What We Can Learn from San Francisco: Mandatory Composting and Zero Waste

I recently visited San Francisco, California-what an incredible city! With its diverse blend of cultures, beautiful vistas, and incredible food, what’s not to love?

The people living and working in San Francisco demonstrate a clear dedication to helping the environment. Public transportation is quite popular with people from all economic levels. Vegan and vegetarian restaurants abound. Every Sunday, there is a farmer’s market that stretches for blocks and blocks, offering organic produce for lower prices than I pay for conventionally-grown produce back home in Maryland.

But what struck me the most on my visit was that composting has been fully accepted into the mainstream culture. Everyone participates in composting. This is because the city has made it easy and convenient to do so.

Food waste is a critical issue with a serious impact on the planet. Composting is a great way to reduce waste and help the environment. When you compost, you save all the plant matter (such as lettuce ends, orange peels, etc.) and other organic matter (think eggshells, food-soiled cardboard) from going into the trash/landfill. This organic matter is then collected and broken down by microorganisms, which are found naturally in soil. The end result is a fiber-rich material called humus which can be used as all-natural, organic fertilizer for gardens or farms.

A Model City

The city of San Francisco provides recycling and composting bins to all households and businesses. This is not just curbside recycling, but also curbside compost pickup! I was thoroughly impressed. Actually, it’s mandatory under the San Francisco Mandatory Recycling and Composting Ordinance, passed in 2009. This was “the first local municipal ordinance in the United States to universally require source separation of all organic material, including food residuals.”

Recology is the company that handles the collection of the organic waste, and passes it along to composting facilities such as Jepson Prairie Organics. These facilities then sell the processed compost to everyone from small-scale residential gardeners to huge farms and Napa Valley wineries. So instead of the waste piling up in a landfill, it is returned to the Earth and utilized to grow new food for people to enjoy-just as nature intended.

In 2011, San Francisco was composting a record 600 tons of organic matter per day. This is far more than any other U.S. city and surpasses almost all cities globally.

It’s About More than Just the Trash

There is also an impactful social element at work. Just by virtue of being a San Francisco resident, you automatically become an active participant in a helping the environment. This creates a pervasive culture of environmental awareness. By taking this first step and seeing the difference they can make in their everyday lives, people are undoubtedly encouraged to take further action for the Earth, such as using public transportation or switching to a plant-based diet, just for starters.

Also, when composting is an accepted daily practice, other steps to facilitate its success become ingrained in the local businesses and culture. For example, San Francisco restaurants offering take-out provide the food in fully compostable containers, so the whole thing including any leftover food particles can go straight into the compost bin. This simple step simultaneously makes composting easier for the consumer and reduces waste.

The city has recently passed ordinances to ban polystyrene food containers, plastic water bottles, and plastic bags. Fees and penalties have been implemented for those who continue to use or sell these materials. These regulations further reduce the amount of materials that go to the landfill, and also prevent plastics and styrofoam from polluting California’s waterways and beaches.

Back to Reality

Needless to say, when I returned home to Maryland, I was disappointed and even felt quite guilty about throwing away all of the organic matter that, while in San Francisco, I had been easily and conveniently able to compost. (I will be starting my own household composting project very soon-but that’s a story for another blog post!).

So I started doing some research, to find out how likely it was that I could convince my local government to offer curbside composting in my own town. I wondered, with all the benefits, why doesn’t every city or town offer services to make composting convenient?

The major obstacle for municipalities everywhere is the cost: Startup and education costs, ongoing costs associated with waste pickup and maintenance of the program, and the challenge of changing the existing infrastructure to implement a program and facilities that will be effective and efficient enough to keep costs down year over year.

In many towns and cities that do offer some form of composting, the focus is on yard trimmings. About 70% of composting operations are solely for yard waste, according to a 2014 study. Composting on site at farms and agricultural institutions was the next largest segment at 8%, and food scraps made up 7%. Data in the study included reports from composting operations in 44 out of the 50 U.S. states.

When you look at total volume of organic material processed per year, 72% of composting facilities are composting less than 5,000 tons of materials annually. Only 7% of them composted 20,000 tons or more.

In the U.S., San Francisco is the recycling and composting leader. As of 2013, San Francisco was recycling or composting 80% of its waste. By comparison, Los Angeles recycles or composts about 65% of its waste and Seattle about 50%. Portland, OR, Boulder, CO, Austin, TX, and other cities offer curbside recycling and composting. New York City diverts only 15% of its waste to recycling, and does not yet have a composting program, although it is planning to begin composting food waste. In the U.S. overall in 2012, according to the EPA, about 34% of waste was recycled and of that, only 3% was composted.

Internationally, the European Union was recycling or composting about 42% of its waste as of the end of 2013. Copenhagen, one of the greenest cities in the world, stopped sending organic waste to landfills as far back as 1990 and plans to be carbon neutral by 2025.

What Other Cities and Towns Can Learn from the San Francisco Success Story

It’s all about convenience and education. San Francisco’s “Fantastic Three” bins (black for landfill, blue for recycle, green for compost) make it easy for people to make a conscious choice about where to put their trash each time they go to toss it. The city has spent significant time and money educating their residents about what can go into each bin, how to keep the compost from getting smelly, what to do with non-recyclable materials, and other important tips. Their website is user-friendly and informative. San Francisco has done a great job addressing all the main objections that resistant residents might raise.

The mandatory ordinance is key. It leaves no room for lax attitudes about recycling and composting. But the city even upped that ante by creating a Zero Waste by 2020 commitment. By the year 2020, the city plans to send nothing to landfill or incineration. All signs indicate that their dedication to this goal will reach success.

Offsetting the costs of the waste collection is a crucial step. The SF Zero Waste program is funded fully from refuse rates charged to customers (about $34 per residence per month in 2013, with a discount if you switch to a smaller black “landfill” bin). This covers outreach and marketing materials, and some government program costs. The cost of collecting from the Fantastic Three bins are entirely offset by selling the recyclables and the compost.

A blind man and his armless companion plant over 10,000 trees in China

Jia Haixia and Jia Wenqi are 53 year-old men with disabilities. Mr. Haixia is blind and Mr. Wenqi has had his both arms amputated. Despite their disabilities, they form a great team that makes a huge difference. They have worked together for 10 years and have managed to plant 10,000 trees in a rural area in Hebei, China. They deserve to be called eco-warriors and heroes for their incredible efforts and amazing deed!

10 years ago, these men decided to team up and start their work together. This happened after they both couldn’t find jobs due to their physical incapability. Happily, they have managed to think of a unique way to pair up and make a difference. ‘I am his hands and he is my eyes,’ says Mr. Haixia. With each other’s help, they succeeded in transforming a three-hectare stretch of riverbank, despite the intensive and hard work planting trees requires.

Mr. Wenqi is a 53-year old man who had lost his both arms when he was only a 3-year old. Mr. Haixa is also 53 and was born with an eyesight problem. His condition is called congenital cataracts which affected his sight with his left eye, leaving it blind. Sadly, he lost sight with his right eye as well in a work accident. Both men’s unfortunate disabilities deprived them from finding secure jobs later in their lives. This is why in 2001 the eco-warriors leased from the government a large portion of a riverbank in a bid to plant trees for the generations to come. Plus, this action would contribute to the protection of their village from floods. Hoping for a modest income, they devoted their days to their work. They both leave their home at 7:00 in the morning carrying a hammer and an iron rod. But in order to start with their work, they have to pass through a river in order to get to the other side of it. To do this, Mr. Wenqi has to carry his blind friend every day.

Their working process is really interesting. As they don’t have enough money for saplings, they have to collect the cuttings which is not a simple task. They have come up with a unique and efficient technique that helps them optimize their work. As Mr. Haixa is the one who has to scale the trees, he climbs on his armless partners’ shoulders and guides him while he pulls himself through the tree branches. After climbing down, he digs a hole in the ground and plants the new cutting in the soil. It is Mr. Wenqi who takes care of the new saplings by watering them. Doing this for 10 years has resulted in the land being covered in thousands of new trees that attract a significant number of birds.

‘Though we did not accomplish much in a dozen years, we recognize our effort,’ says Mr. Haixia. Mr. Wenqi adds: ‘We stand on our own feet. The fruits of our labor taste sweeter. Even though we are gnawing on steam buns, we find peace in our hearts.’

Marley Protecting Jamaica’s Rasta Villages

Donisha Prendergast and other supporters are occupying a tabernacle – a Rastafarian place of worship – near the village established by Leonard P Howell in the 1930s, according to the Jamaica Gleaner.

The campaign wants the property – a hilltop called The Pinnacle west of the capital, Kingston – to belong to the Howell family and the community.

No black person in Jamaica owned property, nothing compared to Pinnacle

Prendergast told the newspaper: “We are not going anywhere, one by one we are filing in, we are going to camp out and reason.”

It appears that the Rastafarian community may have no title to the land, but they claim they are entitled to use it due to their historical and cultural connection to the site.

A quarter-acre plot on The Pinnacle has been declared a national monument, the Jamaica Observer says. But the campaign is calling for the whole area to be preserved.

The dispute over ownership on The Pinnacle has been the subject of long-running controversy, with Howell’s descendants fighting court cases against local developers.

Howell’s son, Monty, says papers proving the family’s ownership of the land were destroyed during the 1930s and 1940s because the island’s then-colonial authorities thought it “presumptuous” for Howell to own it.

“No black person in Jamaica owned property, nothing compared to Pinnacle,” he told the Jamaica Observer. “They tried everything to chase my father off that land.”

The case is heading back to the courts in Jamaica this week. (3 February 2014)

75 Percent of Animal Species to be Wiped Out in ‘Sixth Mass Extinction’

Under the most conservative estimate possible, development, disappearing habitats and climate change will exterminate animal species within just three human lifetimes, a new study finds.

An elephant killed by poachers lies among the grass in Mozambique. The species is among those threatened with extinction in the next three human lifetimes, a new study finds.

From rhinos to tigers to elephants, three out of four “familiar” animal species – those commonly thought of and well understood by human beings – will be extinguished within three human lifetimes, a new study finds, confirming that Earth is in the midst of what’s become known as the “sixth mass extinction” driven by runaway development, shrinking animal habitats and climate change.

“Scientists never like to say anything for sure, but this is close as we’re ever going to get to saying, ‘We’re certain that this is a huge problem,'” says study coauthor Anthony Barnosky, a paleontologist at the University of California-Berkeley, calling the problem “quite dire.”

[ READ: Pope Francis Encyclical Calls on “All Humanity” to Halt Global Warming]

The hundreds of species eliminated in the past century alone would otherwise have lasted at least another 800 to 10,000 years, the study found. Coral reefs “are in danger of annihilation” as soon as 2070, Barnosky says, potentially erasing a quarter of the ocean’s species.

The last mass extinction occurred 66 million years ago with the end of the dinosaurs. This is the only one, however, where a single species is responsible for the destruction of all the others. And by eliminating biodiversity, it threatens to disrupt the pollination, water purification, food chain and other “ecosystem services” that humanity’s “beautiful, fascinating and culturally important living companions” provide, the study says – threatening human life itself.

“You can kind of think of it as guns and bullets,” Barnosky says. “The guns are different in each case, but the bullets that come out – changing climate, increased CO2 and other gases in the atmosphere, ocean acidification – those things that contribute to mass extinction are the things that we’re doing today.”

Previous studies had established the world is in the midst of a mass extinction, with animals disappearing at far faster rates than expected. The term even made the title of New Yorker writer Elizabeth Kolbert’s 2014 bestseller, “The Sixth Extinction.” There is no way to know just how many species there are on earth – roughly 1.3 million animals have been described since 1758. A study last September, however, found the number of wild animals had likely been halved in just the past 40 years.

[ ALSO: Why an “Inadequate” Climate Agreement Might Be OK – Or Not]

But this latest effort is by far the most conservative: a study aimed at debunking any possible rebuttal that its findings are “alarmist.”

Barnosky and his team, hailing from Florida and Mexico as well as California, doubled the pace that species were expected to go extinct without any human interference, then used the lowest possible estimate for the number of species that actually were disappearing.

The results, even as an underestimate, proved just as dire.

Since 1900, birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians and fish died 72 times faster than “normal,” this most conservative estimate found. Whereas researchers might have expected nine veterbrates to go extinct, instead 468 were wiped from the Earth.

Industrialization was especially lethal, with extermination rapidly accelerating from 1800 on.

“The most iconic bird species historically are gone – the ivory-billed woodpecker, passenger pigeon, Carolina parakeet, great auk, imperial woodpecker,” says study coauthor Paul Ehrlich, professor and president of the Center for Conservation Biology at Stanford University. “But there are many others less-well known – the gorgeous orange-bellied and golden-shouldered parrots of Australia, many large raptors, and likely many penguins – as climate disruption takes hold.”

The study was released one day after Pope Francis issued the Vatican’s first-ever encyclical on the environment and climate change, a 184-page letter urging Catholics and “all humanity” to respect nature, rein-in development and address global warming. It also comes six months ahead of a U.N. climate summit in Paris, where President Barack Obama and other world leaders reportedly hope nearly 200 nations will agree to reduce their carbon emissions.

Francis emphasized the need for swift action, a theme echoed by the research team.

“It really is possible to fix these big problems if people put their minds to it,” Barnosky says. “We’re at a stage now where people are becoming aware of the problem, and as people become aware we can move the needle toward making progress.”

[ MORE: EPA Sets Stage to Limit Aircraft Emissions]

That includes switching from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources like wind and solar, producing food more efficiently and limiting population growth. But no matter what actions are taken, there will inevitably be a cost, experts say.

“We’re not only in the midst of a sixth major extinction, we’re moving further and further into it,” says Bruce Stein, senior director of climate adaptation and resilience at the National Wildlife Foundation. “It’s clear that we are going to lose a lot of things, but it’s also clear that we have the ability to ensure that many of our systems will be different but will continue to have ecological functionality and continue to support many of these species.”

Germany is turning 62 military bases into wildlife sanctuaries

The German government has announced plans to convert 62 disused military bases just west of the Iron Curtain into nature reserves for eagles, woodpeckers, bats, and beetles.

Environment Minister Barbara Hendricks said: “We are seizing a historic opportunity with this conversion – many areas that were once no-go zones are no longer needed for military purposes.

“We are fortunate that we can now give these places back to nature.”

Together the bases are 31,000 hectares – that’s equivalent to 40,000 football pitches. The conversion will see Germany’s total area of protected wildlife increase by a quarter.

Together the bases are 31,000 hectares – that’s equivalent to 40,000 football pitches. The conversion will see Germany’s total area of protected wildlife increase by a quarter.

After toying with the idea of selling the land off as real estate, the government opted instead to make a grand environmental gesture. It will become another addition to what is now known as the European Green Belt.

A spokesperson from The European Green Belt told The Independent: “In the remoteness of the inhuman border fortifications of the Iron Curtain nature was able to develop nearly undisturbed.

A spokesperson from The European Green Belt told The Independent: “In the remoteness of the inhuman border fortifications of the Iron Curtain nature was able to develop nearly undisturbed.

“Today the European Green Belt is an ecological network and memorial landscape running from the Barents to the Black Sea.”

One-stop lending – “Tool libraries” are popping all over Canada

In futuristic sci-fi scenarios, while we grapple with bioengineering and artificial intelligence, we should also consider the public library.

Patrons could borrow a copy of Blade Runner, a table saw, a blender and a tennis racket from what Lawrence Alvarez calls “resource hubs.”

He hopes this is where the sharing economy is headed – one-stop lending.

Alvarez is the co-founder of the Toronto Tool Library, a growing tool-sharing organization on trend with the likes of titans Uber and Airbnb. He’s an entrepreneur in the popular and lucrative sharing economy – the market where individuals rent out property to strangers and access is the new ownership.

But Alvarez isn’t in it for the money. Instead, the non-profit library lends donated tools to members for an annual $50 fee (negotiable for students and low-income neighbours), in order to help build a more sustainable community and world.

He is reversing an ironic trend started by the sharing economy – commercializing the basic human instinct to share.

The sharing economy has largely been hijacked by for-profits like Airbnb, whose founders are now billionaires. But for-profit companies miss markets that lack strong financial motivation – hyper local groups or marginalized populations – where economies of scale don’t work. It’s why Uber, the ride-sharing program, is largely available in dense urban areas. And a recent study suggests that collaborative consumers tend to be affluent millennials, since they are the target demographic.

Tool libraries are popping all over Canada. Valhalla members visited one in Montreal.

There’s nothing wrong with the for-profit sharing model, but there is also room for people with more altruistic goals to leverage the changing culture of sharing, and to avoid excluding certain groups.

When we’re young, we’re taught to share in order to build friendships. Then we grow up and accumulate stuff to gain status. Maybe we’ve reached the zenith of individual materialism and are now evolving to value reputation and reciprocity in our transactions. In the non-profit sharing economy Alvarez is advancing, we rely on our neighbours more, hearkening back to a time before we put up fences.

The same trust that allows strangers to sleep in our beds via Airbnb allows us to share things for free; it’s the spirit of the sharing economy that could use a boost beyond profit. There’s already neighbourhood.net, a non-profit forum for residents in some Canadian cities to share everything from ladders and bikes to coffee grinders and cat carriers. Swapsity, a social enterprise, hosts a bartering website where people post both skills and wish lists. One user is looking to swap German lessons or pet sitting for a microwave or organic produce.

While a culture of sharing helps build communities, it also preserves our planet. Sharing resource-intensive things like cars and power tools saves energy and may help combat a cultural obsession with ownership and acquiring things.

We would love to see the non-profit sharing model go regional for smaller and at-risk communities that are underserved by the sharing-for-profit market. In the U.K., the charity Food Cycle takes surplus food donated from grocers, cooks it up with kitchen space shared by volunteers near its local hubs, and delivers it to those at risk of food poverty.

As kids, our first social action campaign was a petition to save the Gallanough Public Library in Thornhill, Ont., which makes us especially excited about last month’s opening of a Toronto Tool Library location at Downsview Public Library – the first tool-lending program in a Canadian public library.

More libraries need to diversify, making it possible for a whole neighbourhood to share not just a dog-eared copy of Fifty Shades of Grey, but an inventory of kitchen appliances and lawn mowers in a culture that values resource preservation and community over having lots of stuff.

For now, you can borrow a novel and hammer from a single location. The future is here.

Brothers Craig and Marc Kielburger founded a platform for social change that includes the international charity Free The Children, the social enterprise Me to We and the youth empowerment movement We Day.

Chemists devise technology that could transform solar energy storage

( Nanowerk News) The materials in most of today’s residential rooftop solar panels can store energy from the sun for only a few microseconds at a time. A new technology developed by chemists at UCLA is capable of storing solar energy for up to several weeks — an advance that could change the way scientists think about designing solar cells.

The findings are published June 19 in the journal Science (“Long-lived photoinduced polaron formation in conjugated polyelectrolyte-fullerene assemblies”).

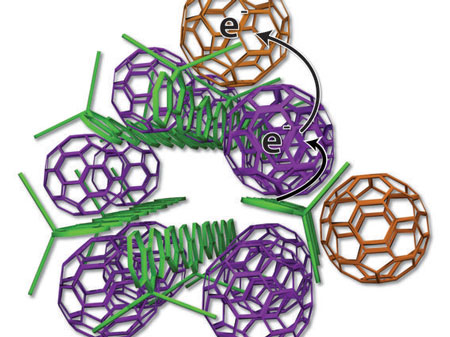

The scientists devised a new arrangement of solar cell ingredients, with bundles of polymer donors (green rods) and neatly organized fullerene acceptors (purple, tan).

The new design is inspired by the way that plants generate energy through photosynthesis.

“Biology does a very good job of creating energy from sunlight,” said Sarah Tolbert, a UCLA professor of chemistry and one of the senior authors of the research. “Plants do this through photosynthesis with extremely high efficiency.”

“In photosynthesis, plants that are exposed to sunlight use carefully organized nanoscale structures within their cells to rapidly separate charges — pulling electrons away from the positively charged molecule that is left behind, and keeping positive and negative charges separated,” Tolbert said. “That separation is the key to making the process so efficient.”

To capture energy from sunlight, conventional rooftop solar cells use silicon, a fairly expensive material. There is currently a big push to make lower-cost solar cells using plastics, rather than silicon, but today’s plastic solar cells are relatively inefficient, in large part because the separated positive and negative electric charges often recombine before they can become electrical energy.

“Modern plastic solar cells don’t have well-defined structures like plants do because we never knew how to make them before,” Tolbert said. “But this new system pulls charges apart and keeps them separated for days, or even weeks. Once you make the right structure, you can vastly improve the retention of energy.”

The two components that make the UCLA-developed system work are a polymer donor and a nano-scale fullerene acceptor. The polymer donor absorbs sunlight and passes electrons to the fullerene acceptor; the process generates electrical energy.

The plastic materials, called organic photovoltaics, are typically organized like a plate of cooked pasta — a disorganized mass of long, skinny polymer “spaghetti” with random fullerene “meatballs.” But this arrangement makes it difficult to get current out of the cell because the electrons sometimes hop back to the polymer spaghetti and are lost.

The UCLA technology arranges the elements more neatly — like small bundles of uncooked spaghetti with precisely placed meatballs. Some fullerene meatballs are designed to sit inside the spaghetti bundles, but others are forced to stay on the outside. The fullerenes inside the structure take electrons from the polymers and toss them to the outside fullerene, which can effectively keep the electrons away from the polymer for weeks.

“When the charges never come back together, the system works far better,” said Benjamin Schwartz, a UCLA professor of chemistry and another senior co-author. “This is the first time this has been shown using modern synthetic organic photovoltaic materials.”

In the new system, the materials self-assemble just by being placed in close proximity.

“We worked really hard to design something so we don’t have to work very hard,” Tolbert said.

The new design is also more environmentally friendly than current technology, because the materials can assemble in water instead of more toxic organic solutions that are widely used today.

“Once you make the materials, you can dump them into water and they assemble into the appropriate structure because of the way the materials are designed,” Schwartz said. “So there’s no additional work.”

The researchers are already working on how to incorporate the technology into actual solar cells.

Yves Rubin, a UCLA professor of chemistry and another senior co-author of the study, led the team that created the uniquely designed molecules. “We don’t have these materials in a real device yet; this is all in solution,” he said. “When we can put them together and make a closed circuit, then we will really be somewhere.”

For now, though, the UCLA research has proven that inexpensive photovoltaic materials can be organized in a way that greatly improves their ability to retain energy from sunlight.

First retailer in Canada to go completely off the grid

“We didn’t want just a store. We wanted something that fully encompasses what we were doing.”

So says Paul Long, the co-owner of Anian, a surfboard company making waves from inside their own, solar-powered headquarters.

When they originally purchased a downtown Victoria lot for their business in 2013, they were planning to power it conventionally.

“I really thought I was going to pull power from the city,” says Nick Van Buren, the other co-owner.

“[But] it’s about $5500 to get a pole on this side, and then you’ve got to have a power bill.”

It forced them to think outside the box for their power needs. Their buildings are made solely from recycled and reclaimed materials, and they recently had a successful crowdfunding campaign to purchase four 250-watt panels.

It’s enough to power all the necessary lights and tools, with plenty left if the company ever expands.

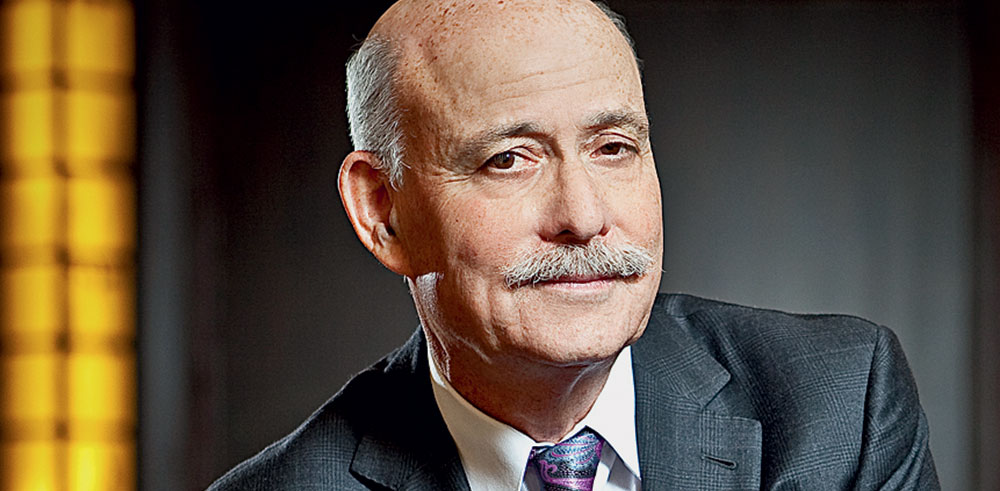

The Architect of Germany’s Third Industrial Revolution: an Interview with Jeremy Rifkin

![]() On May 11 of this year, 74% of Germany’s electricity was produced from a combination of solar and wind power, driving electricity prices into the negative for much of the afternoon.

On May 11 of this year, 74% of Germany’s electricity was produced from a combination of solar and wind power, driving electricity prices into the negative for much of the afternoon.

Meanwhile, in the United States, fossil fuels accounted for 67% of this country’s electricity. In the US, the chief arguments against renewable energy include: a) green energy is bad for the economy; b) green energy kills jobs; and c) green energy is expensive compared with fossil fuels.

Despite its apparent green energy handicap, Germany’s economy is still standing. With a quarter of the US population, Germany’s economy is the world’s fourth largest in terms of GDP.

The architect of Germany’s energy revolution, economist Jeremy Rifkin, argues that green energy critics have it backwards when it comes to the impact of renewable energy on economic growth. Far from annihilating the German economy, Mr. Rifkin argues that renewable energy is an essential component of a third industrial revolution that will potentially triple productivity, while slashing marginal costs. According to Mr. Rifkin, the resulting “Internet of Things” and “Collaborative Commons” that emerges from the German third industrial revolution will propel Germany’s economy well beyond countries like the United States that rely on sunset fossil fuel energies and reject investment in modern communications, energy and logistics infrastructure.

Jeremy Rifkin is the bestselling author of twenty books on the impact of scientific and technological changes on the economy, the workforce, society, and the environment. His books include the New York Times bestseller The Third Industrial Revolution, and his latest, The Zero Marginal Cost Society: The Internet of Things, the Collaborative Commons, and the Eclipse of Capitalism.

Mr. Rifkin is the principle architect of the European Union’s Third Industrial Revolution long-term economic sustainability plan to address the triple challenge of the global economic crisis, energy security, and climate change. The Third Industrial Revolution was formally endorsed by the European Parliament in 2007 and is now being implemented by various agencies within the European Commission as well as in the 27 member-states.

Mr. Rifkin has served as an adviser to Chancellor Angela Merkel of Germany, President Nicolas Sarkozy of France, Prime Minister Jose Socrates of Portugal, Prime Minister Jose Luis Rodriguez Zapatero of Spain, and Prime Minister Janez Janša of Slovenia, during their respective European Council Presidencies, on issues related to the economy, climate change, and energy security. He currently advises the European Commission, the European Parliament, and several EU and Asian heads of state.

So, my question for you is, why hasn’t Germany’s economy crashed? One of the principal arguments against renewable energy is that it kills jobs and has catastrophic effects on the economy. But Germany still seems to be standing – why is that?

Well, let me go back and give a little bit of history to this. When Chancellor Merkel became chancellor, she asked me to come to Berlin to address the question, “How do we grow the German economy and create new business opportunities and jobs?” And when I got to Berlin, the first question I asked the new chancellor was, “How do you grow the Germany economy, or the EU economy, or the global economy in the last stages of a great energy era?”

If you look at every economic paradigm in history, they all have a similar signature: when an economic paradigm shift occurs, three technology revolutions emerge, and converge to create a general purpose technology platform. New forms of communication to manage economic activity. New forms of energy to power economic activity. New forms of transport and logistics to move economic activity.

When they come together in a general purpose technology platform or infrastructure that’s seamless, it changes temporal-spatial relationships. It allows economic activity to play over a larger field in time-space, and to create a more integrated economic society.

For example in the 19th century, printing and the telegraph emerged as a communication media, and it congealed with cheap coal and the steam engine for energy and power, and the locomotive and national rail systems, which allowed us to go from local to national markets. It was a change to our economic core, and it allowed us to create vertically integrated shareholding companies to create economies to scale, put out mass consumer products, hire a lot of people, and move the economic agenda.

In the 20th century, the telephone, and, later, radio and television became a communication media to manage and market a cheap oil-powered society. And the new transport and logistics system was the internal combustion engine and national road systems.

So, the first industrial revolution gave us an urban economic environment. The second industrial revolution gave us an urban-to-suburban dispersed economic environment, and it led to the beginning of modern globalization.

Now, let me explain what this means in terms of the first question you raised about Germany. There’s a big misunderstanding among my colleagues about the nature of productivity. There is a dirty little secret in economics, which the economists don’t want to talk about because it goes right to the hub of their unsuccessful economic theories, which is, “What is the nature of productivity growth?”

All classic/neoclassic economic theory has said there are two factors that create productivity growth: better machines, better workers. But when Robert Solow won the Nobel Prize for economic growth theory back in the ’80s, he let the secret out. He said, “We’ve got a problem.” When we track every single year of the industrial revolution, these two factors account for about 14 percent of productivity and growth. So, where does the other 86 percent come from? They don’t know. It’s called the Solow residual.

And a guy named Moses Abramovitz, former head of the American Economic Association, said, “This is a measure of our ignorance.”

Now, most people say, “How can economists not know? How can they actually not know what’s the nature of productivity growth? That’s the whole basis of economics.”

When economic theory was developed in the 1700s, the big rage was still in physics. So, all the economics philosophers used Newton’s metaphors to make their new discipline seem scientific, so, Newton’s Law, that for every action there’s an equal and opposite reaction. So, Adam Smith borrowed that metaphor for his supply and demand curve.

The only problem with basing an entire economic theory on Newton’s physics is Newton’s physics don’t have anything to do with economics. Nothing. It’s the law of gravity. Economics are based on the laws of energy – the first and second laws of thermodynamics.

The first law of thermodynamics: you cannot create or destroy energy. All the energy in the universe has been there since the beginning. That’s the conservation law.

The second law is energy does change form, but only from hot to cold, from available to unavailable, from order to disorder. So, if you take a piece of coal, it has bounded energy. When you burn it, and it moves into gases, none of the energy’s lost. But now it’s not a hunk of coal. It’s dispersed gases. It can do useful work for you. You can recycle it, but then you have to use energy to recycle it. There’s always an energy loss; that’s called “entropy,” – the amount of energy lost in using energy.

So this is what economics is about. We take low entropy available energy in nature. It can be a metallic ore, a rare earth, natural gas, whatever it is. But everything is bound energy, not just oil. Everything. Every material is.

So, we take those natural resources out of nature, which has bounded energy, and every step of moving it across the value chain – the conversion, the logistics, the distribution, the warehousing – every time we convert that to the next stage in the value chain, there’s energy that’s embedded into the product versus the actual energy wasted that never goes into it just because we have low efficiencies.

So, the 20th century second industrial revolution started at three percent aggregate energy efficiency in 1905. Now, with the amount of energy in each step of conversion that actually went into the product, 97 percent was wasted just in using it.

We got up to 14 percent aggregate energy efficiency in the 1980s, 14 percent embedded in each stage of the value system, but everything that we used from nature in a society back to nature – 14 percent embedded, 86 percent wasted, lost entropy.

So, per Adam Smith, we believe that we’re adding value during every step along the value chain, when the reality is that we’re actually adding cost?

That’s correct.

Gross domestic product is not a measure of your wealth, it’s really a measure of your debt.

You see, John Locke said, “Everything in nature is waste in the commons. And then when we harness it, we create value and property.” In other words, we take nature’s waste and turn it into valuable wealth.

It’s the exact opposite. From a thermodynamic point of view, everything in nature is valuable energy, and whatever we convert, it can be a rare earth metal, we convert it, and every step we’re losing energy, and then eventually, whatever we actually use, whether it be a good or a service, eventually goes back to nature more degraded. We then can recycle it so we don’t lose it all, but it’s a measure of our debt, not a measure of our wealth.

So, it’s a zero-sum game – GDP is our debt to the Earth?

That’s correct.

There’s a paradox deeply embedded in the heart of capitalist theory and practice that we just never saw before. And the paradox has led to the great success of the invisible hand of the marketplace. Now the irony is that paradox is actually becoming so successful that it is actually creating a new economic system flourishing alongside the capitalist market, which we call the “Collaborative Commons.”

You and I, and everyone else, have already been up on the collaborative commons, where we’ve created the videos on YouTube, a news blog or whatever, and we are bypassing the traditional market exchange economy, and we’re in a shareable economy, not an exchange economy. Capitalism creates an exchange economy. Collaborative commons creates a shareable economy.

Hundreds of millions of people already participate in the sharable economy. So, they’re not only sharing entertainment and video news and ebooks and now massive open online courses, they’re now sharing renewable energy. And there’s zero marginal cost on a collaborative commons.

But the expectation was that the zero marginal cost phenomena would not pass across the firewall from the virtual world of bits to the physical world of atoms. Now that firewall’s been breached, and the agent is this Internet of things.

So now, the communication Internet is beginning to emerge and converge within this nascent energy Internet of renewables and a fledgling transport and logistics Internet to create this Internet of things.

There are now hundreds of thousands of hobbyists producing and sharing their own 3-D printed products made out of materials from recycled materials, with open-source software for the instructions on how to make their products.

We never expected, in our wildest imagination, a technology revolution so extreme in its productivity that it can reduce marginal costs to near zero, potentially making some goods and services actually free and abundant beyond market forces.

That’s what’s going on. That’s the big ticket change happening. And what we’re beginning to see in Germany.

Here’s the bottom line – my global team has run an economic study on how much more aggregate energy efficiency and productivity we could get. Our results show that we can go from about 14 percent aggregate energy efficiency, which is the height of the second industrial revolution in the U.S. in 1980s and 1990s, to 40 percent and maybe even 60 percent aggregate energy efficiency in the third industrial revolution. That’s huge.

How does the US fare relative to countries like Germany in the global economy?

Germany’s the most robust industrial economy per capita in the world.

And the U.S. is nowhere. The energy companies have huge sway. They’ve convinced America that we’re energy independent, and that climate change is a hoax. And so, we’re staying in these old 20th century fuels, whose prices are volatile and going up and down wildly on world markets, because we’re in the sunset for the fossil fuel. It’s not sunrise energy; it’s a sunset energy.

Tar sands in Canada are not competitive under $70.00 a barrel. The only reason they’re on the market is because the price of oil keeps going up. Shale gas is a bubble.

What happened to the U.S. is that companies invested wildly in buying up every shale gas deposit at the same time. And they’re milking the sweet spot. Every shale gas deposit has a little sweet spot, you milk it in 18 months, and then there’s nothing there. So, the price of natural gas has gone down dramatically, because they’re all milking the sweet spots of all the deposits they invested in at the same time. Even our Department of Energy in the U.S. and the International Energy Agency have said that, by 2020, those prices are going to go back up again.

What’s happened with solar and wind is it’s been on an exponential curve for 20 years. That’s what a lot of folks in America don’t realize, and Europeans do. A solar watt in 1970 cost something like $66.00. This afternoon, a solar watt is $.66 to produce, and it’s going down, down, down. So it’s on a 20-year exponential curve.

Why can’t America build an Internet of Things?

Remember when Obama said, “You didn’t build that” during the campaign?

Everyone went berserk on the right?

Yes.

What he was saying is, the infrastructure is built by the American people through their tax dollars. If you have the infrastructure, that’s how any business – small, medium, large – plugs into the technology infrastructure. And that’s how you’ll then create your own opportunities. You have to have the telephone lines, and the roads, and the school systems, and the electricity grids, and the pipelines. All of that are underwritten, subsidized, or in some way involved with government laying out infrastructure.

Half the country doesn’t understand that. So, if you eliminate government engagement laying down infrastructure, you’re baked. And what’s happening here is nobody wanted to invest in the third industrial revolution infrastructure.

Nobody wants to invest in the Internet of Things platform. How will we ever be able to move into the next economic era in history and dramatically increase productivity, create a sustainable model?

It almost seems as though we might have to wait until our market collapses and the third industrial revolution rises out of the rubble.

Well, I just don’t know. My hope is the millennial generation will see the opportunities here, because this is really a young person’s revolution. Kids that grew up on the Internet, and they’re now 20, 30, 40, they were empowered in lateral economies of scale. My generation, we thought that – we would say lateral power is an oxymoron. It’s always pyramidal.

But for everyone that grew up on the communication Internet, it is actual lateral power – that their individual entrepreneurial abilities depend on how much they can benefit everyone else in the laterally scaled network.

So, they don’t buy Adam Smith. They read Adam Smith, and they think, “This makes no sense.”

Adam Smith says, “Each person pursues their own self-interest, and by doing so, it optimizes the common good” – which has always been a little dubious. Young people believe by each person benefiting the network, creating social capital by creating things that benefit the network, it increases their social reputation and their social capital allows their social entrepreneurial skills to succeed.

So, what I like about this third industrial revolution is that it borrows the best. This collaborative commons that’s emerging out of capitalism borrows the best from capitalism, the best from socialism. It takes out the bad parts, which means it eliminates the centralization of the market with vertically integrated monopolies, and it eliminates the centralization of command and control from centralized governments in the socialist systems.

But what it does keep is the entrepreneurial spirit of capitalism in each individual. It also keeps the social commitment that we see in socialism that no one’s left behind. So, that’s why our younger generation are social entrepreneurs, and they see themselves as benefiting the world.

Ecoshelta prefab homes strive for sustainability from the ground up

Australian Architect Stephen Sainsbury has spent decades researching materials to reduce environmental impact. This has culminated in the development of the Ecoshelta prefabricated modular building system.

Based on an extensive evaluation of the environmental impact of building materials and other factors, the Ecoshelta Pods are constructed using a combination of eco-friendly timber, a composite panel roof, the latest wall and floor technologies and marine grade structural aluminum alloy.

Some may consider the choice of aluminum slightly controversial as it’s not the first material that springs to mind when considering a green alternative. However, Sainsbury’s 20 year study found aluminum to be a highly durable, long-term product that can be recycled repeatedly with minimal impact. It is also five times as strong as steel and half the weight, with only a quarter of the material needed.

The buildings were originally designed for installation in remote areas, with the ability to withstand extreme temperatures and conditions. The use of aluminum means that fire and cyclone rated buildings can be made directly from the material, without having to add any other resources to it.

But it’s not just the raw materials that have undergone intense scrutiny. Every step in the design process has been through a calculated evaluation of the potential environmental impact. This includes a thorough examination of the mining and manufacturing processes, transport and logistics, with consideration given to where the product is made, how far it has to travel and whether it will pollute the internal or external environment.

The Ecoshelta Pods can also be transported and delivered to any location, near and far. A recent commission saw Sainsbury and his team on a million acre station in the Kimberley, installing an accommodation building in 130 degree heat, hundreds of miles from the main gate. Another Pod was packed and shipped to Hong Kong for installation as a garden pavilion.

The Pods are usually assembled by a team from Ecoshelta or overseen by an Ecoshelta supervisor but for those with a keen sense of determination, the assembly can be managed as a DIY project. Each structure takes between one and five days to construct and needs at least four people to assemble.

A feature that makes the prospect of DIY more attractive is the innovative one-screw connection system. The average structure contains around 3000 screws, all alike, used to assemble the entire building. Think of it as a sophisticated Ikea package, with a power-driven screw in place of the Allen key. Although as with Ikea assembly, skills in the trades would be advantageous.

As part of the overall design, careful consideration has been given to light and airflow, natural ventilation, passive and active solar design which can be used for heating, cooling, fans, lights and powering a building.

The outcome is an aesthetically pleasing and versatile building that can be customized to your own taste. It’s almost like buying a car, selecting from half a dozen basic designs and then tailoring it to meet your needs. Everything can be custom selected from the various roof forms, different cuttings, linings, windows, doors, even down to the bathroom and kitchen details.

A basic model can cost around US$25,000 (AU$35,000), but most buyers spend anywhere from $38,500 to $54,000 per Pod. For those wanting a larger home, a 1600 square foot house would be in the region of $270,000.

For Sainsbury, the research continues. He is committed to the business of sustainability and exploring cutting edge technologies to minimize environmental impact. For the environmentally aware, an Ecoshelta Pod would be the ideal way to go green in style.

Source: Ecoshelta

Born in Melbourne, Australia, and raised on a diet of world travel and cultural delights, Jana has always suffered from the affliction of More is More. Not content with her ten years working as a therapist, she also fronts a Blues band, completed a Masters and writes features for a living. She has a keen interest in travel, health and wellbeing and, most regrettably, her PVR. All articles by Jana Firestone

Post a Comment Related Articles

The man who grows fields full of tables and chairs

At first glance it is a typical countryside scene. Deep in the Derbyshire Dales, young willow trees stretch upwards towards the late spring sun. Birds, bees and the odd wasp provide a gentle soundtrack to the bucolic harmony.

But laid out in neat rows in the middle of a field are what appears to be a rather peculiar crop.

On closer inspection these are actually upside-down chairs, fully rooted in the sandy soil.

Slender willows sprout out of the ground then after a few inches the trunk becomes the back of a chair, the seat follows and finally the legs. The structure is tied to a blue frame and the entire form is clothed in leaves.

Surveying the landscape in front of him is Gavin Munro, co-founder of Full Grown, the company he formed to put a childhood vision into practice.

“The concept is pretty straightforward. Rather than cutting down trees and making furniture I wanted to grow the trees in the shape of chairs, mirrors, lamps and so on.”

On the next row along, elegant spirals are growing around cylinders. These will eventually be used as hanging lamps. There are also mirror frames, tables and hammocks.

Patience required

The way Gavin describes the process makes it seem remarkably simple.

“We grow the trees, shaping them as they go along, it’s a little bit like espalier – the process of training trees,” Gavin explains.

“When they’ve formed the specific shape we want, they’re cut down and dried out, giving you a finished chair that has grown into one solid piece.”

It’s a long process, taking around six years from start to finish. But Gavin is a patient man.

“As a child I had a spinal condition and underwent surgery to straighten my back. Part of the treatment was in effect being grafted on a frame, similar to the way we graft trees. So I appreciated how forms can be shaped – and how long the process can take.

“Around about the same time, my mum had a bonsai tree. The bonsai was left to grow in its own direction and eventually formed itself into the shape of a throne. I was intrigued by this, the thought of a chair being created directly from nature.”

Shopping at the beach

Gavin’s fascination with trees and wood grew into a business when he moved to California. He made his main living working as a gardener, but started to craft furniture from driftwood as a sideline.

“You do your shopping at the beach, collecting materials from what’s washed up. You’re using what’s already there and there’s a certain satisfaction to that.”

When Gavin returned to England, he wanted to continue working with the natural environment. Thinking back to his mum’s bonsai, an idea begun to form,

“If a bonsai grew into a chair shape, why not other furniture? Why couldn’t I grow a whole field of it? There’d be no waste plus it’d be structurally stronger.”

Ten years ago Gavin put his plan into action. With a £5,000 investment from a supportive friend he bought the basics, including a lawnmower, moulds and other equipment. There was some experimentation with materials to begin with.

“We looked at different types of wood and eventually settled on willow as the main crop. It’s fast growing and relatively easy to work with.

“We wanted to offer other varieties such as cherry and oak, both for customer choice and also to spread the risk if they fall prey to a disease. I love the look of ash, for example, but it easily gets [the fungal disease] ash dieback.”

Pest control

There’s also the problem of pests, says Gavin, who’s trying to create a solution from the natural environment.

“I guess you could call this an open air factory and we’re using this to our advantage. We’ve taken on permaculture ideas, for example, tempting birds on to the land with nuts so that they’ll eat the aphids and caterpillars.

“We’ve also planted clover under the trees. The roots fix the nitrogen so the trees can access it better and the clover also covers the soil so it’s not damaged by the sun.”

In a world where you can pick up the entire furnishings of your house in one afternoon in Ikea, Gavin’s slower alternative seems to have caught the imagination of buyers.

“Our first crop of chairs should be ready to harvest next year and we’ve already sold out of pre-orders. We’ve also had a lot of interest from people around the world who are interested in doing something similar.”

The pre-orders for chairs and lamps are sustaining the business for the time being and have generated just enough money to pay a few staff, one full-time and several part-time including Gavin’s wife Alice.

The time, effort and skills required to grow furniture mean that the pieces don’t come cheap, however. Chairs are priced at £2,500, lamps start at £700 and mirror frames £450.

So is grown furniture just something for the well-heeled and deep-pocketed? This is the case for the time being, but Gavin says his plans could see that change.

“We have a 50-year plan. There’s plenty of scope for global scaling. Wherever trees grow, you can grow furniture,” he reasons.

Biomimicry inspires the development of environmentally sustainable performance apparel

Designers of performance apparel are being urged to look to nature for inspiration when developing their ranges, according to a new report from the global business information company Textiles Intelligence – Biomimicry: science of nature inspires design of high-tech performance apparel.

This process, known as biomimicry, is being driven in part by the need to make performance apparel items more environmentally sustainable and, in particular, recyclable at the end of their useful lives. This is not easy at present as performance apparel is becoming increasingly sophisticated and is being manufactured from a variety of polymeric fibres and other materials.

Advocates of biomimicry point to the fact that animals, insects, plants and other living organisms have survived and adapted in dynamic environments by evolving over billions of years, and many natural adaptations have proved to be more effective than man-made solutions.

The wing of the morpho butterfly, for example, has inspired developers to produce fabrics in vivid colours without the use of pigments or dyes. In Japan, Teijin Fibers has developed a chromogenic fibre called Morphotex by arranging polyester and nylon fibres in 61 alternating layers.

Many plants and insects have surfaces with water repellent properties which have provided inspiration for the development of water repellent and stain repellent materials for use in hunting outfits, military uniforms, rainwear and skiwear.

Schoeller Technologies in Switzerland has copied the self-cleaning properties of the lotus leaf in its development of NanoSphere – a finishing process which is said to be one of the most functional and sustainable water repellent treatments on the market, as well as being one of the safest. It has also developed ecorepel – a water repellent finish made from long chain paraffins which are biodegradable.

Schoeller Technologies has also looked to pine cones for inspiration in the development of a product called c_change – a windproof and waterproof hydrophilic membrane with a flexible polymer structure which reacts independently to changing temperatures. At high temperatures, when body moisture levels rise, the structure of the membrane opens to allow excess heat and moisture to escape. At cooler temperatures the structure contracts, thereby helping the body to retain heat and prevent chilling.

Researchers in the textile industry have also taken inspiration from the ability of birds and polar bears to remain warm in cold or even freezing temperatures in the design of thermal insulation garments.

One team of scientists has even created a self-repairing water repellent fabric for use in the manufacture of garments which are designed to be worn by fishermen and sailors. The fabric’s surface features microcapsules containing a glue-like substance. When the fabric is damaged, the microcapsules rupture and the substance is released and subsequently hardens, thereby repairing the damage.

Other properties inspired by nature include antimicrobial efficacy, bioluminescence, camouflage, drag reduction, dry adhesion – inspired by the toe pads of the gecko – and high strength.

Specialists in solutions inspired by nature for the performance apparel industry are continuing to make valuable new discoveries. This is thanks in no small measure to advances in technology – especially nanotechnology – which have enabled such specialists to probe more deeply into biological mechanisms.

These discoveries will no doubt pave the way for the introduction of new types of fabrics and garments which are smart and sustainable.

Biomimicry: science of nature inspires design of high-tech performance apparel was published by the global business information company Textiles Intelligence and can be purchased by following the link below:

Biomimicry: science of nature inspires design of high-tech performance apparel

Other recently published reports from Textiles Intelligence include:

Performance apparel markets – product developments and innovations, (4Q, 2014) Profile of Vaude: a role model for sustainability Performance apparel markets – business update, (4Q, 2014)