From frustrated snowboarders to migrating birds arriving at shriveled wetlands to wildfires raging through national parks, the Sierra Nevada’s lack of snow has transformed just about every aspect of life in California. Farmers, fish, forests, gardeners, hikers, boaters, and more depend on Sierra snow for water.

But now it’s clear that the “snow fail” in the 400-mile long mountain range has reached epic proportions: This year’s snowpack is the driest it’s been in at least 500 years, according to new research published Monday.

This stark finding comes from an analysis of more than 1,500 California blue oak tree rings dating back to the early 1500s, when Spanish explorers were just beginning their conquest of the state.

Researchers who examined cores from the long-lived oaks to calculate the water content of each year’s snowpack were stunned to find that no other year was even close to as dry as 2015. Temperature data show why: The state was slammed with a drought-and-heat double whammy.

“What happened in 2015 is that very low precipitation co-occurred with record high temperatures. And that’s what made this snowpack low so extremely low,” says Valerie Trouet, a tree-ring research specialist at the University of Arizona in Tucson and co-author of the study published in Nature Climate Change.

The researchers had expected the 2015 results to be bad, ‘but we didn’t expect it to be this bad,’ Trouet says.

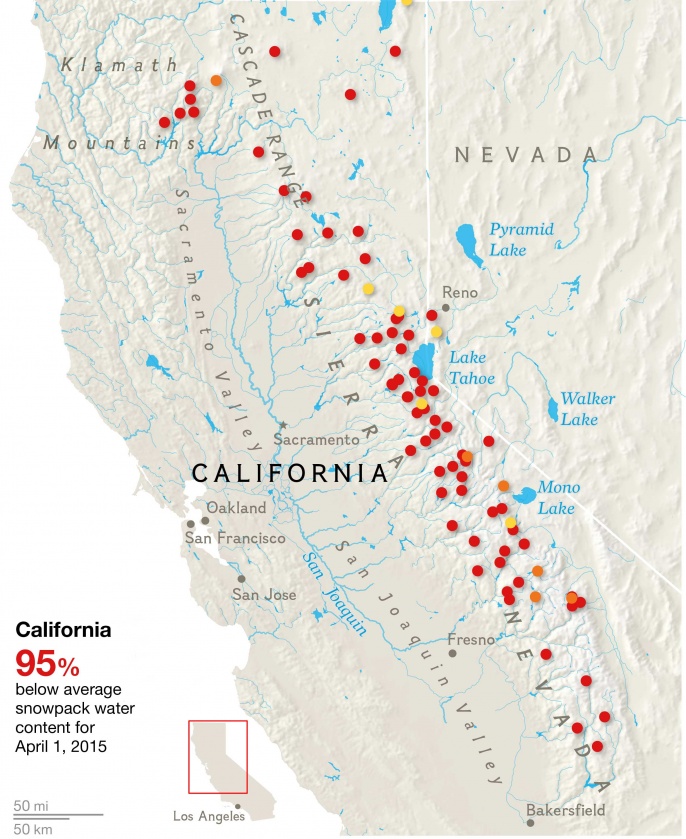

The 2015 Sierra snow water equivalent, a measure of water content, was just 5 percent of average over the past half-millennium, the researchers found. The next-closest lows were 2014 and 1977; both years the water content was 25 percent of average.

The team, which also included scientists from the National Atmospheric and Oceanic Administration in Colorado and the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville, calculated snow water content from the width of the tree rings. California blue oaks are “really really reliable recorders of the amount of rainfall that falls in the winter season,” Trouet says, because they produce wide rings after wet winters.

The researchers had expected the 2015 results to be bad, “but we didn’t expect it to be this bad,” Trouet says.

In fact, the water content of the Sierra Nevada snowpack could actually be at its lowest in 3,100 years, she said, based on a different analysis also reported in the study. That statistical method has a higher margin of error, but confirms that the 2015 snowpack is off-the-charts.

The result has been a summer of steep water cuts and exploding wildfires, billions in economic damage, and stressed wildlife-and perhaps a preview of what’s to come under climate change.

“Snow Melting Into Music”

Stretching from the grapevine snaking into Los Angeles to forests about 300 miles shy of the California-Oregon border, the Sierra Nevada’s reach encompasses Yosemite’s waterfalls, Lake Tahoe (the largest alpine lake in North America), Mount Whitney (the highest peak in the lower 48 states, and other renowned landscapes. Naturalist John Muir called them the Range of Lights and wrote “the snow is melting into music” to describe the voluminous fresh water running off its peaks.

Their snowpack is crucial to water supplies throughout California, including semi-arid Los Angeles and other southern cities, the San Francisco Bay Area, and Central Valley farms.

The storied Sierra snow is normally so saturated that skiers and snowboarders call the heavy powder “Sierra Cement.” This dense icing slowly melts into rivers and streams throughout the spring and summer; feeding reservoirs, flooding wetlands, and refilling the water table. (Read more here in National Geographic Magazine’s When the Snows Fail.)

For those who grappled daily with last winter’s scant snows, the centuries-long record may come as a surprise, but its severe effects do not.

“The past season’s suspension of operations was certainly the earliest on record, which doesn’t come as a surprise, given the [new findings of a] 500-year low of snowpack in the Sierra,” Thea Hardy, spokeswoman for the Sierra-at-Tahoe ski resort near South Lake Tahoe, said in an email.

Week after week it just kept not snowing and it was getting hotter and hotter.

The 2,000-acre resort, which has often stayed open into May during its nearly 70 years in business, shut down in mid-March. It was one of many California winter recreation spots that closed far earlier than usual this year.

Much of the precipitation that did fall last winter came down as rain, at lower elevations.

Ski instructor Sophie Castleton experienced that problem first-hand.

“Week after week it just kept not snowing and it was getting hotter and hotter,” says Castleton, who worked last winter at Alpine Meadows, near the California-Nevada border town of Truckee. “A lot of times it looked like it would snow, but then it would turn to rain and there would be puddles around the lifts.” That resort also closed early, and Castleton felt bad for her several colleagues who had come from South America and Australia to work.

Water managers are also keenly aware of the epic snow fail. The California Water Project, which oversees 154 reservoirs in the state, is able to deliver only 20 percent of the water its customers request, says Doug Carlson, information officer for the Department of Water Resources.

Californians have cut their water use by a whopping 31 percent and are for the most part getting by this summer with short showers, yellow lawns, and infrequently flushed toilets. (Read here what drought veterans say about this four-year dry spell].

Stressed Wildlife and Raging Wildfires

Wildlife is far less flexible, complicating management, Carlson says. Native salmon fry, for instance, need cool water to survive. Water in dwindling reservoirs heats up more quickly, which can be deadly to the young fish.

The lack of snowpack could turn California’s summer and fall wildfire season into a year-round event. Unseasonal winter blazes, such as last February’s fire near Bishop, are now torching Sierra elevations that used to be blanketed with snow. The 2015 statewide wildfire count is up more than 1,500 over last year, with a huge one now threatening Kings Canyon, home to the giant sequoias that are among the oldest living things on the planet.

No sure reinforcements for the snowpack are in sight. Predictions of a major El Niño event this winter likely mean heavy rains in Southern California, but the outlook for the Sierra and its indispensable snowpack are uncertain.

The drought probably will keep coming back as global temperatures climb, Trouet and other scientists say.

A new report by the Public Policy Institute of California’s Water Policy Center gives a glimpse of the toll: At least 18 species of native California fish, including salmon and steelhead trout, face imminent extinction if current conditions continue another two or three years. The 5 million birds migrating along the Pacific Flyway annually risk starvation and disease. Cities will fare better, but strict conservation will have to become a permanent way of life. Farm losses could top $2.8 billion a year.

A grim prospect. But Hardy, like many Californians, say they’ll adapt.

“We’ve learned that adapting to the effects of light snow years is just as important as riding out long, fruitful seasons,” the ski resort spokeswoman says. Whatever happens, she says, “we plan on taking advantage of every inch of snow that we receive.”