Newly-Developed Concrete Absorbs CO2, Insulates & Grows Food

Researchers in Barcelona, Spain have found an innovative solution to the long-established emissions problem.

In Barcelona, Spain, researchers at Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya (UPC) have found an innovative solution to the long-established emissions problem. Science Daily reports that they discovered how to build megastructures with a biological concrete that not only lowers CO2 and regulates heat, but is pleasing to look at.

It is not only a medium for growth and a construction material, but a means to regulate temperatures indoors while removing CO2 from the atmosphere. The surface of the concrete grows mosses, lichens, fungi and other biological organisms.

The invention needs to be used in regions with a calm Mediterranean climate, but enables buildings to absorb CO2 and release oxygen with micro-algae and other “pigmented microorganisms” that coat it.

While vertical gardens certainly enhance its aesthetic appeal, one might declare that its beauty is sourced in its clever design.

The concrete works in layers: The top layer absorbs and stores rainwater and grows the microorganism underneath; it can also absorb solar radiation, which insulates the building and regulates temperatures for those who live inside. The final layer of the concrete repels water to keep the internal structure safe, shares Inhabitat.

Normal concrete has high pH levels that don’t allow plants to grow, but this newly developed one is more acidic, which lowers the pH to levels safer for growth.

The research team, led by Antonio Aguado and supported by Ignacio Segura and Sandra Manso, has big plans for the design. They share on UPC’s website:

“A further aim is that the appearance of the façades constructed with the new material should evolve over time, showing changes of colour according to the time of year.”

What are your thoughts? Comment below and share this news!

This article was written By

Do you like to read about science, technology, psychology, personal development or health? There is a new social network called Aweditoria that is purely based on interests. You can follow topics there and see the best small stories, ideas and concepts in those fields. Click here to try it out, it’s free and only takes few seconds to join. You can also follow Myscienceacademy.org on Aweditoria!

Get more content like this in your inbox!Sign up fo our free newsletter:

DYI Pallet Furniture Ideas – Easy, inexpensive & Eco Friendly

Wooden Palettes are sitting around everywhere around Montreal, waiting to be transformed. Originally they are used by businesses for big bulk shipments, but end up very often being abandoned or hanging around for months with no use or purpose at all.

This doesn’t have to be the case though, the pallets are made of good quality wood and can be reclaimed and recycled in to unique and useful projects. Pallets can be found everywhere at supermarkets, behind stores, in alleys, abandoned lots. Pretty much anywhere where there is large shipment transactions going on.

My advice to you based on my personal experience, if you want to create something with the pallets, just do it! Don’t be shy to ask the business managers or owners if you can take a few, and don’t be lazy either and make excuses that you have no way to get them. Organize for someone to help you pick the pallets up and help you deliver it to your place. If you don’t have any family or friends who are available at the time to help you, then do as I did and just put up a post on craigslist or Kijiji, in the gigs /labor section. Hire a man with a Van, it might cost a few extra bucks to help you move them but you will have something of value that you created, while at the same time being environmentally conscious and responsible.

Once you have them in your humble abode, all you need is a saw, hammer and nails, and of course your imagination! If your not too good with tools, there are many things you can create with the pallets without tools or having to take them a part.

Check out some of these interesting design ideas below. I’ve included some very simple but charming pallet furniture projects that anyone can do and some other more challenging ones for the more handy builders out there. I hope you create some beautiful creations. And don’t be afraid to push your limits, just because your not handy now, doesn’t mean that you can’t be tomorrow. Take out the drill, and use it! Don’t limit yourself by your gender either, be all that you dream of being.

We are always working on different unique Upcycling projects at Valhalla Montreal. If you would like to join in and help out with one, we are at the land every Saturday, and welcome anyone who has a calling to join in.

Wooden Pallet Coffee Table

Wooden Pallet Deck

Garden Path Made with Pallets

Wooden Pallet Bed with Storage Drawers

Wood Pallet Book/Magazine Shelf

Wooden Pallet Stair Case

Wooden Pallet Dog Bed

Wooden Pallet Outdoor Furniture

Romantic /Wedding Pallet Furniture

Kitchen Pallet Ideas

Can Google Drive the Production of Environmentally Sustainable Buildings?

Google, in partnership with thinkstep, building architecture and engineering efficiency firm Flux and the Healthy Building Network have launched a free database that aims to promote environmentally sustainable buildings.

The Quartz database is the result of a year-long collaboration known as the Quartz Project, whose overall mission is to promote the transparency of building product information. Now freely available to building owners, architects and sustainability specialists, as well as to the general public, the database brings together data on the impacts building materials have on both human health and environmental sustainability.

The partners say the Quartz database will serve as a catalyst for more sustainable materials by providing baseline information for the AEC industry. The database aggregates and standardizes the industry’s current data into an open database of valuable and actionable information that is well organized and easy to understand. It’s an open, vendor-agnostic mechanism that allows the AEC industry to compare, contrast and evaluate materials based on their impact on the environment and human health.

Quartz integrates both LCA and health-hazard data into a single information source using widely accepted and consistent methodologies, such as Pharos Project/GreenScreen hazard screening, TRACI 2.1, and ISO14044.

Data is vendor-neutral and covers 100 building products across a range of categories, such as concrete, drywall and insulation. Products are compared by composition, health impacts, and environmental impacts.

Data is licensed under Creative Commons BY 4.0, meaning there is no restriction on the use, redistribution or modification of the data.

In 2013, Google, the Healthy Building Network and more than 20 other corporations and institutions launched the Building Health Initiative, which aims to elevate green building as a public health benefit and accelerate the development of transparency standards in building materials.

Stay Up-to-Date On Environmental Management, Energy & Sustainability News with EL’s Free Daily Newsletter

New York’s JFK airport has an urban farm. Wait, what?

The potatoes in your bag of complimentary airline chips could someday come from a farm at – surprise! – New York’s John F. Kennedy International Airport.

Outside JetBlue Airways’ Terminal 5, a few thousand black plastic crates form raised beds for an urban garden. USA Today reports:

Designed to promote New York agriculture and add a bit more green space to the airport, the 24,000-square-foot T5 farm is growing produce, herbs, and the same blue potatoes used to make the Terra Blues potato chips JetBlue offers year-round as complimentary snacks to passengers during flights.

“In today’s world of genetically modified and franken-foods, it is very important to know where your food comes from,” said Brian Holtman, JetBlue’s manager of concession programs, at a farm “reveal” on Thursday. “By creating a farm at T5, we can show crew members and customers exactly where their food is coming from.”

This fledging farm-to-airplane-tray movement has a long way to go. It takes between one and three potatoes to produce each bag of JetBlue chips, according to CBS, and JetBlue hands out 5.8 million bags each year. The potatoes grown in the airport’s garden (smaller than half a football field) would meet less than 1 percent of that demand, CBS points out. That’s not the plan for right now anyway: The farm will provide produce for the terminal’s restaurants.

Starting an urban garden at an airport wasn’t easy. Since encounters between wildlife and airplanes are costly, the plants were specially selected to attract bees and butterflies – and not heftier fauna. In addition, the garden’s plastic crates were bolted to the ground to ensure the garden could withstand the force of an earthquake or Katrina-level-hurricane.

So the question remains: Why? The company hopes that this unlikely farming experiment will improve air quality around the terminal and educate the garden’s visitors in addition to providing airport food.

However, when compared to the huge carbon footprint of air travel (which accounts for 2.5 percent of global emissions), the garden is small potatoes.

Hamburg Sets Out to Become a Car-Free City in 20 Years

By Ignasi Jorro in Barcelona

Hamburg City Council has disclosed ambitious plans to divert most cars away from its main thoroughfares in twenty years. In order to do so, local authorities are to connect pedestrian and cycle lanes in what is expected to become a large green network. In all, the Grünes Netz (Green Web) plan envisages “eliminating the need for automoviles” within two decades.

By connecting the entire urban centre with its outskirts Hamburg is expecting to smooth inner traffic flow. In all, the northernmost city is to lay out new green areas and connect them with the existing parks, community gardens and cementeries.

Upon completion of the plan Hamburg will pride itself on having over 17,000 acres of green spaces, making up 40% of the city’s area.

According to an official, the ambitious plan will “reduce the need to take the car for weekend outings outside the city”.

Although vehicles are not to be banned from the main thoroughfares, the council expects residents and tourists alike to be able “to explore the city exclusively on bike and foot.”

At the same time, the green ring will play a crutial role to help the metropolis fight against rising temperatures and urban flooding.

The average temperature in Germany’s second-largest city has risen by 9 degrees Celsius in scarcely half a century, experts warn.

As regards to leisure, the interspersed patches of green areas will let residents “hike, swim, do water sports, enjoy picnics and restaurants, experience calm and watch nature and wildlife right in the city”.

28 DIY Uses for Old Wood Palettes

Companies often throw out old wooden palettes and other similar materials. If you take the time to find a good source for them, you can build all kinds of amazing things yourself. Not only can you build rugged outdoor furniture that will last a lifetime, you can give it some extra finishing and make some …

Can A Grandmother From A Hunter Gathering Tribe Become A Solar Engineer?

We’re all looking for stories of hope – that the world can be changed, that we are not limited by our culture, our backgrounds, our histories – and few stories are as inspirational as that of Lucy Naipanoi, a grandmother of Maasai, one of the last hunter gatherer tribes left on the planet. With the …

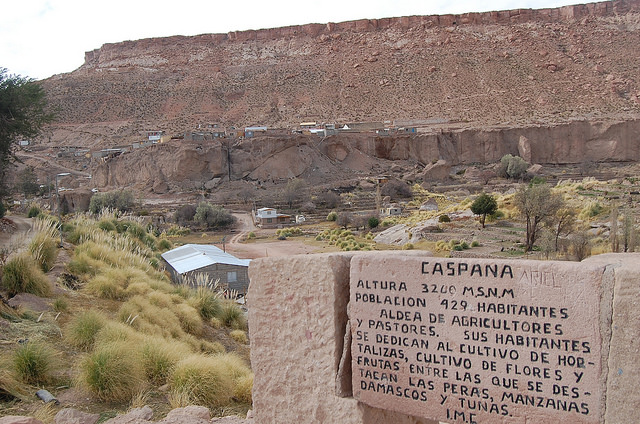

Two Indigenous Solar Engineers Changed Their Village in Chile

Liliana and Luisa Terán, two indigenous women from northern Chile who travelled to India for training in installing solar panels, have not only changed their own future but that of Caspana, their remote village nestled in a stunning valley in the Atacama desert.

“It was hard for people to accept what we learned in India,” Liliana Terán told IPS. “At first they rejected it, because we’re women. But they gradually got excited about, and now they respect us.”

Her cousin, Luisa, said that before they travelled to Asia, there were more than 200 people interested in solar energy in the village. But when they found out that it was Liliana and Luisa who would install and maintain the solar panels and batteries, the list of people plunged to 30.

“In this village there is a council of elders that makes the decisions. It’s a group which I will never belong to,” said Luisa, with a sigh that reflected that her decision to never join them guarantees her freedom.

Luisa, 43, practices sports and is a single mother of an adopted daughter. She has a small farm and is a craftswoman, making replicas of rock paintings. After graduating from secondary school in Calama, the capital of the municipality, 85 km from her village, she took several courses, including a few in pedagogy.

Liliana, 45, is a married mother of four and a grandmother of four. She works on her family farm and cleans the village shelter. She also completed secondary school and has taken courses on tourism because she believes it is an activity complementary to agriculture that will help stanch the exodus of people from the village.

But these soft-spoken indigenous women with skin weathered from the desert sun and a life of sacrifice are in charge of giving Caspana at least part of the energy autonomy that the village needs in order to survive.

Caspana – meaning “children of the hollow” in the Kunza tongue, which disappeared in the late 19th century – is located 3,300 metres above sea level in the El Alto Loa valley. It officially has 400 inhabitants, although only 150 of them are here all week, while the others return on the weekends, Luisa explained.

They belong to the Atacameño people, also known as Atacama, Kunza or Apatama, who today live in northern Chile and northwest Argentina.

“Every year, around 10 families leave Caspana, mainly so their children can study or so that young people can get jobs,” she said.

Up to 2013, the village only had one electric generator that gave each household two and a half hours of power in the evening. When the generator broke down, a frequent occurrence, the village went dark.

Today the generator is only a back-up system for the 127 houses that have an autonomous supply of three hours a day of electricity, thanks to the solar panels installed by the two cousins.

Each home has a 12 volt solar panel, a 12 volt battery, a four amp LED lamp, and an eight amp control box.

The equipment was donated in March 2013 by the Italian company Enel Green Power. It was also responsible, along with the National Women’s Service (SERNAM) and the Energy Ministry’s regional office, for the training received by the two women at the Barefoot College in India.

On its website, the Barefoot College describes itself as “a non-governmental organisation that has been providing basic services and solutions to problems in rural communities for more than 40 years, with the objective of making them self-sufficient and sustainable.”

So far, 700 women from 49 countries of Asia, Africa and Latin America – as well as thousands of women from India – have taken the course to become “Barefoot solar engineers”.

They are responsible for the installation, repair and maintenance of solar panels in their villages for a minimum of five years. Another task they assume is to open a rural electronics workshop, where they keep the spare parts they need and make repairs, and which operates as a mini power plant with a potential of 320 watts per hour.

In March 2012 the two cousins travelled to the village of Tilonia in the northwest Indian state of Rajasthan, where the Barefoot College is located.

They did not go alone. Travelling with them were Elena Achú and Elvira Urrelo, who belong to the Quechua indigenous community, and Nicolasa Yufla, an Aymara Indian. They all live in other villages of the Atacama desert, in the northern Chilean region of Antofagasta.

“We saw an ad that said they were looking for women between the ages of 35 and 40 to receive training in India. I was really interested, but when they told me it was for six months, I hesitated. That was a long time to be away from my family!” Luisa said.

Encouraged by her sister, who took care of her daughter, she decided to undertake the journey, but without telling anyone what she was going to do.

The conditions they found in Tilonia were not what they had been led to expect, they said. They slept on thin mattresses on hard wooden beds, the bedrooms were full of bugs, they couldn’t heat water to wash themselves, and the food was completely different from what they were used to.

“I knew what I was getting into, but it took me three months anyway to adapt, mainly to the food and the intense heat,” she said.

She remembered, laughing, that she had stomach problems much of the time. “It was too much fried food,” she said. “I lost a lot of weight because for the entire six months I basically only ate rice.”

Looking at Liliana, she burst into laughter, saying “She also only ate rice, but she put on weight!”

Liliana said that when she got back to Chile her family welcomed her with an ‘asado’ (barbecue), ’empanadas’ (meat and vegetable patties or pies) and ‘sopaipillas’ (fried pockets of dough).

“But I only wanted to sit down and eat ‘cazuela’ (traditional stew made with meat, potatoes and pumpkin) and steak,” she said.

On their return, they both began to implement what they had learned. Charging a small sum of 45 dollars, they installed the solar panel kit in homes in the village, which are made of stone with mud roofs.

The community now pays them some 75 dollars each a month for maintenance, every two months, of the 127 panels that they have installed in the village.

“We take this seriously,” said Luisa. “For example, we asked Enel not to just give us the most basic materials, but to provide us with everything necessary for proper installation.”

“Some of the batteries were bad, more than 10 of them, and we asked them to change them. But they said no, that that was the extent of their involvement in this,” she said. The company made them sign a document stating that their working agreement was completed.

“So now there are over 40 homes waiting for solar power,” she added. “We wanted to increase the capacity of the batteries, so the panels could be used to power a refrigerator, for example. But the most urgent thing now is to install panels in the 40 homes that still need them.”

But, she said, there are people in this village who cannot afford to buy a solar kit, which means they will have to be donations.

Despite the challenges, they say they are happy, that they now know they play an important role in the village. And they say that despite the difficulties, and the extreme poverty they saw in India, they would do it again.

“I’m really satisfied and content, people appreciate us, they appreciate what we do,” said Liliana.

“Many of the elders had to see the first panel installed before they were convinced that this worked, that it can help us and that it was worth it. And today you can see the results: there’s a waiting list,” she added.

Luisa believes that she and her cousin have helped changed the way people see women in Caspana, because the “patriarchs” of the council of elders themselves have admitted that few men would have dared to travel so far to learn something to help the community. “We helped somewhat to boost respect for women,” she said.

And after seeing their work, the local government of Calama, the municipality of which Caspana forms a part, responded to their request for support in installing solar panels to provide public lighting, and now the basic public services, such as the health post, have solar energy.

“When I’m painting, sometimes a neighbour comes to sit with me. And after a while, they ask me about our trip. And I relive it, I tell them all about it. I know this experience will stay with me for the rest of my life,” said Luisa.

This reporting series was conceived in collaboration with Ecosocialist Horizons. Edited by Estrella Gutiérrez/Translated by Stephanie Wildes

Sturdy Solidwool furniture is formed from wool and bio-resins

We’re mostly familiar with wool as a material for sweaters and socks (or perhaps for eco-friendly biobricks), but English designers Hannah and Justin Floyd of Solidwool are transforming this soft material by combining it with bio-resins, and turning locally sourced wool into sturdy, handcrafted furniture.

© Solidwool

© Solidwool © Solidwool

© Solidwool © Solidwool

© Solidwool  © Artifact Uprising

© Artifact Uprising © Blok Knives

© Blok Knives © Fan Optics

© Fan Optics  © Solidwool

© Solidwool © Solidwool

© Solidwool © Solidwool

© Solidwool  © Solidwool

© Solidwool

The Floyds’ intention was to revive their hometown of Buckfastleigh, which has been traditionally known for its production of wool. Their product, Solidwool, is meant to be an alternative to injection-moulded plastics and fibreglass, by using wool as the reinforcing material, and bio-resins as the binder. They use the fleeces of a particular, local breed of sheep, the Herdwick, which were once widely used by the UK carpet industry. However, demand has declined so far that this “wiry, dark and hard” wool has been unfortunately devalued, but the duo hope to change that by finding new ways to utilize and sustain the local sheep-based economy:

This wool is something special, but along the way, something has gone wrong and its perceived value has been lost. It is currently one of the lowest value wools in the UK. Once this wool was a major part of a shepherd’s income. Now the wool from one sheep sells for around 40p. But we see a beauty in this natural material and want to help see its value increase. The Herdwick flock and their shepherds are custodians of their wild landscape. We want to help them stay that way.

Working with bio-resins and wool in the past few years, the pair have come up with a composite material that they believe is a viable alternative to petrochemically based plastics found in a lot of mass-made furnishings. With a bio-based renewable content of about 30 percent, the bio-resins are diverted from the waste-streams of other manufacturing processes like wood pulping and bio-fuel production, meaning carbon emissions are halved compared to conventional resin production and no resources are diverted from agricultural crops.

Solidwool isn’t just for the chairs and tables seen in their Hembury collection; it could be used for any product like eyeglasses and knife handles. According to Design Milk, the Floyds are collaborating with other companies like Blok Knives, Artifact Uprising and Fan Optics to use Solidwool in their products.

We are liking how wool is used in a surprising and new way here to create durable and eco-friendly furniture and accessories, beyond the conventional fashion. You can see more or shop around over at Solidwool.

Please enable JavaScript to view the comments.

The Axiom House is a flatpack prefab net-zero “game-changing concept home”

Being an architect can be so frustrating; the established ways are so entrenched, residential building technology is so primitive, it’s all done by hand in the field where the biggest innovation in thirty years was the nail gun replacing the hammer. Meanwhile in the architects offices there are tools that we never dreamed of thirty years ago- computers instead of drafting boards, 3D renderings that spring our of our drawings like magic, and perhaps most importantly of all, the Internet that changes how architects can market what they do.

That’s why the Axiom House, being developed in Kansas City by Acre Designs, is so interesting. Jennifer Dickson is an architect; Andrew Dickson is an industrial designer; together they are trying to turn a house into an industrial product that can be delivered anywhere in a shipping container, for a price that is competitive with conventional construction. They are not thinking like designers, but like a tech startup:

Acre is the very definition of a technology company. We apply scientific knowledge from the fields of architecture, engineering, environmental design, and material and construction science in the most practical way imaginable. We’ve used these practices to create homes that take half the time to build, use a fraction of the resources, and have as little as half the lifetime cost of traditional homes.

The house itself is a flexible 1800 square feet, designed to adapt to its occupants’ life cycles. It’s described as Net Zero energy, producing as much energy as it consumes; it achieves this by being built to near passive house standards so that very little energy is required to operate it in the first place. As they note,

Our homes are 90% more efficient than standard construction to begin with, and we make up the difference with a small solar panel (PV) array. We start with an efficient floor plan and a tight building envelope to prevent air from getting in or out. We use high-efficiency doors, windows, and appliances, take advantage of natural (passive) heating from the sun, and utilize unique heating and cooling solutions.

© Acre

© Acre

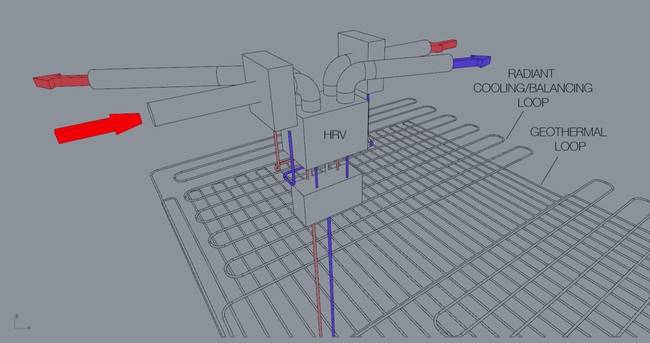

The heating and cooling system is indeed unique; I had to ask for an explanation. In the early days of Passive Houses, many had what are called Earth Tubes, or big pipes buried in the ground that were used as ducts to pre-cool or pre-warm air to the ground temperature, which is about 55°F in Kansas City. But earth tubes proved hugely problematic, delivering condensation, mold, radon and other wonderful things as well as air. Instead, the Axiom house has what they call Passive Geothermal, (PGX) a riff on what others have called brine loops or glycol ground loops. There is a grid of pipes buried in the ground which deliver water at near 55°F to a heat exchanger built into the Heat Recovery Ventilator (HRV) that is required in a house that is so tight. So one gets all the benefits of an earth tube, preheating or precooling the air, without the problems and at a lot lower cost than a fancy ground source heat pump. They appear to work well; in an article by Martin Holladay in Green Building Advisor, a passive house builder called them “amazingly effective.” However Martin, always the skeptic, writes:

Of course, just because a ground loop works, doesn’t mean the system is cost-effective. Many energy experts have speculated that the pump needed to circulate the glycol solution uses almost as much energy as the system collects. The results of one monitoring study indicate that these experts may be right; data gathered in Vermont suggest that the simple payback period for this type of system may be as much as 4,400 years.

© Acre

© Acre

They are also delivering the tempered water to the radiant floor, and and addition to this system, the house also has a mini-split air source heat pump. Given the near- passive house amount of insulation, tight construction and careful siting, I suspect it won’t get a lot of use.

© Acre

© Acre

The structure is a flatpack of SIPs, or structural insulated panels. These are a sandwich panel of plywood or OSB board and expanded polystyrene insulation, 10″ thick for the roof and 8″ for the walls. They claim that that it can be built at prices competitive with other houses in Kansas City, running now at $110 to $135 per square foot. How do they do it?

It’s not any one thing, but a combination of strategies, that allows us to achieve this. A few examples:

By offering fixed plans, we can build hours of engineering and design into the base cost of the home. Just like with your car or phone, focused product development helps us deliver a refined, high-performance home that can be repeated again and again. Starting with a right-sized, efficient floor plan has a domino effect: reducing up-front costs, energy demands and system sizes throughout the house. With a lighter load, we can eliminate ductwork, wiring, plumbing runs, and the expensive labor associated with these. With streamlined, repeatable construction, we shave months of labor costs out of each job.

© Acre

© Acre

Jennifer Dickson tells Metropolis:

We see no reason why architect-designed, highly efficient housing should not be attainable at a reasonable price point. To do that, we are treating this more like a car than a house. With cars, the design effort goes in at the front end, and at the purchase end, the customers do not get a custom product, but they get access to high-end finishes and their choice of features. We think we can leverage buying power by providing a set of well-designed packages.

Having used these same arguments for a decade when I was working in prefab, I am a bit skeptical that they can do that. I found again and again that designs are rarely repeatable, everyone wants to customize, and that customers don’t care about right-sizing, they care about price per square foot. And it’s just so hard to compete with conventional construction, the guy in a pickup with a magnetic sign and a nail gun.

But it is so exciting to see architects and designers trying to innovate in the design of homes and the way that their services and the product are delivered. I am really rooting for them and hope it works. Read more on the website and like any startup looking for money, attention and validation, they are crowdsourcing on Indiegogo.

Please enable JavaScript to view the comments.

The Vietnamese University that Plants Paradise Where There Could Be a Parking Lot

Verdant lawns and shady groves of trees lining the quad-that kind of landscaping is common on America’s college campuses. But once construction on FTP University’s new campus in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, is completed, the city’s 8 million residents might have a tough time figuring out where the buildings start and the greenery ends.

The private, technology-focused institution has commissioned Vo Trong Nghia Architects, a Vietnamese firm that specializes in green architecture, to build a 14-square-mile campus. Plans for the campus include terraced buildings tricked out with tree-covered rooftops and balconies, as well as courtyards filled with plants. The images resemble pyramids rising out of the jungle.

RELATED: Why a Puddle-Friendly Preschool Could Be the Key to Kids’ Success

“To engage the city in a different way, FPT University appears as an undulating forested mountain growing out of the city of concrete and brick. This form creates more greenery than is destroyed, counteracting environmental stress and providing the city with a new icon for sustainability,” the architects said in a statement. “Environmental stress is observable through frequent energy shortages, increased pollution, rising temperatures, and reduced greenery,” they continued.

Thanks to development and industrial construction, 60 percent of forested areas in the Southeast Asian country have been destroyed, according to a 2011 report from the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development. “Ho Chi Minh City illustrates these issues, having only 0.25 percent of the entire city covered in greenery,” according to the architect’s statement.

“Cities, especially in thriving countries like Vietnam, are growing at such a speed that infrastructure is unable to keep pace,” added the architects. The deforestation-fighting concept certainly resembles a tropical paradise. It’s unclear when the firm expects to complete the project.

How Permaculture Can Restore Ecosystems & Communities

In the rural Shona African community in Zimbabwe, five villages of 7,000 people have joined together to form the Chikukwa Project, named after their local chief. Twenty years ago their land was deforested, barren, and nothing would grow there in the summer months. When the rains came, they washed down the slopes taking the soil with them. The springs had dried up and the people were poor, hungry, and suffering from malnutrition.

The Shona decided to do something about it and sought advice from permaculture pioneer, John Wilson. Slowly, a field at a time, they built water retaining landscapes: terracing the slopes and digging swales to hold the water in the soil. They added composted manure to these terrace beds to build soil and grow food. They stopped grazing animals and foraging for firewood in the gullies where the springs rose and planted native trees there to hold the moisture in the soil. They also stopped untethered grazing of goats on the hillsides, allowing trees to regenerate, and they started driving their cattle to agreed grazing areas. They learnt new skills: specifically permaculture training, conflict resolution, women’s empowerment, primary education and HIV management.

Within three years, the springs began to reactivate. They saw that the yields from the plots with swales were bigger than the plots without them. Twenty years later, where there was once eroded soil and over-grazed slopes, there are now reforested gullies with flowing water, terraces full of vegetables, grains and fruit, and high ridges lined with trees for firewood. In the villages, there are home gardens, pens for hens and goats, water tanks to catch rainfall runoff, and a culture of cooperation that values people skills as much as horticultural techniques. The landscape is verdant and biodiverse, and the gardens and farms produce crops for the families and for market, bringing an economic yield back into the region. All this in one generation.

Gillian and Terrence Leahy, film makers, were invited to make a film about this transformation at Chikukwa. They saw how these Shona Africans had pulled themselves out of hunger and malnutrition, using permaculture farming techniques and bottom-up social organisation. They understood that this could be replicated anywhere in the world.

The Loess Plateau in China, an area the size of France, was similarly regenerated using water retention landscapes. This was documented by John Liu in his incredible film, Green Gold. There are many more stories from all over the world where permaculture and other regenerative techniques have been applied to barren lands. Earth restoration is not only possible, it is already happening. We need to build capacity and find ways to take this work wherever it is needed, helping people to lift themselves out of poverty and rebuild broken communities. John calls this ‘the great work of our time’, work that not only restores whole ecosystems but also brings dignity and wellbeing to our fellow human beings. Nelson Mandela said, “Overcoming poverty is not a task of charity, it is an act of Justice. Like slavery and apartheid, poverty is not natural. It is man made and can be overcome and eradicated by the actions of human beings. Sometimes it falls on a generation to be great. You can be that generation. Let greatness blossom.”

It is perhaps easier to regenerate rural landscapes where the vestiges of a traditional culture retains gardening and farming skills, but it can happen in post-industrial wastelands too. I have been following permaculture teacher, Sarah Pugh, as she travels through the urban American landscape, researching urban permaculture projects. Sarah lives in Bristol, UK and works with permaculture and transition there. She set up Shift Bristol, a training project that takes people through a year of learning practical permaculture. Sarah wanted, however, to reach beyond her own city and see for herself what urban regeneration looks like in places like Detroit, Chicago and San Francisco where the extremes of wealth and poverty are keenly experienced. She visited Detroit and she observed, “So much space, so much energy, so many problems … so much potential. The population of Brightmoor [a local neighborhood] has dropped from 20,000 to less than 10,000. 70,000 empty, burned out and rotting houses in Detroit. Community gardening in full swing here…”

Sarah leaves a trail of hope on social media as she travels. It is such a different story from the usual diet of pet videos, celebrity gossip and the haunting escalation of our global problems. We hear too much of the dark side in all medias, and too little of the solutions. I am convinced that it makes people turn away and disengage, feeling that our futures are hopelessly predetermined. This magazine is different. It is full of stories of hope, and we hope you not only enjoy it, but are inspired.

To learn more about this project and see the film, visit:

See the film at: www.permaculture.co.uk/videos/green-gold-how-can-we-regenerate-large-scale-damaged-ecosystems

Further resources

Watch: Inhabit – Regenerating city & farm landscapes

Regenerating barren landscapes: Mexico

Watch: Green Gold – how can we regenerate large-scale damaged ecosystems?

NEW ENHANCED

NEW ENHANCED

PERMACULTURE SUBSCRIPTION

Exclusive content and FREE digital access to over 20 years of back issues

SUBSCRIBE:

www.permaculture.co.uk/Subscribe

Results Driven Land-Use Planning – Spacing National

In North America, cities are increasingly burdened with a growing list of required infrastructure maintenance and replacements. With few options for generating tax revenue, these obligations are stretching municipal budgets thin, leading to uncertain and lengthy conversations with higher levels of government about funding. This process delays the critical infrastructure upgrades that we need today rather than tomorrow.

Rather than seeking ways to maximize the return on existing infrastructure, North America is obsessed with building newer and bigger infrastructure, which does not match current demand. According to Strong Towns, this new-infrastructure fetish is literally bankrupting our cities. For example, in Vancouver, Canada the B.C. Liberal provincial government has replaced the Port Mann bridge with one of the world’s largest bridges, based on impractical automobile growth predictions. The bridge has consistently fallen short of the predicted traffic projections and its debt continues to grow with little or no returns on billions of public dollars. The B.C. Liberal provincial government is in the midst of repeating the same mistake again by replacing the George Massey tunnel with an overbuilt and overcapacity billion dollar bridge that will never be able to pay for itself.

This approach to development can be seen in many cities across North America and fails to deliver the results we need today. In many cases, cities opt for expensive and grand projects that take years to reach fruition. So what’s the alternative? At Slow Streets, we believe that Amsterdam provides a great development model that delivers short-term results efficiently and effectively. This article provides a quick case study of the Amsterdam approach to development.

Lay the Bones for Complete Neighbourhoods to Achieve Results-Driven City Building

Clearly the best solution is to prevent overbuilding infrastructure from the start. This is where Amsterdam comes in. Amsterdam often plans its new neighborhoods and infrastructure requirements to match existing demand. In North America, cities often build the residential uses first and then eventually build community amenities and commercial uses. This is an absurd way to build our urban landscapes, as incomplete neighbourhoods force residents to commute elsewhere in the city. This also places an unnecessary, unpredictable strain on already overburdened public services like roads and schools. Parents often move into these new neighborhoods with the promise of playgrounds, schools, or community centres that never come.

Amsterdam has understood this, so when the demand for more housing or public services requires them to revitalize an existing neighborhood or build a new one, they will often ensure there is transit route servicing the area first. While it may seem to make little sense to provide transit to nowhere, it ensures that the bones are in place to support a healthy and complete neighborhood right from the start. Thinking about transit right away will help ensure successful transit geometries. Reliable transit services will minimize the need for automobiles and the associated congestion, pollution, and dangers to our children and family members they bring.

Next, the city will usually then proceed to invest in a public facility such as a library, community centre, museum or school. This will serve two purposes: first it will ensure that the new public service amenity will closely match pent up demand, relieving pressure from other overcapacity public services. Secondly, it will create predictable demands in the area and spur spill-over demands such as a coffee shop, a neighborhood drinking hole or other commercial uses. Based on the demand that grows around the public amenity, the government can then more accurately gauge the need for other public services in the area and incrementally build out the appropriate mix of residential and commercial uses.

Taking the demand based public service amenity city building approach ensures that we closely match the infrastructure demands with residential requirements like schools, transportation and public services. As a result, one maximizes the return on investment from public dollars. Furthermore, one avoids overbuilding too much infrastructure that is not operating at an efficient capacity and minimize the need for more taxes. While this approach will take significant leadership and cohesive civic staff culture, Amsterdam provides several other examples for short-term urban land use corrections to meet unfulfilled demands now.

Adaptive Reuse

In terms of balancing the infrastructure deficit, the best solution is often the one that is already built. In Canada, our heritage buildings are treated with little value. For example, in Edmonton several of the historic buildings and infrastructure built in the growth boom of the early 1900’s – such as the Rossdale Power Plant, the Walterdale Bridge or the McDougall United Church – are requiring repairs. Incredulously, the conversations often results in demolition.

While these 100 year old buildings may no longer be able to serve their original purpose, they were built in a time when things were built to last (as proven by their existence still today). Modern buildings today are often only built to last twenty years. Therefore, it is in our best interest to set aside a little bit of maintenance funding and to be flexible with tolerated uses within these precious historic buildings. These buildings not only create economic value for the surrounding area, but create cultural value by connecting us to our shared past. Additionally, as community landmarks, they play a critical role in wayfinding and creating a sense of place.

Amsterdam has examples of this creative reuse of infrastructure in spades: whether it is a radio tower rig converted into a restaurant, a former industrial crane converted into a hot-tub, an old water tower converted into a flexible development show room, a tram storage facility converted into a shopping and food court facility, warehouses converted into bars or event centres, oil tanks or historic storage buildings are converted into community centres….the list goes on. Amsterdam understands the savings and value generation for the public that come from maintaining and repurposing historic infrastructure.

Part of the reason for this prolific reuse of infrastructure is mixed-use zoning which establishes the tools needed right from the start, in order to ensure that a neighbourhood is complete. The Amsterdam planning department does not blindly follow rigid guidelines dictating what uses can go where. Rather they use sound, case-by-case judgment to determine whether specific land uses are appropriate in relation to their context. However, as a rule, one notices that the repurposing of structures ensures that the new buildings meet a high level of architectural standard. This is critical for ensuring that the building creates value in its context.

If the cost is prohibitive to reuse a building in a specific way, first try to change the regulations. If that fails, find a more cost effective way to use the building. Even if the municipality donates the space for free (more on this later), this can serve to generate more value from new business taxes or the public life new inhabitants create. In the end, the reuse of historic buildings serves to create an interesting, adaptable and resilient city. I mean, a hot-tub at the top of a crane, how cool is that?

Lighter, Quicker, Cost Effective

Finally, we need the flexibility to build critical infrastructure now, not two to three years from now. Often, our current regulations structure delay the building of the critical infrastructure that we need today. At Slow Streets, we believe that we should change them or treat them more as guidelines. Common sense should prevail before requiring lengthy and capital intensive studies or reviews. Often any solution is better than waiting years for the funding of the perfect solution. Not only can light, quick and temporary solutions be built to the high standards of permanent solutions, but they can also be adapted easier.

To demonstrate: What if more office space or student housing is required now and capital is scarce? In Amsterdam they would build temporary, but attractive housing using recycled shipping containers, until funding can be acquired to replace them with brick and mortar residences.

Another example is the NDSM – an artist work centre inhabiting a repurposed, abandoned ship building warehouse. To quickly build working quarters, the City opted to reuse shipping containers. The result is a vibrant, multipurpose and dynamic space for people to experiment with art and other entrepreneurial endeavors.

In another case, there was an empty industrial land that the city of Amsterdam wanted to convert into an office park called De Ceuvel. The only problem is that the land is contaminated with industrial chemicals. Most municipalities are faced with the choice of expensive excavation and soil replacement or letting the chemicals naturally breakdown (which takes several years). If you live in North America, you can probably recall at least one property – such as a decommissioned gas station – which has sat empty with a cheap chain-link fence around it, serving as an eyesore and contributing little in the way of fostering new businesses or generating tax revenues. In Canada, such properties exist ironically on some of the most productive properties on popular retail streets such as Whyte Avenue in Edmonton or Denman Street in Vancouver.

Amsterdam decided to go with the latter letting the chemicals breakdown, however they did not want the land to sit empty. As a solution, Amsterdam leased the land commercially at no cost to young entrepreneurs for a period of 10 years. There was still the sticking point of the contaminated ground, but as always, the Dutch are very practical with their solutions.

Dutch regulations require that decommissioned boats must be disposed of properly. This can come at a high cost. The City decided that several of these boats would be diverted from the waste system and be repurposed as offices. Finally, an elevated boardwalk was installed to keep people off the contaminated ground. Nearby a restaurant and bar has been built and, in the end, an interesting office park with a stunning view of Amsterdam and the IJ river is available for budding enterprises (at no cost) while adding to the tax revenues. All of this while cleaning up contaminated land and reusing materials.

Conclusion

In these days of limited municipal budgets and growing infrastructure requirements, it is a blatant abdication of our responsibilities for our cities to not invest in results now. We do not need the perfect solution, we need something that will maximize benefits for today until a suitable replacement can be made. Ensuring that we start new neighbourhoods with the necessary tools and public amenities to create a healthy and complete community, will ensure that cities can recapture the value created from public investments. Utilizing our existing stock of infrastructure more efficiently will save all of us money down the line, and at the same time, generate more economic and community value. Finally, changing our government structure and culture will payoff in spades down the road by better matching the infrastructure demands with the citizen requirements.

***

Slow Streets is a Vancouver based Urban Design and Planning

group providing original evidence for people oriented streets.

Vertical Hydroponic Farms feeding urban communities.

Dickson Despomier,

a proponent of urban vertical hydroponic gardens, poses the problem as such:

By the year 2050, nearly 80% of the earth’s population will reside in urban centers. Applying the most conservative estimates to current demographic trends, the human population will increase by about 3 billion people during the interim. An estimated 109 hectares of new land (about 20% more land than is represented by the country of Brazil) will be needed to grow enough food to feed them, if traditional farming practices continue as they are practiced today. At present, throughout the world, over 80% of the land that is suitable for raising crops is in use (sources: FAO and NASA). (1)

The current centralized system of agriculture creates a significant negative effect on worldwide carbon emissions. Urban cities with densely populated areas are a prime example, given their lack of land available conversely need for imported foods. According to John Hendrickson of the Center for Integrated Agricultural Systems, fresh produce in the United States traveled an estimated 1,500 miles (2). Urban Vertical Hydroponic Farms (VHF) can change that.

One of the challenges with urban farming is access to sufficient affordable land. In a growing number of urban centres (e.g. Vancouver), by transforming vacant commercial or industrial land into a farm the property owner receives a tax break on their property taxes of 40-60 percent (3). By employing VHF technology the farm can achieve yields of 3+ times that of traditional soil gardening (6).

We propose that communities across North America transform vacant land and existing gardens in their neighbourhoods to high density outdoor vertical hydroponic farms (VHF) by using a non profit association with the following goals:

- Provide a source of fresh local healthy food to their community

- Increase a community’s capacity to grow their own food

- Reduce a community’s carbon footprint

- Create jobs with living wages for marginalized people in communities

What actions do you propose?

Feasibility

It is estimated that for every kilogram of beef, 15.23 kg of CO2 greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are produced (4). A kg of produce transported in the current agricultural farm system produces approximately 2.6 CO2 kg GHG emissions. Those carbon emissions are produced during the transportation of foods from farms to tables assuming an average 2,500 km traveling distance (5). Urban VHFs have the potential of reducing those carbon emissions by: encouraging less meat consumption, recycling nutrient rich water using minimal electricity (a 290-396 GPH 28 watt pump using up to 90% less water than alternative farming) and decentralizing distribution from urban VHFs located on vacant land in high density population areas.

The pictures used in this proposal were taken over the course of three years, by a group called Green Guys on the Drive (6), located in Vancouver, British Columbia who currently operate East Vancouver’s only community supported hydroponic urban vegetable farm. They have 11 CSA members who each pay $200 at the start of the season to receive their share of the farm’s weekly harvest which is sufficient for 2 people. They currently have one farm tended to by three co-founders, Brandon, Win and Dan. The farm consists of three VHF units with a total capacity of 320 plants and a footprint of 34 ft2. This works out to a density of 9.4 plants/ft2 which is more than 3 times the density of traditional soil based planting for lettuce (a leafy green) (7). Green Guys on the Drive produce on average 15 lbs of produce every week beginning with the first harvest in May and the last at the end of October (seedlings are started in March and transplanted into the VHFs in early April and throughout the growing season) Some examples of variety include lettuce, spinach, kale, pac choi, basil, and mustard. Green Guys on the Drive is non profit and all labor is volunteered from the founders and the community. Membership fees are used to pay for the capital costs of each VHF and the operating costs (nutrients, electricity etc…).

The efficiency of being able to stack plants vertically per square foot of ground is multiplied 3-10 times – depending on how high one can safely farm in their backyard and the particular setup. This is a crucial advantage of vertical farming to conventional backyard gardens. Green Guys on the Drive has demonstrated that a single farm can have an impact on a local community’s carbon footprint by reducing meat intake (presumably since vegetables are readily available and pre’paid’) and carbon costs of food production and transportation. The problem then, is how to build, grow and maintain numerous communities, with farms as hubs, within a city that utilizes VHF’s to further reduce carbon emissions.

Vertical hydroponic farms are gaining interest around the globe as business models are being tested to prove profitability. However, research is primarily being done in large-scale indoor facilities that can operate year round, as is the case in one of the first industrial applications of vertical farming at the Paignton Zoo Environmental Park in the United Kingdom. Vertical farming in backyards has also been done on small scale hobby farms numerous websites and Youtube instructional videos creating a niche community.

Green Guys on the Drive hope to serve as a catalyst to help communities across North America to increase their capacity to grow their own food while reducing their carbon footprint by transforming vacant land in their communities into high density outdoor VHFs. Green Guys will accomplish this by establishing multiple successful urban farms within the Greater Vancouver area and then use the revenues to create an online knowledge centre (perhaps partnering with openAG) to help communities across North America to do the same.

Getting Started

In the first year Green Guys will establish a pilot urban farm within Vancouver employing similar technology to what they use now only at a larger scale. This will allow Green Guys to refine the process and business process for growing at scale and whose successful operation will help acquire additional funds through grants and land to then construct a full scale urban farm.

In the second and third years of operation Green Guys would establish multiple urban farms within the Vancouver area in high density population centres and/or high traffic locations. This would allow the Green Guys to sell directly to community members on their way to and from work. In subsequent years Green Guys will utilize the proceeds from their established urban farms to create an online knowledge centre whereby interested communities can learn how to grow their own fresh local food while reducing their community’s carbon footprint.

Gathering Interest

Gathering Interest

The target audience of this campaign will be people who understand the immediacy of global warming. We would contend that that audience consists of scientists, engineers, climatologists, and more generally, academics. If this project were presented to MIT faculty and students, hopefully they would be interested in sharing knowledge and participating in a a pilot urban farm in 2016; perhaps in association with MIT CityFARM and/or OpenAG. The Center for Sustainable Food Systems located at UBC Farm is another possible partner located close to the Green Guys’ existing garden. A larger variety of contributors would allow for greater open source knowledge available to volunteers. For example, an engineer might be able to maximize harvests by advising the front line volunteers/employees how to best grow their vegetables in their unique climate, situation, and backyard or rooftop.

Goal of First Year

The goal of this first year is to construct a pilot farm in the Vancouver area. More specifically the Green Guys will:

- Leverage results from current urban CSA farm to secure grants from the City of Vancouver and the Vancouver Foundation to fund pilot farm and to build large scale urban farm during second year.

- Partner with the University of BC to have a masters student conduct a field study/research project on the farm (UBC gets research data, Green Guys gets someone to operate the farm for free.)

- Build relationships with interested organizations (Vancouver Urban Farming Society, Vancouver Farmer’s Markets, UBC Outdoor farms, City of Vancouver, etc).

September – December 2015

During these months the design for the pilot farm would be created that would incorporate as much as possible the current VHF CSA’s existing infrastructure. This would then be used to develop a detailed operating plan and budget. Given the pilot farm would produce enough produce on a weekly basis to feed more than 50 people the produce would be sold at local farmers markets. Any additional funds required to build or operate the farm would be acquired through applying for grants from the City of Vancouver and the Vancouver Foundation.

A partnership would be established with the Sustainable Food Systems at UBC Farm through which Green Guys on the Drive would get access to free and/or subsidized labour to operate the pilot farm and UBC would get data on a sustainable food system.

January – February 2016

The focus of these months would be the construction of the pilot farm and establishing retail space at local farmers markets through which to sell the produce. Seedlings would be started in the green house mid February to be ready for harvest at the start of May.

Possibilities for Expansion

Possibilities for Expansion

Thus far this proposal has focused on shifting the agricultural system of Vancouver, BC from imported to local neighborhood sources. The early years would focus on developing a VHF model for independent groups or organizations to emulate in other neighborhoods, cities, or countries on a small (as in the case of a backyard garden) or large (as in the case of an vacant gas station lot) scale urban farms. However, to enact the greatest impact possible we must draw on diverse resources and existing infrastructures that are unified by the same goal of decentralizing the agricultural system in urban areas.

Update: Since the creation of this proposal, the Green Guys on the Drive have begun discussions for the retrofitting of a rooftop garden at their local YWCA to incorporate a VHF unit. The goals would be to improve the community’s capacity to grow their own local vegetables, provide fresh greens and herbs to local families in need, and reduce the carbon footprint of the community.

The inclusion of an apartment building rooftop in the first year could serve many purposes. First, it is a space often used for aesthetic purposes and contains vegetation but rarely for the purpose of feeding residents and very rarely using such an efficient setup as VHFs. Second, by giving a VHF to an apartment building free or at cost as a test case, we can test the feasibility of this system to grow vegetables in the place that needs it most; densely populated city centers. In the case of the YWCA, fresh herbs and vegetables can be given to the needy at a minimal cost and impact to the environment.

If the end goal is to enact large scale change to the existing agricultural infrastructure, cooperating with other organizations with similar goals is crucial to having a focused, unified approach to improving climate change. As experience is gained in the early years creating efficient VHFs, the Green Guys hope to collaborate with many local gardens/farms to do the same upgrading their conventional soil based gardening.

A decentralized and diversely sourced agricultural system such as this proposal would require a robust web solution to connect farmers to consumers, potential farmers to resources (i.e. knowledge centre), and investors to farmers. Fostering an online, inclusive, community-driven culture could potentially be a large factor in expanding internationally. It would also allow consumers to find the closest farm, farm market, or community garden from which to participate or purchase fresh vegetables from. In association with programs like openAG, the Green Guys on the Drive will also contribute to learning materials, an open source urban farming knowledge centre, and simplifying construction/maintenance of VHFs in an attempt to lower the barriers to urban farming.

Who will take these actions?

Green Guys on the Drive will provide the experience and help plan, build, and farm.

Volunteers will help build, operate, and maintain the VHFs, and offer various skills

CSA members will support climate change by purchasing shares in each season’s harvest

Professors and graduate students will provide knowledge, input, and research

Where will these actions be taken?

Initially these actions will begin in local gardens located in Vancouver with enough volunteers to ensure farms can operate through the spring, summer, and fall. However, the scalability of this project lies in each community’s ability to operate independently of other communities once the basic knowledge for maintenance is met. This is an excellent opportunity for open source agricultural projects like OpenAG to serve as a knowledge base to amateur/novice volunteers. The goal is to sprout as many urban farms as possible, with basic infrastructure laid out to self sustain, in as many densely populated cities as possible across the world.

How much will emissions be reduced or sequestered vs. business as usual levels?

Impact of pilot farm = 740 kg CO2e/year (8)

Impact of urban farm (assuming 8000 square feet or size of vacant gas station) = 33,634 kg CO2e/year

4 urban farms established in Greater Vancouver by 2020 = 132,314 kg CO2e/year

30 urban farms established worldwide using a similar model by 2020 = 1 million+ kg CO2e/year

(8)

What are other key benefits?

Vegetables are relatively cheap for the consumers.

Readily available vegetables will hopefully reduce meat consumption, leading to additional carbon gains.

VHFs use water efficiently; a growing concern in areas faced with drought as a result of global warming.

Encourage community involvement.

Potential to feed homeless if there is excess.

Data can be gathered for future projects and OpenAG.

Knowledge base is established for community members to independently create their own urban VHF.

What are the proposal’s costs?

Construction Costs

The cost to construct the pilot farm that would produce enough produce for fifty people is estimated at $10,000.

Maintenance and Operation Costs

The maintenance and operation costs per season (7 months) plus assuming a labourer 24 hours per week at 20 dollar per hour $14,560.

Total Cost

The total cost for the year would be: $27,560.

Revenue

6 lbs per unit per week at 30 weeks per season and 8 units would produce 655 kg.

At price $30/kg

Revenue = $19,650

Total Funding needed for first year: $7910

Time line

Short Term

The first two years will include the construction of 1 large pilot backyard farm and 1 large-scale farm. 1st year will be run strictly by volunteers (including the Green Guys) for the purposes of market research, building of volunteer base, and recovering investment costs of construction through sold shares. Throughout all stages municipalities, non-profit organizations, universities, and possibly a crowdfunding round will be sought for grants and investments.

Medium Term

Processes will be streamlined and methods documented to assist with ‘opensourcing’ agriculture to urban communities. A web platform will be created to facilitate volunteers connecting and getting involved in other ways.

Long Term

A headquarters will be established at a building or warehouse near downtown Vancouver, to pursue long term growth and a large-scale urban farm in a city center, funded by profits, donations, and grants.

Related proposals

Resilient Agriculture with Hydroponic Carbon Capture (HCC) / gas2green

Suburbia as source of food and regenerator of resources / SU allotment gardens

References

- Dickson Despomier. The Problem. <http://www.verticalfarm.com/>

- John Hendrickson. 1996. Energy Use in the U.S. Food System: a summary of existing research and analysis. <http://www.cias.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2008/07/energyuse.pdf>

- City of Vancouver Business vs. Recreational/Non-profit Tax Rates. Retrieved on July 13, 2015 from: <http://vancouver.ca/home-property-development/business-and-other.aspx><http://vancouver.ca/home-property-development/recreational-and-non-profit.aspx>

- Environmental Working Group. 2011. Meat Eater’s Guide to Climate Change + Health. <http://static.ewg.org/reports/2011/meateaters/pdf/methodology_ewg_meat_eaters_guide_to_health_and_climate_2011.pdf>

- Food Transportation Issues and Reducing Carbon Footprint. Wayne Wakeland, Susan Cholette, and Kumar Venkat. 2012.

- Green Guys on the Drive. Facebook group. <https://www.facebook.com/GreenGuysTheDrive?fref=ts>

- B. Rosie Lerner and Michael N. Dana. Apr 2009. Consumer horticulture, Leafy Greens for the Home Garden. <http://www.hort.purdue.edu/ext/ho-29.pdf >

- Green Guys on the Drive. Table for Carbon Savings of VHF Units. <http://imgur.com/0KztBBM>

34 supporters