “My girlfriend, Charmaine, is talking about killing herself she’s in so much pain.” Charmaine is a heroin addict who suffers from diabetes, grand mal seizures, cirrhosis, and heart attacks. “When we lived in the foothills we both got bit by poisonous spiders,” she says, showing me a three-inch scar above her swollen right ankle. “The doctor tried to cut out the infection, but he accidently cut my calf muscle.”

She walks slowly, with a limp. As Rene is getting Charmaine in the van, Patrick takes him aside and asks if maybe Rene could get her into one of the subsidized apartments for chronically homeless people.

“If she comes back here she’ll die,” he says. “Especially with the cold weather coming.”

Rene tells him he’ll look into it.

On the way to the Fourth Street Clinic, I ask Charmaine how many times she’s been to an emergency room or clinic this year.

“More times than I can count,” she says.

By the end of the day, Rene has met with 12 homeless people, all with drug and alcohol problems, many requiring medical help, all needing the sleeping bags, warm clothes, food, and supplies that he hands out. As the sun sets we head back to the office with an empty van.

“I do it for the money and glamour,” he says, laughing. “No, I mean you cross a line and you really can’t go back, ’cause you just know this is out here.”

We could, as a country, look at the root causes of homelessness and try to fix them. One of the main causes is that a lot of people can’t afford a place to live. They don’t have enough money to pay rent, even for the cheapest dives available. Prices are rising, inventory is extremely tight, and the upshot is, as a new report by the Urban Institute finds, that there’s only 29 affordable units available for every 100 extremely low-income households.So we could create more jobs, redistribute the wealth, improve education, socialize health carebasically redesign our political and economic systems to make sure everybody can afford a roof over their heads.

Instead of this, we do one of two things: We stick our heads in the sand or try to find bandages for the symptoms. This story is about how Utah has found a third way.

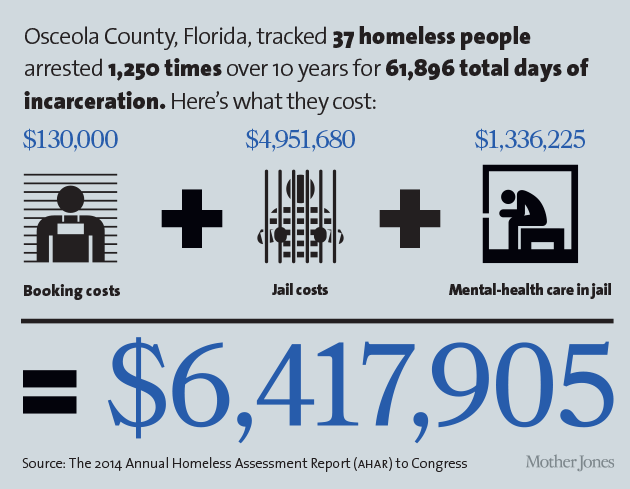

To understand how the state did that it helps to know that homeless-service advocates roughly divide their clients into two groups: those who will be homeless for only a few weeks or a couple of months, and those who are “chronically homeless,” meaning they have been without a place to live for more than a year, and have other problems-mental illness or substance abuse or other debilitating damage. The vast majority, 85 percent, of the nation’s estimated 580,000 homeless are of the temporary variety, mainly men but also women and whole families who spend relatively short periods of time sleeping in shelters or cars, then get their lives together and, despite an economy increasingly stacked against them, find a place to live, somehow. However, the remaining 15 percent, the chronically homeless, fill up the shelters night after night and spend a lot of time in emergency rooms and jails. This is expensive-costing between $30,000 and $50,000 per person per year according to the Interagency Council on Homelessness. And there are a few people in every city, like Reno’s infamous “Million-Dollar Murray,” who really bust the bank. So in recent years, both local and federal efforts to solve the homelessness epidemic have concentrated on the chronic population, currently about 84,000 nationwide.

In 2005, approximately 2,000 of these chronically homeless people lived in the state of Utah, mainly in and around Salt Lake City. Many different agencies and groups-governmental and nonprofit, charitable and religious-worked to get them back on their feet and off the streets. But the numbers and costs just kept going up.

The model for dealing with the chronically homeless at that time, both here and in most places across the nation, was to get them “ready” for housing by guiding them through drug rehabilitation programs or mental-health counseling, or both. If and when they stopped drinking or doing drugs or acting crazy, they were given heavily subsidized housing on the condition that they stay clean and relatively sane. This model, sometimes called “linear residential treatment” or “continuum of care,” seemed to be a good idea, but it didn’t work very well because relatively few chronically homeless people ever completed the work required to become “ready,” and those who did often could not stay clean or stop having mental episodes, so they lost their apartments and became homeless again.

In 1992, a psychologist at New York University named Sam Tsemberis decided to test a new model. His idea was to just give the chronically homeless a place to live, on a permanent basis, without making them pass any tests or attend any programs or fill out any forms.

“Okay,” Tsemberis recalls thinking, “they’re schizophrenic, alcoholic, traumatized, brain damaged. What if we don’t make them pass any tests or fill out any forms? They aren’t any good at that stuff. Inability to pass tests and fill out forms was a large part of how they ended up homeless in the first place. Why not just give them a place to live and offer them free counseling and therapy, health care, and let them decide if they want to participate? Why not treat chronically homeless people as human beings and members of our community who have a basic right to housing and health care?”

Tsemberis and his associates, a group called Pathways to Housing, ran a large test in which they provided apartments to 242 chronically homeless individuals, no questions asked. In their apartments they could drink, take drugs, and suffer mental breakdowns, as long as they didn’t hurt anyone or bother their neighbors. If they needed and wanted to go to rehab or detox, these services were provided. If they needed and wanted medical care, it was also provided. But it was up to the client to decide what services and care to participate in.

The results were remarkable. After five years, 88 percent of the clients were still in their apartments, and the cost of caring for them in their own homes was a little less than what it would have cost to take care of them on the street. A subsequent study of 4,679 New York City homeless with severe mental illness found that each cost an average of $40,449 a year in emergency room, shelter, and other expenses to the system, and that getting those individuals in supportive housing saved an average of $16,282. Soon other cities such as Seattle and Portland, Maine, as well as states like Rhode Island and Illinois, ran their own tests with similar results. Denver found that emergency-service costs alone went down 73 percent for people put in Housing First, for a savings of $31,545 per person; detox visits went down 82 percent, for an additional savings of $8,732. By 2003, Housing First had been embraced by the Bush administration.

Still, the new paradigm was slow to catch on. Old practices are sometimes hard to give up, even when they don’t work. When Housing First was initially proposed in Salt Lake City, some homeless advocates thought the new model would be a disaster. Also, it would be hard to sell the ultra-conservative Utah Legislature on giving free homes to drug addicts and alcoholics. And the Legislature would have to back the idea because even though most of the funding for new construction would come from the federal government, the state would have to pick up the balance and find ways to plan, build, and manage the new units. And where are you going to put them? Not in my backyard.

This is when two men who’d worked with the homeless in Utah for many years-Matt Minkevitch, executive director of the largest shelter in Salt Lake City, and Kerry Bate, executive director of the Housing Authority of the County of Salt Lake-started scheming.

“We got together and decided we needed Lloyd Pendleton,” Minkevitch said.

Pendleton was then an executive manager for the LDS Church Welfare Department, and he had a reputation for solving difficult managerial problems both in the United States and overseas. He’d also been involved in helping out with homeless projects in Salt Lake City, organizing volunteers, and donating food from the Bishop’s Storehouse. Dedicated to providing emergency and disaster assistance around the world as well as supplying basic material necessities to church members in need of assistance, the Church Welfare Department is like a large corporation in itself. It has 52 farms, 13 food-processing plants, and 135 storehouses. It also makes furniture like mattresses, tables, and dressers. If you’re a member of the church and you lose your job, your house, and all your money, you can go to your bishop and he’ll give you a place to live, some food, some money, and set you up with a job…no questions asked. All you have to do in return is some community service and try to follow the teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith. A system very much like Housing First-give them what they need, then work on their problems.

Minkevitch and Bate believed if they could get Pendleton to come on as the director of Utah’s Task Force on Homelessness he could mobilize the LDS, unite the different homeless-service providers, and sell the Housing First paradigm to the Legislature. Minkevitch’s agency had a close relationship with LDS leaders; the church had been a big donor for his shelter, The Road Home. Bate had worked with Lt. Gov. Olene Walker, who had just ascended to the governorship when Mike Leavitt was appointed to lead the Environmental Protection Agency. He asked her to write a letter to LDS elders, requesting that they “loan” Pendleton to the state. She did, and the church leaders said yes. It was a perfect marriage between church and state.

“The old model was well intentioned but misinformed. You actually need housing to achieve sobriety and stability, not the other way around.”

Once Pendleton took over the task force, he traveled to other cities to study their homeless programs. But he didn’t see anything he thought would work, at least in Utah. “I wasn’t willing to go to the Legislature until we could tell them we had a new goal and a new vision,” he said.

Then, in 2005, after a conference in Las Vegas, Pendleton shared an airport shuttle ride with Tsemberis and got a firsthand account of the Housing First trial. Tsemberis bore his testimony, as the Mormons would say, about the transformative power of giving someone a home.

“Going from homelessness into a home changes a person’s psychological identity from outcast to member of the community,” Tsemberis says. The old model “was well intentioned but misinformed. It is a long stairway that required sobriety and required stability in order to get into housing. So many people could never achieve that while on the street. You actually need housing to achieve sobriety and stability, not the other way around. But that was the system that was there. Some people called it a housing readiness industry, because all these programs were in business to improve people to get them ready for housing. Improve their character, improve their behavior, improve their moral standing. There is also this attitude about poor people, like somehow they brought this upon themselves by not behaving right.” By contrast, he adds, “Housing First provides a new sense of belonging that is reinforced in every interaction with new neighbors and other community members. We operate with the belief that housing is a basic right. Everyone on the streets deserves a home. He or she should not have to earn it, or prove they are ready or worthy.”

When I asked Pendleton if that struck a chord because Housing First seemed akin to the LDS Church Welfare Department, he was careful to insist that “the Mormon church is no different than other Christian churches in this way.” Whatever, he was sold.

Lloyd Pendleton is 74 years old, fit and spry with silver hair and pale-blue eyes that have the penetrating and somewhat mesmerizing stare of a border collie. He grew up relatively poor on a dairy farm and cattle ranch in a remote desert of western Utah and maybe has some cow dog in him.

“As a kid,” he says, “I was expected to do everything on the farm, from building fences to chopping wood to milking the cows. Every year I was given a new pair of work boots and a new pair of Levi’s. That was all my family could afford.”

He earned an MBA from Brigham Young University and was hired straight out of school by the Ford Motor Company in Dearborn, Michigan. “I remember my first day on the job, sitting at a table in the corporate headquarters, looking around and realizing everyone else had gone to Harvard or Yale, and I was just a country hick from Utah. It was intimidating, for sure, but I thought, ‘No one here can outwork me.'”

At Ford, Pendleton began to hone what he calls the “champion method” for getting results. Champions, according to Pendleton, have stamina, enthusiasm, a sense of humor, and they focus on solutions rather than process. Getting stuff done is more important than having meetings. A perfect meeting for Pendleton amounts to him clasping his hands and saying, “Let’s get going and not waste any more time.”

Pendleton asked Tsemberis to come speak to the state task force, which he did, twice. Then Pendleton called a meeting of “all the dogs in the fight” and announced that they were going to run a Housing First trial in Salt Lake City. He told them to come up with the names of 25 chronically homeless people, “the worst of the worst,” and they were going to give them apartments scattered around the city, no questions asked. If it worked for them, it would work for everybody.

“I didn’t want any ‘creaming,'” Pendleton said. “We needed to be able to trust the results.”

Many of the people in the room were uncomfortable with Pendleton’s idea. They were case managers and shelter directors and city housing officials who worked with “the worst of the worst” every day and knew they had serious personal problems-terrible alcoholism, dementia, paranoid schizophrenia. Something bad was sure to happen. There could be lawsuits. And who would be responsible? No, they thought, it will not work.

Pendleton, however, did not want to hear complaints. This was a small-scale trial, and he only wanted them to answer one question: “What do you need to get this done?”

So they did it. They ended up with 17 people and gave them apartments, health care, and services. They took people without a home and made them part of a neighborhood. And it worked, surprisingly well. After nearly two years, 14 were still in their apartments (the other three died), and they are still there today. They haven’t caused problems for themselves or their neighbors, Pendleton says.

Utah found that giving people supportive housing cost the system about half as much as leaving the homeless to live on the street.

The cost of housing and caring for the 17 people, over the first two years, was more than expected because many needed serious medical care and spent some time in hospitals. They were, however, the worst of the worst. Pendleton felt confident that, averaged out over the whole homeless population and over a period of years, they were looking at a break-even proposition or better-it would cost no more to house the homeless and treat them in their homes than it would to cover the cost of shelter stays, jail time, and emergency room visits if they were left on the street. And those “cashable” savings wouldn’t even include less quantifiable benefits for the rest of the state’s residents: reduced wait times at ERs, faster police response times, cleaner streets.

This is when Pendleton announced a 10-year plan to end chronic homelessness in Utah by 2015. But finding scattered-site housing wasn’t going to cut it. To house 2,000 chronically homeless people, they would build five new apartment complexes. Around 90 percent of the construction money would come from the Federal Low Income Housing Tax Credit program, which gives tax credits to large financial corporations that provide financing for housing authorities or nonprofits to build low-income housing-an average 6 percent profit on their investment. It’s a rather complicated and circuitous route, but it’s politically easier than getting lawmakers to allocate billions for poor people. The remaining 10 percent of construction costs would come from state taxes and charitable organizations. Most of the rent and maintenance on the units would come from federal Section 8 housing subsidies-and, at the time, Utah was fortunate enough not to have a long waiting list. On-site services, such as counseling, would largely be paid for by state and county general-fund dollars.

It took the task force only four years to build five new apartment buildings with units for 1,000 individuals and families. That, and an additional 500 scattered-site units, reduced the number of chronically homeless by almost three-quarters. And nine years into the 10-year plan to end chronic homelessness, Pendleton estimates that Utah’s Housing First program cost between $10,000 and $12,000 per person, about half of the $20,000 it cost to treat and care for homeless people on the street.

As anyone who’s followed social services can tell you, however, cheery annual reports can hide a world of dysfunction. So I go to see for myself.

Sunrise Metro was the first apartment complex built following the 2005 pilot study. It has 100 one-bedroom units for single residents, many of whom are veterans. Mark Eugene Hudgins is 58 years old and has brain damage. When I first start talking to him, I wonder if he’s been drinking.

“I always get hassled because I sound a little drunk,” he says. “My brain works a little slow. They drilled a hole in it.”

He had a motorcycle accident in Santa Ana, California, the year after graduating from high school. After that he spent 22 months in the Navy, then worked as a groundskeeper for the aerial field photography office of the Department of Agriculture for 13 or 14 years. He says he was homeless for five years before he came here, but he’s not sure: “My memory is a little fuzzy.”

“This is a nice place to live,” he says. “I put up with them and they put up with me, and it’s a good deal. I like it here.”

While we talk, two other residents come up to listen. One is in a wheelchair. His name is John Dahlsrud, 63, and he says he’s had MS for 45 years. The other guy looks like a weary Santa Claus-Paul Stephenson, 62, a Navy vet who lived for three years in the bushes behind a car dealership.

“The caseworkers are good,” Paul says. “They take us bowling on Saturdays. The apartment pays for one game, we pay for the second game.”

“They let you do what you want,” John adds, “as long as you keep things down to a minimum and don’t run up and down the halls naked.”

“Utilities are included, except for cable,” Paul says. “They gave everybody a free cellphone with 250 minutes a month. We get a pool table, a pingpong table, 60-inch television, eight recliner rockers. They give us food boxes once a month. I got 22 cans of tuna fish last month. There’s nothing to complain about.”

They each receive about $800 a month in Supplemental Security Income, and pay a third of that toward their rent. (The balance is paid via federal vouchers, along with some Utah funds.)

Over at Grace Mary Manor, I am given a tour by the county housing authority’s Kerry Bate-one of the men who helped persuade the LDS church to loan Pendleton to the task force. Grace Mary Manor is home to 84 formerly homeless individuals with disabling conditions such as brain damage, cancer, and dementia. You have to have a swipe card or get buzzed in at the front door, and there’s a front desk manager during the day and an off-duty sheriff at night. Bate explains that one of the biggest problems in giving homeless people a place to live is that they often want to bring their friends in off the street-they feel guilty. So there are rules to limit such visitations.

“It gives the people who live here a way out,” Bate says. “They can blame it on us.”

Tom Pinkerton, 67, from Red River, South Dakota, has cancer of the esophagus. He needs to have surgery, but first has to gain 10 to 20 pounds to make it through the anesthesia. (He has since passed away.) Howard Kelly, 44, from Denton, Texas, has brain damage from falling out of a car when he was a kid. David Simmons, 39, from Texas, was living under a bridge before coming here. I’m no doctor, but I’d guess he has some mental-health problems. Lorraine Levi says she’s “over 50.” Her boyfriend beat her up and broke her back. She needs surgery and is on strong doses of pain meds.

“The average person at Grace Mary was homeless for eight years before coming here, so their health condition is really poor,” Bate says.

On the third floor there’s a library with big leather chairs, nice wooden tables, and a portrait of Grace Mary Gallivan hanging above the fireplace. She died in 2000. Her father was a manager of a silver mine in Park City, and her husband was publisher of the Salt Lake Tribune. Her family foundation put up $600,000 for the construction of the apartment complex, matched by the foundation of the heirs to Utah’s first multimillionaire, David Eccles, who built one of the biggest banks in the West. From a window in the library you can look outside and see a gazebo for picnics and a volleyball court with evenly raked sand.

Bate introduces me to Steven Roach and Kay Luther, young caseworkers who check in on their clients every day to see what they need. They take them to the Fourth Street Clinic and Valley Mental Health, bring food from the food banks-pretty much anything they can do to help.

“The point is to have a service person on-site,” Bate says. “So if Sally Jo is having a crisis, we got somebody here who can help. Their goal isn’t to take everybody off the street and repair them and turn them into middle-class America. Their goal is to make sure they stay housed.”

“We have a guy who goes out to sleep in the park every month, and we have to go get him, talk him into coming back,” Roach says.

“There’s no mandate for participation in substance abuse or mental-health care, but we can certainly encourage it,” Luther says. “We had one guy who got completely clean from heroin and is off working in a furniture store.”

Bate shows me an empty apartment, a fairly spartan studio with linoleum floors, new sheets on the bed, the kitchen stocked with canned food, silverware, plates, etc.

“The church donated all of this,” Bate says. “Before we opened up, volunteers from the local Mormon ward came over and assembled all the furniture. It was overwhelming. For the first several years we were open, the LDS church made weekly food deliveries-everything from meat to butter and cheese. It wasn’t just dried beans-it was good stuff.” (The Utah Food Bank now makes weekly deliveries.)

I ask him if this is why the programs work so well in Utah-because of church donations.

“If the LDS church was not into it, the money would be missed, for sure,” he says, “but it’s church leadership that’s immensely important. If the word gets out that the church is behind something, it removes a lot of barriers.”

“Why do you think they do it?” I ask.

“Oh,” he says, “I think they believe all that stuff in the New Testament about helping the poor. That’s kind of crazy for a religion, I know, but I think they take it quite seriously.”

“Do you think you can meet the goal of eliminating chronic homelessness in Utah by 2015?” I ask.

“Yes,” Bate says, “we have a little less than 272 remaining unhoused, and that’s a number you can wrap your head around. Not like California and other places.”

“So do you think your success can be duplicated in other places?”

“I think it can be duplicated,” he replies. “San Francisco has Silicon Valley. Seattle has Bill Gates. Almost all of our larger cities have local philanthropic organizations that can help a lot with funding and building community support.”

And that’s the question, isn’t it? Can Housing First scale to areas where land and services are expensive, where NIMBYs are accordingly more powerful, places where the full organizational zeal and experience of the LDS church aren’t in evidence, and where data about the benefits of offering the homeless a permanent residence might not withstand the whims of politicians? In New York City, former Mayor Michael Bloomberg rolled out a well-regarded Housing First program focusing on mentally ill individuals. But he then gutted housing subsidies for the general homeless population, including families, after saying he thought they promoted passivity instead of “client responsibility.” Today, homelessness is the highest since the Great Depression, with 60,000 New Yorkers-including 26,000 children-on the streets, in the subway tunnels, and in the city’s sprawling network of 255 shelters, conveniently located far from the playgrounds of the 1 percent. “Every month I get a paper from Welfare saying how much they just paid for me and my two kids to stay in our one room in this shelter. $3,444! Every month!” one exasperated mom told The New Yorker. “Give me $900 and I’ll find me and my kids an apartment, I promise you.” The new mayor, Bill de Blasio, has pledged to reinvest in supportive and affordable housing, but 1 in 5 residents now live below the poverty line, and demand is high.

Former Mayor Michael Bloomberg slashed housing subsidies after saying he thought they promoted passivity instead of “client responsibility.” Today, 60,000 New Yorkers are homeless.

But the real test case might be California, where 20 percent of the nation’s homeless live. Los Angeles has 34,393 homeless people, more than a quarter of whom are chronically so. San Francisco has 6,408 homeless, Santa Clara County-home to San Jose and the greater Silicon Valley-has 7,567, and housing costs are among the highest in the nation. It takes three minimum-wage jobs to pay for an average one-bedroom apartment there. Tax credits for construction and Section 8 vouchers for rent don’t come close to the actual costs.

That’s the dilemma facing Jennifer Loving, the executive director of Destination: Home, a public-private partnership spearheading Santa Clara’s Housing First program. As in Utah, the leaders of Santa Clara’s initiative were able to marshal different agencies, nonprofits, and private groups, unifying their vision and goals to house the chronically homeless. “At first, it was tough to move out of the shelter way of doing things. It was new to all sit around the same table and change the way the system responds to homelessness,” Loving says.

Like Pendleton, they addressed the chronically homeless cases first. In 2011, in conjunction with a national effort called 100,000 Homes, they began a trial to house 1,000 people who’d been homeless for an average of 18 years and estimated to cost the system upward of $60,000 a year. “Our motto was, ‘Whatever it takes,'” Loving says. “We built the plane as we were flying it.” That meant lots of innovation along the way, such as creating a $100,000 flex fund to do things like pay off small dings on people’s credit, so they could qualify for vouchers and establish rental history: “So if Bob has an eight-year-old violation on his credit history, we’d just pay that off,” Loving says.

By the end of 2014, they had housed 840 people in apartments scattered around the county. The remaining 100 or so have rental subsidies but can’t find a place to live due to exceptionally high occupancy rates. Still, the trial was considered a big success-in part because supported housing only cost an estimated $25,000 per person-and Santa Clara County has now officially adopted the Housing First model. “We made a system out of nothing, and we used it like an assembly line to house people,” Loving says. “And the only thing in our way is the high cost of housing stock.”

So now they’re embarking on a five-year plan to house the county’s remaining 6,000 homeless. First, they’ve launched an extensive study on exactly how much homelessness actually costs taxpayers. Those costs are very hard to determine: There are so many agencies involved-hospitals, jails, police, detox centers, mental-health clinics, shelters, service providers-and they all keep separate records, separate sets of data used for separate purposes, all run on separate pieces of software. “Each department has an information system and a team that looks at the data,” says Ky Le, director of the Office of Supportive Housing for Santa Clara. “They have small teams who know their data best, how it’s configured and why, what’s accurate and what’s not.” Ky says that merging datasets has been “a tremendous effort,” but by integrating and analyzing it, Santa Clara hopes to better understand who’s already a “frequent flier” of clinics and jails, and, more tantalizingly, to develop an early warning system for who is likely to become one, and how they can be housed and cared for in the most cost-effective manner.

New housing needs to be found, or built, but with the market so tight, finding housing-any housing-is a huge challenge, one made worse when Gov. Jerry Brown slashed all $1.7 billion of the state’s redevelopment funds during the 2011 budget crisis. (Those funds have not rematerialized now that California has a huge budget surplus.) So they’re getting creative-“tiny homes, pod housing, stackable-we’re looking at it all,” Loving says. And they’re employing creative financing efforts, like “pay-for-success” bonds, in which investors (mostly foundations) would stake the construction funds and get a small return if the savings materialize for the county.

Advocates estimate it could take up to a billion dollars, half from grants and philanthropy, the other half in the form of county land and services. “The work we’re going to be doing in the next year,” Loving says, “is determining where and how to create new units and how much they are going to cost and where we can get the resources from-whether it’s private or public money. The money is all here. We have eBay, Adobe, Applied Materials, Google.” The hope is that the emphasis on quantified efficiency will persuade tech firms and billionaires obsessed with metrics that Housing First is a solid civic investment. “It’s fascinating because we have this problem we could totally solve if we wanted to,” Loving says. “We solve complicated problems all the time, right? Silicon Valley is an example of solving complicated problems all the time.”

If places as different-economically, demographically, politically-as Salt Lake City and Santa Clara County can make Housing First work, is there any place that can’t? To be sure, the return on investment will vary, depending on how you count the various benefits of fewer people living in the streets, clogging emergency rooms, and crowding jails. But the overall equation is clear: “Ironically, ending homelessness is actually cheaper than continuing to treat the problem. This would not only benefit the people who are homeless; it would be healing for the rest of us to live in a more compassionate and just nation,” Tsemberis says. “It’s not a matter of whether we know how to fix the problem. Homelessness is not a disease like cancer or Alzheimer’s where we don’t yet have a cure. We have the cure for homelessness-it’s housing. What we lack is political will.”

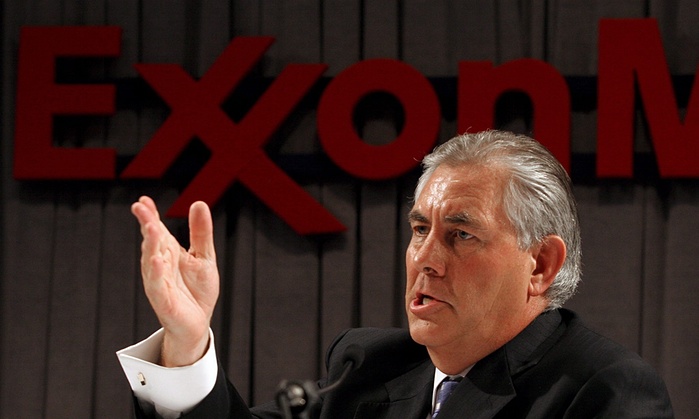

Fat cat pay at fossil fuel companies drives climate crisis – report

Executive pay at fossil fuel companies rewards corporate behavior that deepens the climate crisis, and offers no incentive to shift towards renewable energy, a Washington thinktank said on Wednesday.

Executives at the 30 biggest publicly held coal, oil and gas companies in the US were paid more than leaders of other major corporations, about 9% higher than the S&P 500 average, the Institute for Policy Studies (IPS) found.

The big pay days extended across the industry to executives of coal companies whose share prices have gone into free fall last year.

The report, “Money to Burn: How CEO pay is accelerating climate change”, argued that such out-size pay packages – inflated by bonuses for expanding reserves – encouraged executives to hunt for oil, coal and gas even though those new fuel sources can not be tapped without triggering dangerous climate change.

“It seems to me executives are rewarded no matter what is happening with the planet – and even within their own companies,” said Sarah Anderson, director of the IPS global economy project and co-author of the report. “Executives are still being rewarded specifically for expanding carbon reserves at a time when scientists say we are already sitting on too much.”

Shareholder activists have long been pressing for companies to change their corporate behavior – including compensation packages.

“The bottom line is that breaking the link between executive compensation and chasing ever-more expensive barrels of oil is key to transforming the industry,” said Shanna Cleveland, who heads the carbon asset risk programme at Ceres, the green investment network.

In the case of fossil fuel companies, one of the main factors for calculating bonuses was based on executives’ success in expanding fuel reserves. Last year saw oil, coal and gas company executives cashing in.

Chief executives of fossil fuel companies took home an average $14.7m (£9.6m) last year, about 9% higher than the average $13.4m for S&P 500 chief executives.

The chief executives of ExxonMobil and ConocoPhillips, the two biggest publicly held companies, made more than twice the S&P average last year, the report said. Rex Tillerson, Exxon’s chief executive, took home $33m last year. Ryan Lance, the chief executive of ConocoPhillips and the second-highest paid leader of a big oil company, took home $27m.

More than half of their compensation packages came in the form of stock options and stock grants which vest over three to four years. Climate change plays out over decades, however.

Current pay packages encourage executives to lobby against attempts to end fossil fuel subsidies, or advance clean energy regulations, the thinktank said.

None of the 30 top fossil fuel companies encourage moves to cleaner energy. Campaigners said that needed to change.

“If we are serious about climate change then we need to start incentivising the kind of behavior we need to see,” said Laura Berry, director of the Interfaith Center on Corporate Responsibility. “Until we get a real change in corporate strategy which will not happen without properly aligned incentives, we are not going to see the magnitude of change needed to turn things around.”

Thousands of Icelanders Have Volunteered to Take Syrian Refugees Into Their Homes