- From the section Science & Environment

Neuroscientists have found that they can identify individuals based on a coarse map of which brain regions “pair up” in scans of brain activity.

The map is stable enough that the researchers could pick one person’s pattern from a set of 126, by matching it to a scan taken on another day.

This was possible even if the person was “at rest” during one scan, and busy doing a task in the other.

Furthermore, aspects of the map can predict certain cognitive abilities.

Presented in the journal Nature Neuroscience, the findings demonstrate a surprising stability in this “functional fingerprint” of the brain.

“The exciting thing… is not that we can identify people by putting them in an MRI machine – because we can identify people just by looking at them,” said Emily Finn, a PhD student at Yale University who co-wrote the study with her colleague Dr Xilin Shen.

“What was most exciting to me was that these profiles are so stable and reliable, in the same person, no matter if it’s today or tomorrow and no matter what your brain is doing when we’re scanning you.”

Predicting intelligence

Crucially, this fingerprint is based on brain activity – not the organ’s physical structure.

In the the myriad links between our billions of brain cells, and even at the level of a normal MRI scan, we are all physically unique.

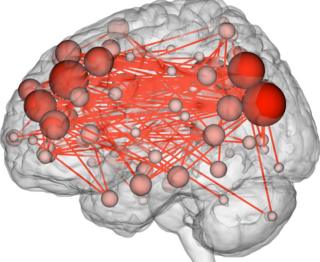

But Ms Finn and her colleagues drew a map of each brain purely on the basis of which regions, in each individual, tended to leap into action at the same time. They used data from functional MRI (fMRI), which records subtle ups and downs in the busyness of the brain.

Because it is relatively imprecise, fMRI has not typically been used to compare individual brains. Instead, scientists tend to record from several subjects and average the results.

“We were interested in flipping the traditional fMRI analysis on its head, and not asking what are the commonalities – how do all brains look the same, doing the same task – but rather, does the same brain look the same, regardless of what it’s doing?” Ms Finn explained.

So they took fMRI results from the first 126 subjects of the Human Connectome Project, a huge US initiative to gather data about the brain’s “wiring diagram”. These subjects had all been scanned multiple times, on different days, both while they were resting and while they were occupied by various tests.

Within each of those scans, the researchers looked at what was happening in 268 key spots within the brain: how closely did the ups and downs at this spot match the ups and downs at all 267 other spots?

This produced a profile of the flow of activity in each brain. And that profile was consistent enough that the team could use it to pick out the same individual – more than 90% of the time – from a different set of scans, done on a different day.

They also found that they could use the profile to predict, to a certain degree, how well the subjects did at particular cognitive tests that measured “fluid intelligence”.

This is a type of on-the-spot, untrained reasoning that is measured by some IQ tests. Ms Finn is quick to point out that her technique could never substitute for those questionnaires.

“None of us would recommend a brain scan over an IQ test,” she said. “This is just proof-of-concept that these connectivity profiles are relevant to this very sophisticated cognitive behaviour.”

If these individual maps show strong associations with psychological phenomena, she added, they could prove useful in the clinic.

“This opens the door to predicting things that are harder to tell just by looking at someone, or giving them a test – like risk for different mental illnesses.”

Ones and zeros

Recently, a different study used a very similar technique to show that these brain maps can predict a range of characteristics, from someone’s vocabulary to their income.

One of its authors, Prof Thomas Nichols, said he was not surprised that Ms Finn and her colleagues were able to distinguish individuals.

“What this is getting at is the very high-quality nature of this data,” said Prof Nicholls, a brain imaging statistician at the University of Warwick. He said the data emerging from the Human Connectome Project, which also formed the basis of his study, is “bleeding-edge, state-of-the-art” stuff.

“It’s really, really good and there’s a huge volume of data on each subject.”

Tim Behrens, professor of computational neuroscience at Oxford University, said he was most impressed by the consistency between the resting and task-based maps in the study.

“What is particularly interesting is that the way the brain connects… at rest, is so similar to how it connects during a task – when it’s doing something interesting. That’s what’s exciting about it,” Prof Behrens told the BBC.

By comparison, he said, you would not expect “the pattern of ones and noughts” in a busy computer to reflect the pattern in a computer that is not doing anything.

“It tells you that something about the function of the brain is fundamentally built into patterns of activity that just live there, all the time.”

Follow Jonathan on Twitter