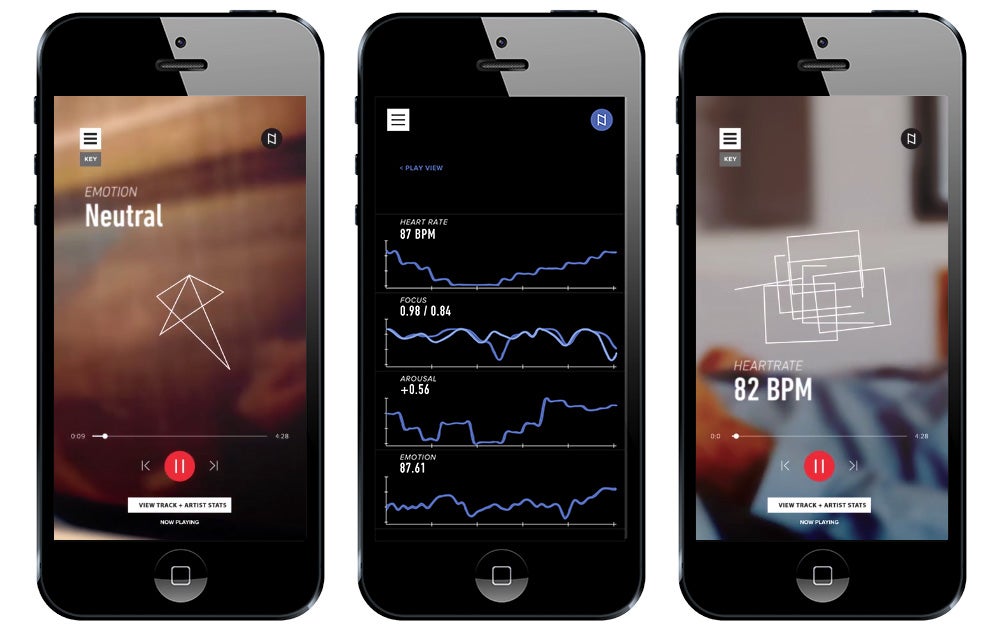

Festival-goers at this year’s SXSW saw their share of product demos, including one for The Sync Project. The venture, backed by Boston-based startup creator PureTech,overlays biometric data and predictive technology to better understand music’s impact on the body and the brain. Through wearables, the technology acts as a sort of FitBit / Spotify hybrid, tracking everything from arousal to heartbeat to focus.

By decoding how songs influence our brains and bodies, The Sync Project’s goal is to harness music to improve health. Music can be a science, as formulaic pop hits demonstrate. And with songs already pumping us up at the gym or soothing us after a bad day, it’s not a stretch to envision a world where artists like Taylor Swift or One Direction craft tunes to treat Alzheimer’s, anxiety or even autism. “We want to scientifically design therapies for different conditions,” says Alex Kopikis, one of the company’s co-founders.

But while the next Snapchat can arrive overnight, biotech companies must cycle through rounds of clinical trials and navigate rigorous regulatory landmines. So, despite its March unveiling, The Sync Project’s solutions are still likely years away. Unpredictable timeframes highlight the challenges facing biotech companies competing for buzz alongside traditional tech startups, and the creative ways they are maintaining momentum.

Listening as medicine

The Sync Project believes song data could shape users’ physiology and mood, by anticipating how listeners’ bodies and brains respond to musical elements. “Every note has information in it,” says Tristan Jehan, an advisor to The Sync Project. His audio fingerprinting service was acquired by Spotify last year and builds recommendation algorithms to decipher the similarities between genres, artists and songs.

Image Credit: The Sync Project

But for companies looking to harness that data, a lot remains unproven. “The problem with music and medicine is that everyone wishes that music is beneficial and that it is an easy fix,” says Nadine Gaab, an assistant professor of pediatrics at the Boston Children’s Hospital /Harvard Medical School. “If you really go hardcore down to the evidence, there isn’t much.”

Related: Researchers Are Using Yelp to Predict When a Restaurant Will Shut Down

While a large body of research ties music to physiological benefits like boosting cognition in dementia patients or improving verbal abilities in autistic children, some experts believe most of these studies would not withstand rigorous evaluation. Many studies linking music and health “are not completely well-designed,” says Ketki Karanam, a Harvard-educated biologist and a co-founder at The Sync Project.

Not all music therapists are trained for experimental work and studies often suffer from small sample sizes, mismanaged control groups and a reliance on subjective feedback. “It’s pretty sad how few of these studies are well executed, controlled randomized trials,” says Gaab.

“People have a tendency to oversimplify things,” adds Robert Zatorre, a neurologist at McGill University and a scientific advisor to the company. It’s natural for us to be drawn to “a sexy story,” he explains, even if the reality is less immediate.

Competing for dollars and buzz

Biotech offers its own challenges to innovators. While software solutions can launch in days or months, proper scientific testing can push biotech launches far into the distance. Alkili, another PureTech venture, was announced in 2012 but might not come to market until 2016 or later. Says Eddie Martucci, Akili’s co-founder, its progress rate still beats most scientific advances. “Usually when you hear about an innovation in the medical world, you hope that your kids can tap into that. So if the timeline is a couple years? That’s amazing.”

Unpredictable timing can dampen funding, however. Venture capital backing for biotech and pharma dropped 50 percent between 2010 and 2015, according to PitchBook, a Seattle-based data provider on private markets. This drop came, PitchBook says, because biotech projects can “take longer to successfully build, hurting returns.”

Related: Google to Break Ground on Life-Prolonging Research Facility

Investors familiar with health and biotech see long timelines as a protective barrier against competition, says Sam Sia, a faculty member in biomedical engineering at Columbia University and the founder of Harlem Biospace, a biotech incubator in New York City. Still, traditional tech investors new to the space “may be discouraged that the process takes longer than they’d hoped.”

Biotech also competes for attention with companies that don’t need scientific backing. Recently more than 70 prominent psychologists, cognitive scientists and neuroscientists wrote an open letter to companies making certain brain training software that the researchers felt exploited seniors’ anxieties about cognitive declines and made “exaggerated and misleading claims.”

“There are a lot of companies marketing products, making claims that we wouldn’t be comfortable with,” says Daphne Zohar, PureTech’s founder, CEO and managing partner. “Before putting a product on the market, Pure Tech’s strategy is to first put it through rigorous testing, the same process if this was a medical device or a drug.”

This summer PureTech raised $171 million in its initial public offering on the London stock exchange. That money, along with the $100 million the company raised in funding earlier this year, will be reinvested into its portfolio of individual companies, allowing them to launch at their own pace, says Zohar.

While many of Pure Tech’s investors focus on healthcare, and are familiar with the often long road to clinical validation, a large percentage are traditional tech investors. Which makes sense, as Pure Tech straddles both sectors. “This is a new industry, so it’s not going to be exactly like tech and it’s not going to be exactly like traditional biotech,” says Zohar. “The timelines to market will be shorter than traditional biotech, but the things we are doing take longer than just putting a product out on the market.”

Walking the line

Leading a buzzy, disruptive biotech company without running afoul of the FDA means walking a tricky tightrope. When personal genomics service 23andMe launched in 2008, it blazed trails and helped merge the tech and biotech world, says Sia.

Related: Meet Color Genomics, the Startup That Wants to Make Genetic Testing Less Expensive

But the FDA shut down much of its testing operation in 2013. And so the company was forced to split its strategy to focus mostly on ancestry reports, a consumer product that made no medical claims, while it worked with regulators. The approach, while slow-going, got results. It received approval for a Bloom syndrome test this past February.

Companies like The Sync Project will need to strike a similar balance. Until its full launch, the company is strengthening its role as a thought leader in music and tech, leveraging the expertise of its advisors from MIT and Spotify. In July, the company hosted a workshop in Montreal at McGill University, inviting researchers in music, neuroscience, psychology and medicine to discuss the state of technology in current research on music’s impact on the mind and body. A new partnership with Berklee College of Music in Boston will include collaborative research efforts, joint-course development, and an internship program for music therapy students between the school and The Sync Project.

In the meantime, the company is building a special research platform to facilitate rigorous, well-designed clinical trials, run by independent researchers, to determine whether or not music has a palliative effect on a host of conditions and diseases. Most of the data the company collects will be accessible to researchers, says Ahtisaari, although the company is still developing a system in which this information can be shared.

These trials, which use The Sync Project’s app, are slated to begin this month. In addition, the company wants to conduct large-scale, open studies, in which anyone who wants to participate can download the app, track how songs impact their biometric data and answer a few survey questions, says Marko Ahtisaari , The Sync Project’s recently appointed CEO and former head of design at Nokia. This hybrid approach — collecting large amounts data in conjunction with smaller data sets from clinical trials — will not only facilitate a more diverse and rigorous test sample, but also likely accelerate the app’s time to market, says Ahtisaari.

“Our key motivation is to enable researchers to design and carry out better studies that will identify music’s potential,” says Karanam.

While such measures aren’t perfect, they’re a start. “These things do take quite a bit of time,” says Zatorre. “You have to do things carefully.”

Related: Are You an Empathetic or Analytical Thinker? Your Music Playlist May Hold the Answer.